The Boy, The Heron, and the Luxury of Feeling Confused

Like this project

Posted Sep 5, 2024

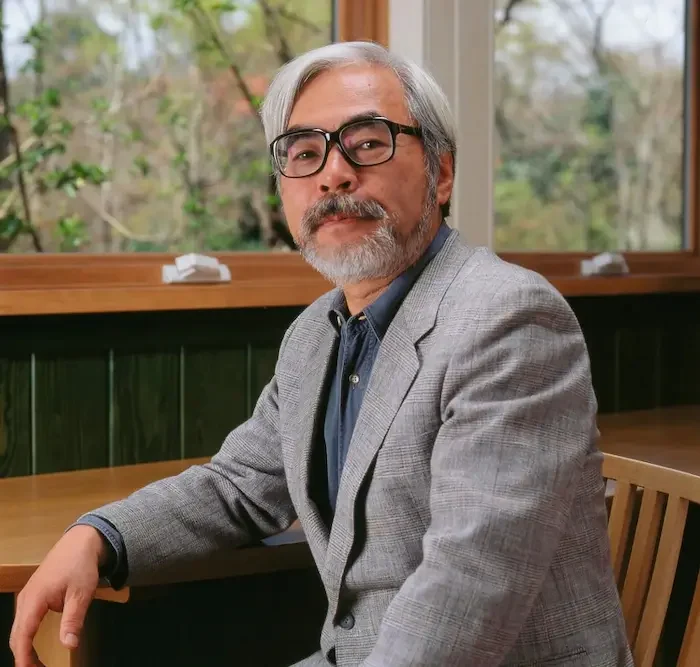

El 19 de febrero, la más reciente obra de Hayao Miyazaki fue galardonada con el premio a mejor película animada en los BAFTA 2024. Ahora, camino a los

Likes

0

Views

11

On February 19, Hayao Miyazaki's latest film was awarded Best Animated Film at the 2024 BAFTAs. Now, heading towards the Oscars and nominated in the same category, The Boy and the Heron stands out as another great film from Studio Ghibli. The unique narrative choices have left more than one viewer lost in what, at first glance, seems like a classic children's story about a journey to an inner world, but contains so much more.

Mahito Maki struggles to leave the past behind as he watches the world around him move forward. He tries to cope with his mother’s death in a fire during the war, while his father has married his deceased wife’s sister, who is now pregnant. Mahito moves to a rural area of Tokyo, starting a new life with a new family that feels foreign to him. There, he discovers an abandoned tower and, with the help of a somber talking heron, enters a fantastical world in search of the promise to see his mother again.

For those familiar with Miyazaki’s previous works, the premise of The Boy and the Heron might seem quite similar to Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, or Howl’s Moving Castle. The director chooses to prioritize the creation of a fictional world as the essence of the film, rather than creating one solely as a vehicle for storytelling. In The Boy and the Heron, the world Mahito explores is as much a character as he is. It is immense, taking its time to form surreal ideas in its beginnings, and ultimately showing an absolute extravagance and complexity that can be overwhelming as the story enters its second act.

Many viewers may find the film overwhelming, even irritating. The Boy and the Heron repeatedly presents fantastical elements, each more creative and strange than the last, with no apparent explanation. The story’s pace does not expect the viewer to fully understand what is happening. But precisely because the film does not demand that of us, we can choose to enjoy the journey. This particular narrative style works well when we are alongside a protagonist as withdrawn as Mahito, who is as lost as we are, and ends up serving as a vehicle for us to traverse the same path.

An explicit explanation of the world in The Boy and the Heron would only contradict the sense of wonder that the story portrays, where curiosity and creativity are rewarded. This results in a constant feeling that what we are seeing is like a bunch of deliberately tangled threads, and there is much beauty in that. These creative decisions are a result of Miyazaki’s direction as a filmmaker, working more freely and purely than ever. This demonstrates a decision-making process motivated by the priority he places on his vision for his work, rather than what might seem structurally logical for the progression of a story. As a result, The Boy and the Heron feels like one of his most personal films.

Another decision Miyazaki makes in directing the film is reflected in his approach to themes of mortality, inheritance, and autonomy. Some of these concepts are clear from the beginning, while others almost seem like a surprise by the end of the film. The idea of death extends beyond Mahito and his mother, reaching the symbolism of observing how something you have created for so long, like love and passion, is destined to end. The reflections with which the film concludes inevitably extrapolate to the author’s position regarding his career, as the eventual end of it. With The Boy and the Heron, we witness Miyazaki’s meditations on his life's work and the future of other works inspired by his own.

The Boy and the Heron may not be the most accessible or the easiest film to digest for a broad audience. It sometimes seems to require a specific attitude to appreciate. But it is not a memorable experience in spite of this; rather, it ends up being Miyazaki’s most sincere and intimate film to date, not to mention one of the most beautifully animated.

Foto: doblaje.fandom.com