Nike Field General 82: Uniform of Manchester's Unsung Force

In present society, motives are so centred by virality that fewer makers find reward in result above gratification, less spurred by the part they play in the innermost workings of their city. But when positioned in a metropolis as culturally badged with working-class industry as Manchester, labouring in its favour is then simply part of the status quo. Punctuated by red brick mills and listed warehouses in tandem, its place in the 19th century textile trade and consequent Cottonopolis namesake has instilled the locale with a steady, grafting mentality: its quiet workers architects of purpose in every abundant sector.

With the turning of the city’s cogs motioned by each trying shift in turn, the jar of their cranking has softened since its manufacturing heyday, eased by northern togetherness, present within its creative scene. A silent spectacle not commonly caught glimpse of, these ground forces tick on while the city rests. Working from sunken laboratories and backstreet studios, they are faces in the crowd connected by the pride in their work – doubled in the fruits of their efforts. Alive still, the hum of a worker bee parts to white noise.

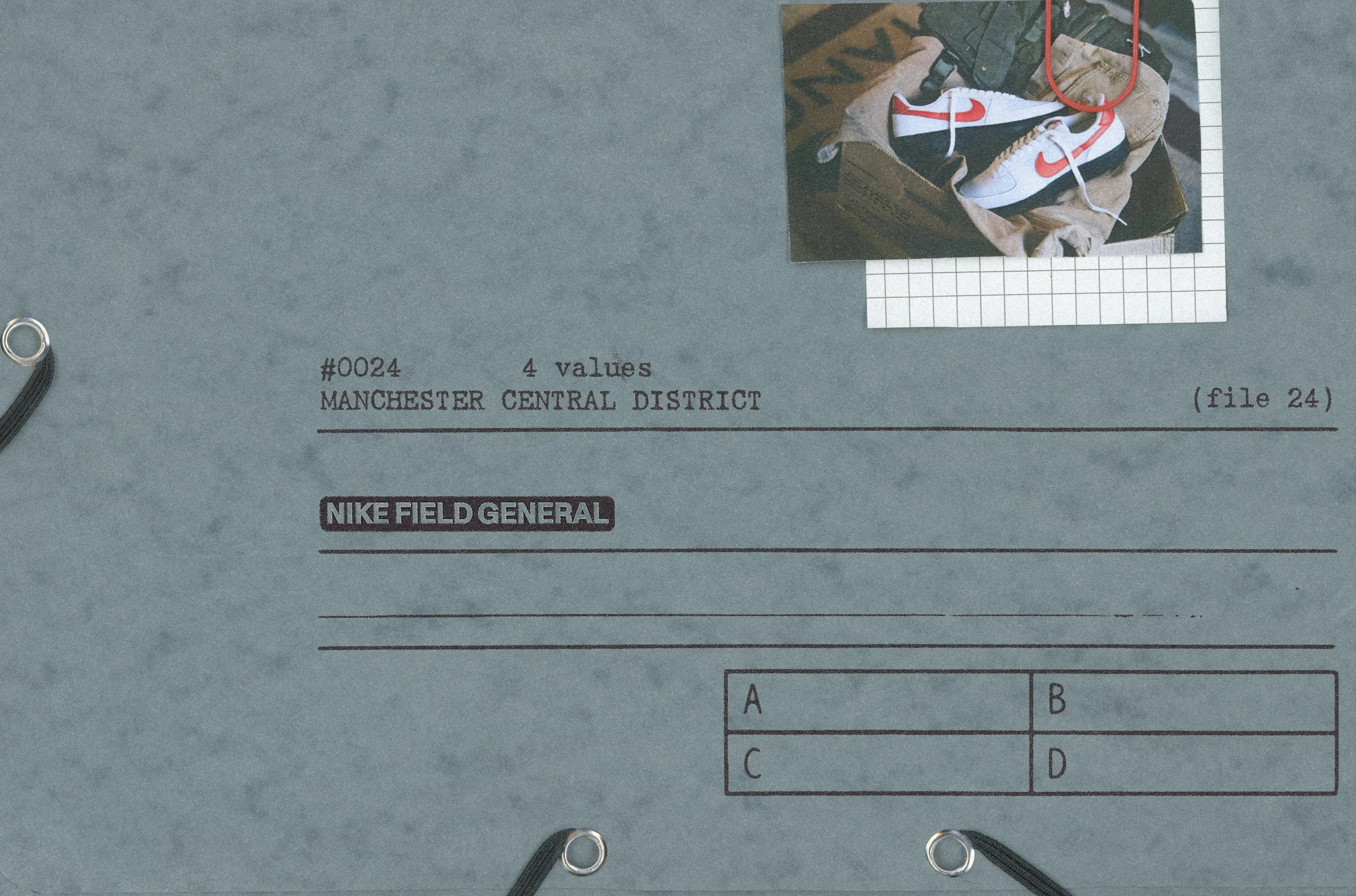

By the same ilk, a story that goes as often unspoken is that of the Nike Field General. Moving through a decade long halcyon period post the brand’s inception, a crimson Swoosh adorned a new athletic original in the year of ’82. Adorned with leather and ballistic nylon, defining streamlined subtlety with a jet-black base and versatile silhouette, its intentions toward the track and field market yet laid causation to a short-lived debut. Off the field: off the grid. Hence, with the reiterated Field General ’82 outline premiering its first appearance in 40 years, the sneaker’s incubation in the archives has preserved it from hype culture, entering an era appreciative of classic dressing and longevity. The pair then stands an apt uniform for the low-key labourer, equipped to work a day in the life of a Mancunian.

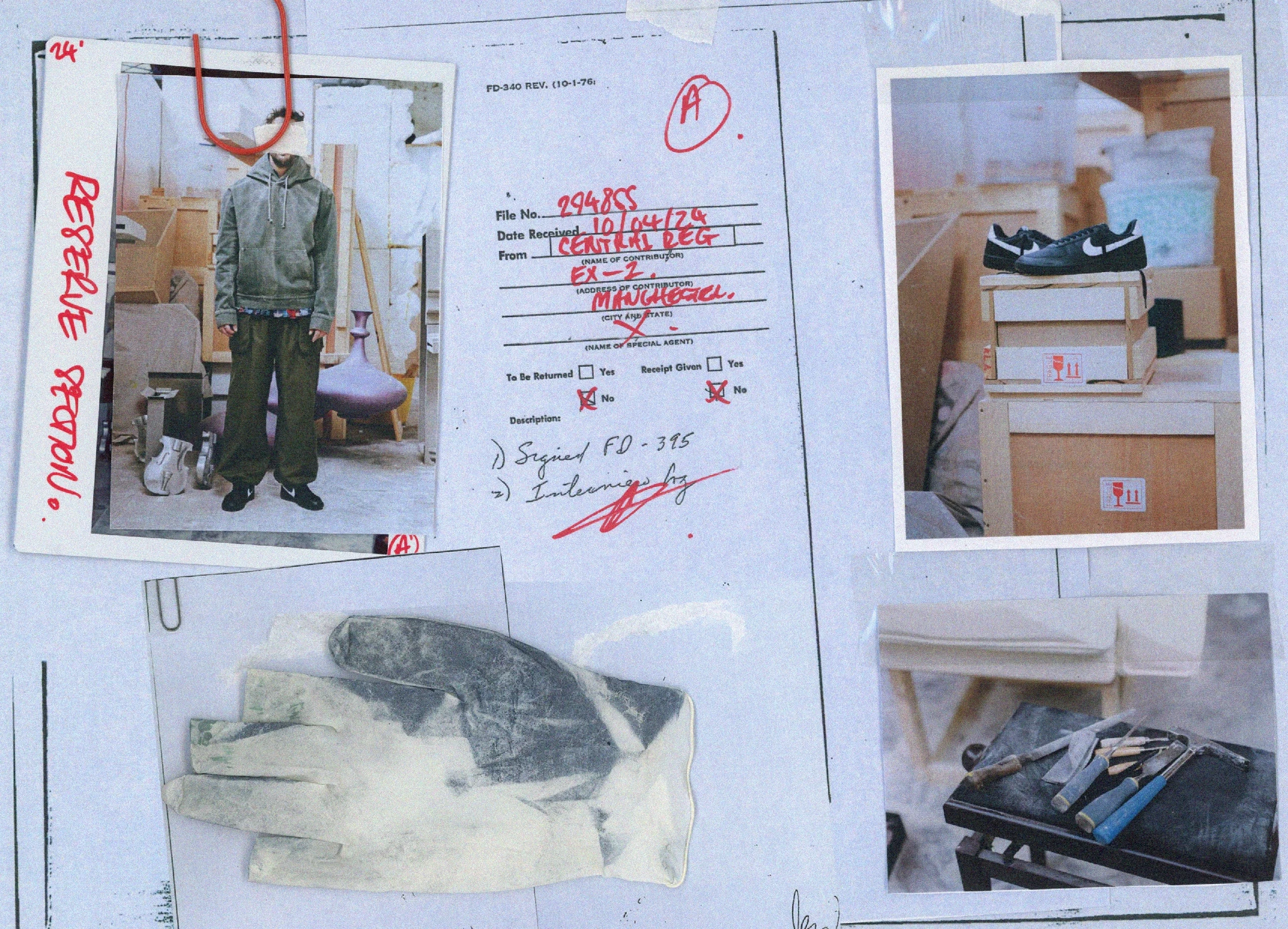

Misted with the buttery yellows of his latest project, the first provincial protagonist is as talented at hiding in plain sight as he is at perfecting his warped structures; his makerspace an isolated tram shed. Describing himself as “predominately, a sculptor”, he hints at plentiful mediums, finding his hand at realist painting as a means to impress flames atop silver resin, and outlets like “stylography” and “carving” to journey around time and the unconscious – concepts common within his artistry.

Living in the northwest throughout his entirety, the Warrington native migrated to south Manchester during his university years, tracing his present work ethic back to his paternal figure’s blue-collar background, priding the existence of the “northern graft mentality”. Thus, rising early for eleven-hour days; keeping a presence at his shared studio “most weekends”, the sculptor arises: “I could stay later”.

Additionally, he theorises that “a lot of artists are selfish”. But considering the nature of his set-design business, providing an in-house studio for “artists, designers, and fabricators” on the city’s outskirts, the set-up is comparatively nurturing: a remote branch of the landscape’s creative camaraderie. “A lot of artists in the city work in coffee shops,” he elaborates. “But [we wanted to] give them a larger income and utilise the fact they’re creative people”.

Garnering a quiet repertoire by operating without a website, the group’s client list is populated by local, mid-level fashion brands, confirming, “this place has no identity”. Inevitably, the collective circulates a whispered namesake as “the artists in the tram shed”, expressing that their elusive modus has centred them as the local industry’s “best kept secret”. The artist and his team are therefore driven by inner community above competition; their sculptural monoliths speaking on their behalf. “I want the work to have its own identity” he concludes, “my identity is my work”.

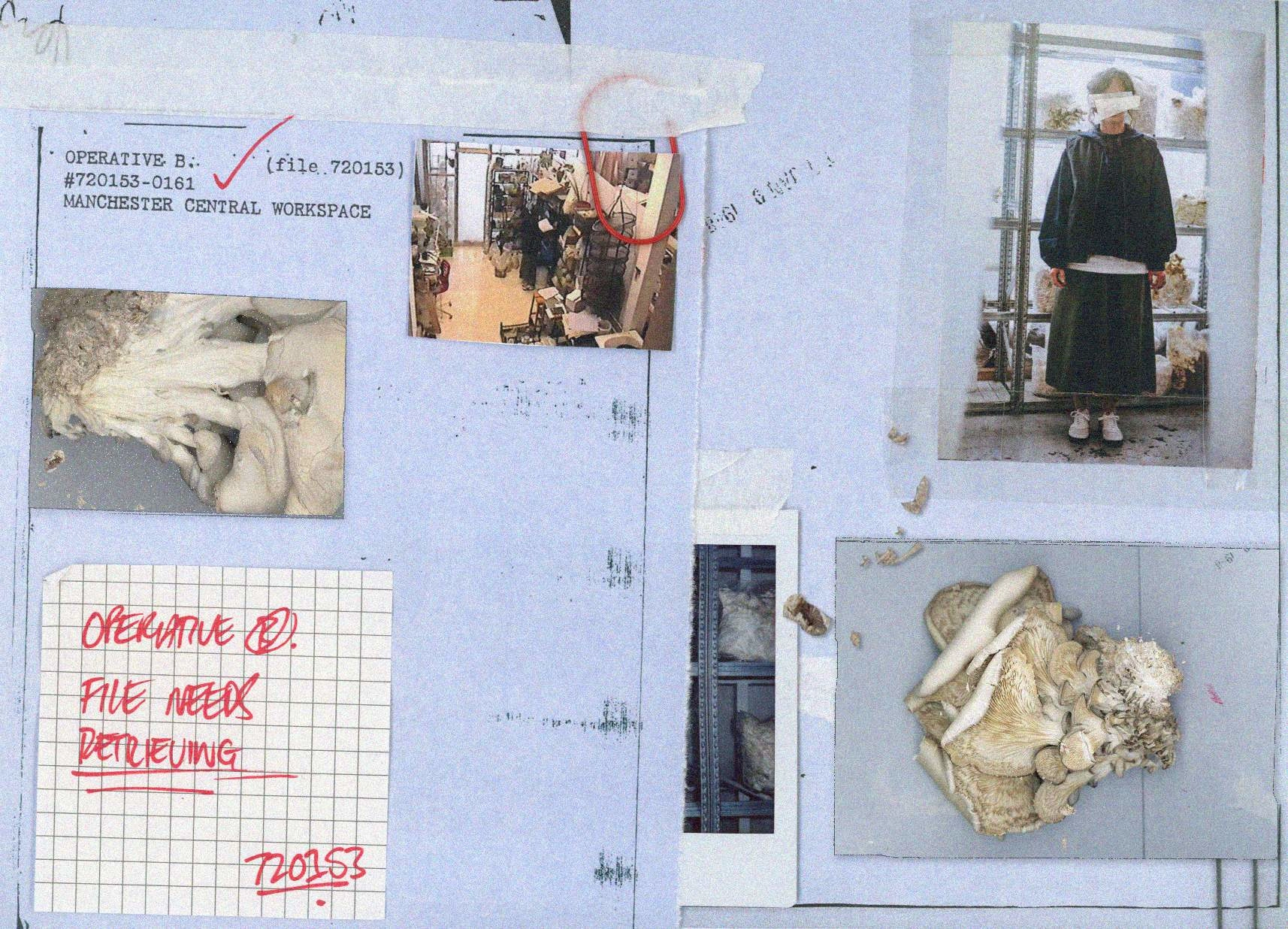

Seeding the city’s undergrowth further, the jars and petri dishes of a second hushed worker require a balance of humidity, likened to the ecosystem of built-up boroughs and small-scale farmers. Growing up in Cheddar Gorge before attending university in Manchester, the mycelial yielder has always been around mushrooms, yet never predicted to one day fund Michelin eateries with her offerings. “They’re beautiful,” she purrs.

Parting with a previous high-profile career in prop-design, the green thumb resided from any spotlight upon building her first grow room below the workings of a future customer in 2022, Stockport’s farm-to-table hotspot, Where The Light Gets In. “I shut myself away for 18 months to get the experience”, she divulges, finding the frisson in self-effacing experiment.

Describing her current day-to-day as “inoculating bags, delivering, and making time for mycelium study”, she now finds herself in a more spacious farm, carving a sunning patch between Manchester’s high-rise business quarter. And with her production’s unpredictability running an alternative schedule to the demands of the city’s hospitality market, she has shifted her efforts towards community harvesting. “We do foraging walks; cultivation classes. I want our grow room to be run by people who are learning,” she confirms of the direction.

Her workshops ripe with creativity, she cements herself within the province’s welcoming artistic cohort, praising its spirit. “Hard work comes naturally here. It’s a place to try new things,” she decides. “All the growers talk. We support each other”. A composite part to the scene, the agriculturalist finds giving back an organic process, leaning into the area’s club-in culture. “Having people learn is rewarding. I’m not interested in the other stuff. The only reason you’d like to be well known is so more people get to know about mushrooms”.

Masked with sartorial characters created from the inventories of cardboard boxes, this penultimate, silent supplier – a self-proclaimed “hoarder” – finds his hustle in the online distribution of vintage apparel and workwear. “There’s stuff everywhere,” he admits, “I’m chronically on Ebay”. Blurring the means of clocking in, his passion bleeds out, dressing the city from an unbeknown persona, tucked behind piles of fabric.

On his ushering into reselling, the Preston-born beachcomber says to have “always had an interest in clothes”; his archival criteria defined as “characterful stuff”. But despite personal trinkets, his collection speaks above any alias, revelling in what was once a mere hobby. “In Uni I’d pay for my summers by buying and selling. I’d go to every vintage shop. It’s all I do. I love it”, he expresses. Furthermore, his insular craft is inlayed with an appreciation for ephemera such as “t-shirts that are stained and holey”; driven by granting his audience access to rare gems – some “hand altered or [residing] in a garage for thirty years unseen”.

Supplying the area through ad hoc styling for brands connected by members of his inner network, the maker operates via word of mouth. Never shouting about his hideaway, he elaborates that “socially…it freaks me out, people rummaging”. Yet, somehow, he forges northern hospitality with an open doors policy. And in nestling his collection between a corridor of likeminded makers, his surroundings hold a palatable influence.

On Manchester’s four-winged, worker symbol, he concludes, “there’s less pressure to succeed than in London. I think that facilitates a different end product: working with friends, getting stuff done in a way that isn’t the norm”. Thus, taking advantage of his positioning between darkrooms, designers, and the larger, yet “tight community” of local makers, collaboration proves as integral to the city’s hive as keeping one’s head down.

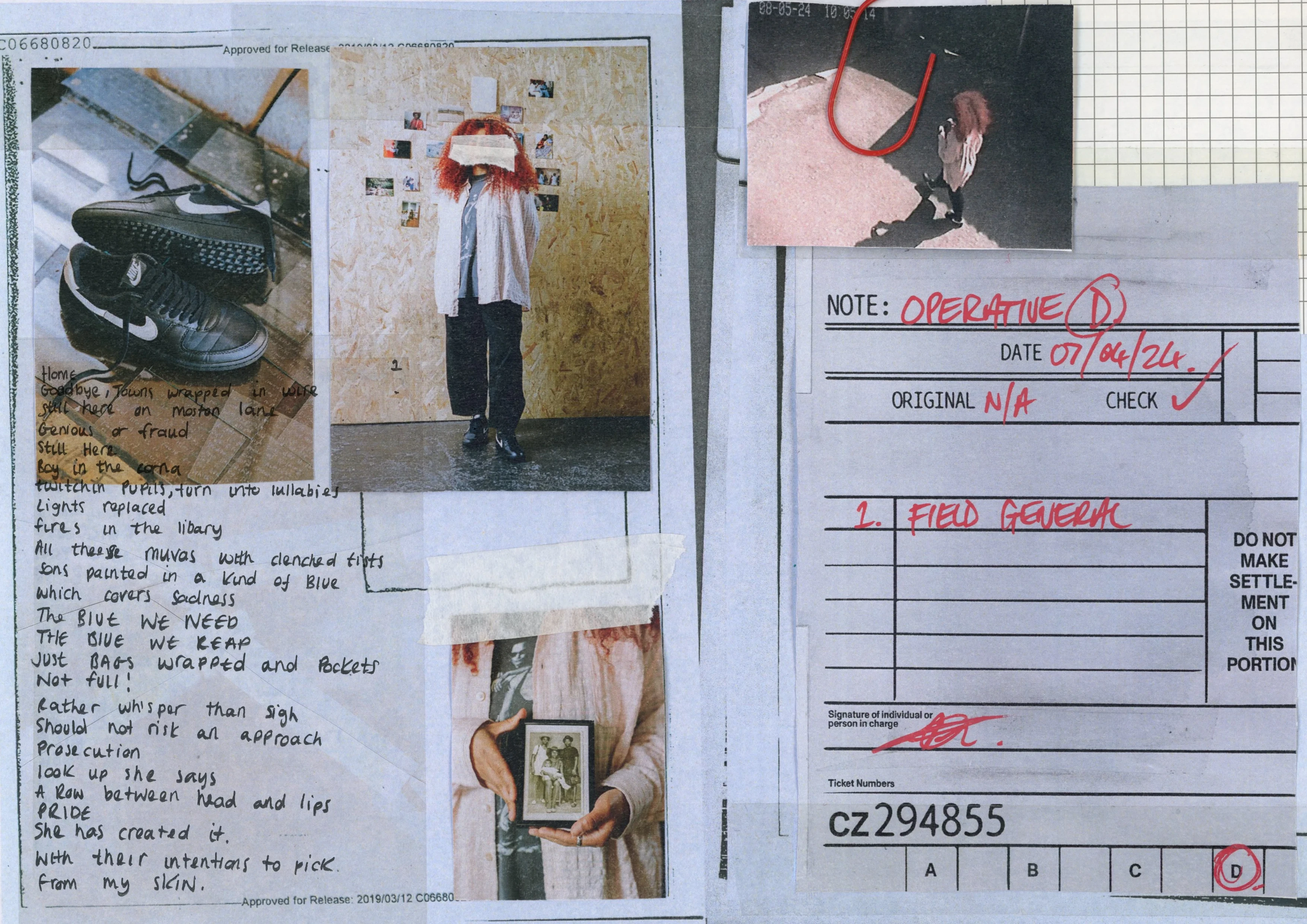

Amidst cork surfaces peppered with handwritten verses, the final internal contributor platforms the stories of others, feeding something bigger. But at the heart of it all, she’s a “filmmaker, director, and visual artist”. Tied by bloodline to west Africa and Germany, but born on a council estate in Blakeley, north Manchester, her radiant freeze-frames and audio-visual projections stay close to her grassroots, garnering spoken word collaborations with the likes of nearby musical duo, Space Afrika. “My work comes from working-class voices, whether that’s poetry or casting,” she begins. “I want to hear more northern accents. That’s what gets me up in the morning”.

Growing up in the early 2000s, the practitioner noted the creative industry’s flailing representation of people of colour, making sense of the social side projects she now finds “substance” in. “I’m also a young Black women’s group facilitator and psychosocial practitioner”. Amplifying young voices, she’s the role model she never had. Providing mental health strategies and open-floor discussions through her self-founded organisation, she submits her time as a means to better her community, a trait seemingly attributed to those in the northwest. “We’ve done exhibitions, we’ve made a film. It’s about them, it’s not about me”.

Considering the progression of northern identity, her makerspace pinpoints an industrial heartland, clarifying: “It’s hard to be a freelancer in the north. I graft because I had to”. Fortunately viewing the Mancunian, creative coterie as a “family”, lending a hand runs as timely as its toiling heritage. “People see us as hardworking, but there’s a vulnerable side – a softness that doesn’t get told”. Arising that its hard edges have rounded with communion, the city’s hidden operatives are unified by something deeper than clout. “I don’t want to be an individual where I’m not sending a message that lasts longer than me,” she concludes.

Risen from factory smoke, today’s hushed workforce creates purposeful experience away from the digital feed and Manchester’s once tough exterior. Hence, collaboration provides an offline alternative, and sharing the load comes as second nature as getting the job done. Thus, the interplay between city and citizen is akin to the reliance of the quiet worker on the Field General 82. Driven by the granularities of their own specialisms, for Manchester’s operatives, hard work – like the low-key legacy of Nike’s track-born hero – never dies. Where putting in a shift has a collective result yet speaks of originality, don’t shout about it: just play the field.

Like this project

Posted Jul 7, 2024

In response to the client brief from Nike, I worked alongside the creative director to reflect a story of underground makers; thus keeping them anonymous.