ARTIST INTERVIEW: Rui Matsunaga and the Myth of Survival

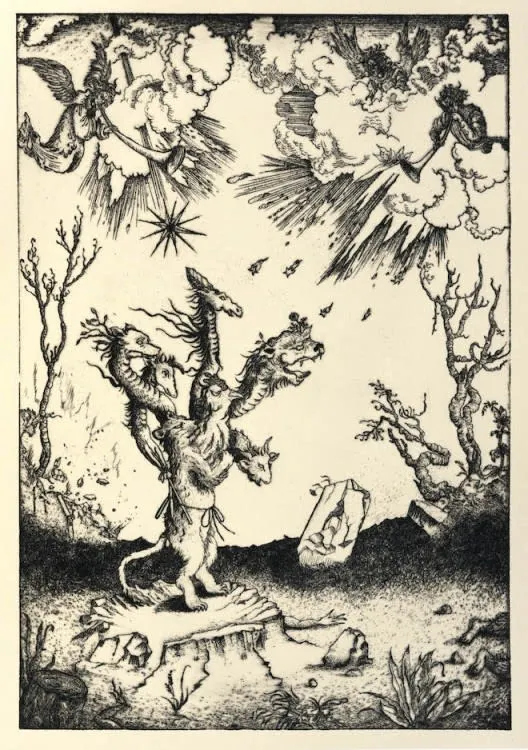

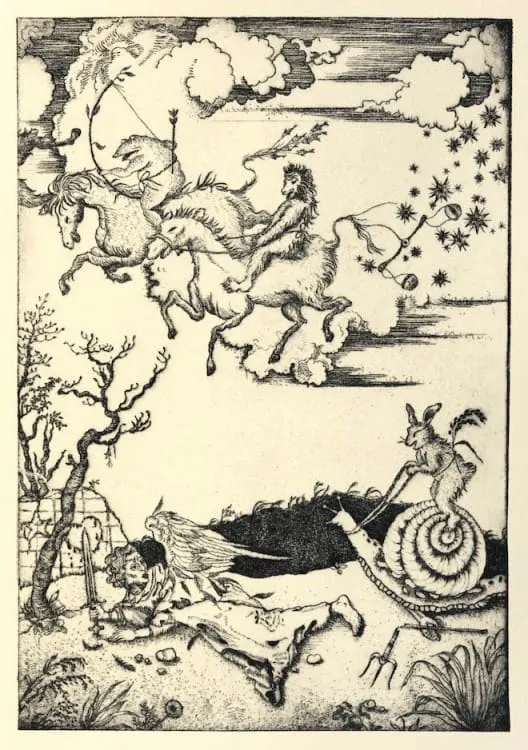

Rui Matsunaga, a Japanese artist based in Yamaguchi, is obsessed with the end of the world. Over five years she has examined the ‘apocalypse’ through various perspectives: the works of Dürer, animism, tribal and religious myths, and climate change. The result? A series of oil paintings and etchings, populated predominantly by tribes of frogs and rabbits, which play out scenarios in an ecological armageddon.

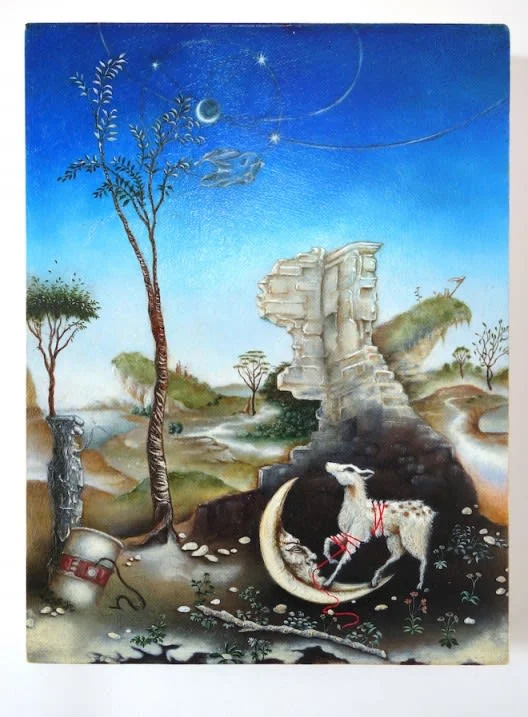

The etchings look as I had expected — like relics from mystic manuscripts — but I hadn’t realised how small and bright the oil paintings would be. Electric blue skies, luminous white pebbles and paintwork so fine she catches the disgruntled expression of a haggard moon in the space of a thumbnail.

As I move, the sun catches on stars and comets texturally embedded into the paintwork. Matsunaga paints one world we immediately see, and one which can only be seen from certain angles, in certain ‘enlightened’ moments.

Matsunaga’s voice is soft and small, but not subdued: her words fizz with an infectious vibrancy, and 10 minutes into the interview, I realise that the room about us has fallen away. Matsunaga has drawn me into a dance, and we step together fluently through conversations of metaphysics, art and the occult.

Alice Gee: With access to Google and living in such an analytical age, do you think we’re losing our ability to tell or make myths? We used to make them in the absence of ‘answers’, whereas now we have answers readily at our fingertips?

Rui Matsunaga: I feel like we still keep going back to the three basic myths: the creation myth, the hero’s journey myth, and also a big one, the end-time myth: ‘apocalypse’. The works I’m showing you here today centre around this end-time myth. The famous one is, of course, in the Bible, but most religions, spiritual groups, or any tribe have their own end-time myths. I think it’s almost primordial that we have this fear of life and death, and also the way we bear this fear is to create a basic myth. We need it in order to understand who we are in relation to the world we live in.

Back when we had tribes, tribal myths helped us understand who we are. A child becoming an adult has a ‘rite of passage’ or a hero’s journey myth. These rituals help you realise, okay, I am an adult now, I’m going to behave differently. Today’s equivalent myth is, for example, if you wear a school uniform there is a mythology around that: it creates a kind of identity, a symbolic one, and immediately you can place yourself in society: ‘I study in this place, this is who I am’.

As long as we live, we need to understand who we are, and we need these stories to make sense of who we are. Even today in a Google world where we can look up anything, still, we need myth.

Rui Matsunaga, On the Moon, 2019, Oil on plywood, 20.5 x 15 cm (image courtesy the artist)

AG: Talking of searching for your identity, what are your earliest memories of something creative or artistic that inspired you?

RM: I guess children’s books and films and TV series — Godzilla, for example. Godzilla’s a powerful monster, but he was just a little salamander, which became exposed to radiation and became humongous and destroyed everything. At first, it’s about fear of monsters and defeating them. Then, on a deeper level, it becomes a social commentary of the dangers around nuclear power in Japan, and then even deeper is the fear or memory of the atomic bomb in World War Two. So I realised: this children’s story, which I enjoyed on a superficial level, was actually expressing much more complex historical and social ideas.

AG: Godzilla is a perfect example of the three basic myths: there’s the creation myth of something gigantic from nothing, and an explanation for the seemingly impossible. Then the hero’s journey, which is killing the monster. Then there’s the threat of apocalypse lurking in the background — a destructive force in the world, the bomb, that could destroy everything.

RM: Yes!

AG: So you start with these visual and narrative sources of inspiration, like Durer’s Apocalypse series, or the Bible. But when you sit in front of your ‘blank canvas’, how do you position these characters and create these wonderful and bizarre compositions and narratives?

RM: The practical method is that I do a lot of drawings — especially of the animals. I take a lot from Japanese scrolls and manuscripts, and I draw and stick them onto the wall. My studio is full of drawings. Then I just look at them, and wait for them to create their own stories.

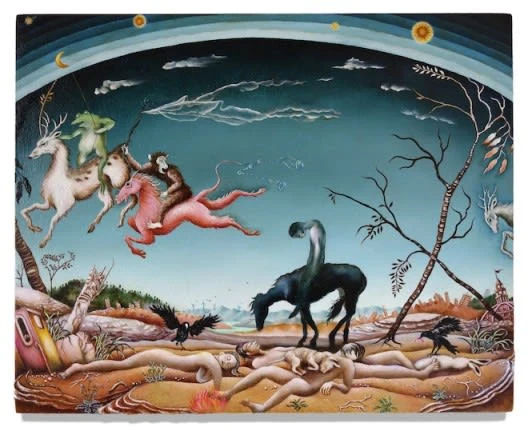

Rui Matsunaga, Ride of Discord, 2020

Oil on plywood, 20 x 25.5 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Some of them are based on Christian mythologies, or other mythologies. So, there are some basic ideas which I then adapt to today’s context. For instance, how do we now relate to the ‘Saviour image’? It’s no longer Jesus Christ who is the Saviour image we have. Instead, the image of divinity might be an algorithm, or the image of AI, which might now symbolise transcendence.

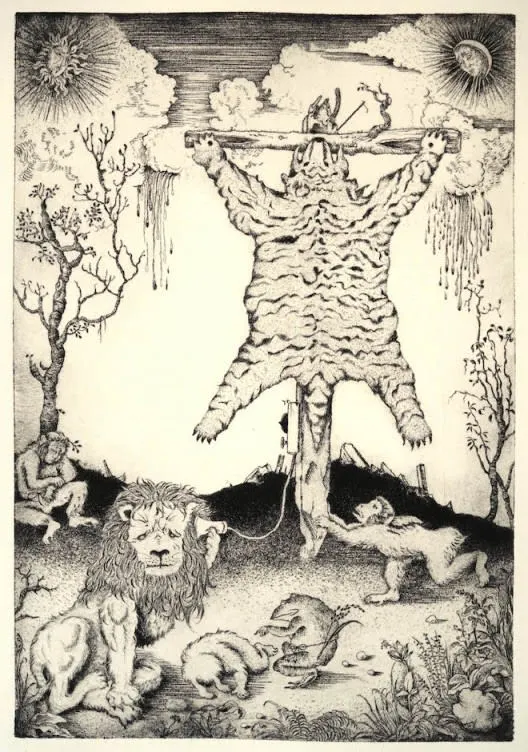

AG: A spotlight upon these false idols that we now have, perhaps. There’s one particular piece where there’s a tiger skin on a crucifix that’s been skinned as a sacrifice to human greed…

RM: …And also, because of a lack of communication, because we don’t communicate with the natural world. We are so mortified by the crucifixion of Christ, why are we not as mortified by the sacrifice of tigers? We can shut down our sensitivity towards not only tigers but also other animals, and we repress our senses and sympathy so that we can eat them. Otherwise, we could not do so. And if we really think about that, it’s a small step away from a wider dullness in society where we have absolutely no emotional sympathy for other beings or for each other, which is so dangerous.

Also, we live in a monotheistic society, so whilst we may no longer have a strong religion, money has become…

AG: Our new one god.

RM: Right! So, even love and care have been given a price tag, even ‘spirituality’ has price tags. Everything now exists in relation to money. And what we are losing as a result is the internal — the ‘out of reach’ — or that which we can only try to pinpoint, through poetry or Oracle tradition or something instinctive. Because we can’t fully grasp this aspect of the world, we can’t put a price tag on it. It’s invisible, and I refer to this internal nature in my work as well.

Rui Matsunaga, Chiming Stones, 2016

Oil on plywood, 30 x 40 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Rui Matsunaga, Chanting Chrysalis 2016

Oil on plywood, 30 x 40 cm

AG: It strikes me then that there’s two kinds of decay or environmental crises depicted: one an external, ecological one, but also another of the internal spirit.

RM: Yes, I think so, and the internal one is more crucial than the outside one.

AG: Perhaps we can’t truly solve the environmental crisis until we solve the internal one. Leading on from that, with the internet and Zoom calls and modern technology, as an animist, how do you feel about this new kind of ‘interconnectedness’?

RM: I think it’s a complex issue, because on the one hand, you mentioned for example, when we have virtual meetings, what we have in front of us is actually just a monitor, but we adjust our mind to consider that a real person is in front of us, and we behave in that way, so that our mind is adjusting to that type of new reality that we are forming.

Not only that, technology increasingly addresses what we have considered metaphysical before: like immortality and death. Now, science is trying to solve death, as if it’s a technical problem. If you’re elite, you can be treated in various ways, with the aim of anti-ageing and eternal life. So, what is the definition of death? Is it now a technical problem? And if so, then what is the definition of life? These questions used to be divine questions, but now scientists are dealing with them.

AG: Before the interview, you mentioned that we need darkness to have light — and you capture both through violence and humour in your work — and it struck me that what you’re suggesting, about society looking and seeking for immortality, is that the further we embark on this quest to eradicate the dark, against death, against mortality, the more we compromise the light in the world, until everything is numbed into some grey dullness.

RM: Yes! And they are also trying to define ‘what is light?’ ‘What is consciousness’?

AG: And then ‘let’s sell it’!

RM: Yes! Yes!

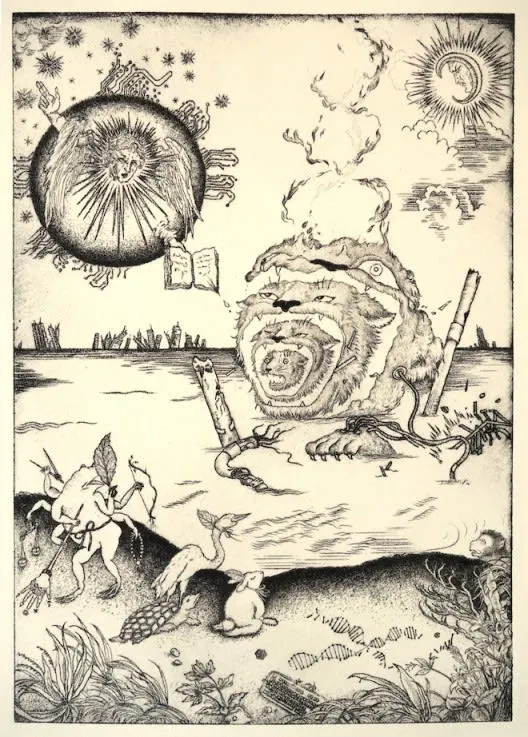

Rui Matsunaga, Beast from the Sea, Edition of 5 (AP3), 2018,

from the Apocalypse series, Drypoint, 30 x 20.5 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Rui Matsunaga, Fearful Symmetry, Edition of 5 (AP 3), 2017,

from the Apocalypse series, Drypoint, 30 x 20.5 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

AG: Is your next project about this theme?

RM: It’s actually about Dante’s Divine Comedy. Some people say that Dante actually experienced this journey through hell and paradise. I thought this was interesting, because a Siberian Shaman also had a similar experience, lasting three days. He went into the abyss, and gained knowledge that normal perception doesn’t allow.

Again, this story has a hero’s mythology, one which we can apply to our own psychological experiences, or how we deal with the subconscious. We live in reality, but there is another parallel world which is more emotional or metaphorical, which is where a lot of our everyday decisions come from.

AG: Even if we don’t realise so. Nietzsche uses the characteristics of two Greek gods: Apollo, who represents rationality, and Dionysis, who represents emotions and instincts, to illustrate this internal struggle. But back to the work: how practically, in what medium and style, do you envision this series?

RM: At this stage — like the Apocalypse series — I’m doing a lot of drawings and etchings, and then I will paint based on the etchings.

My visualization of the Divine Comedy is about going deep inside the psyche. That’s the funny thing about the Divine Comedy. It’s almost like Dante suggests that the more you go down and deep into yourself, an ascension happens. It’s a paradox of life: the deeper you go, the wall or mental block you have falls away, and you ascend as a much freer being.

That’s actually one thing which I’m having a little difficulty with right now. Depicting hell is the easy bit, but depicting heaven is tricky. Botticelli did an amazing job of capturing what is ‘beyond’ our recognition of beauty. Towards the end of his drawings or etchings, it’s almost like you can’t see the lines anymore, the beautiful flowers and light, they become so faint…

AG: The boundaries fade away!

RM: Yes! How can you contain light!

AG: We spoke earlier of exploring both external and internal crises that humanity faces. I think many of us can relate to going through a really dark moment, having to come back from that, and perhaps then having a radically new perspective on life — maybe depression, or grief, or living through a plague! Does this depict a personal journey for you too?

RM: Yeah, totally. As an artist, you have to go there, to those dark places. I was almost thankful that I had art to be able to express those emotions in a way that was both therapeutic, but also helped me to investigate this darkness a lot more. Like you said, after those experiences, life is different, and you read it differently.

Like Dante’s story, it puts you into perspective that all of this, all these experiences, are part of a journey. When you reach the bottom, you need to remember this is not a place you are going to dwell, but this is a journey. All my works illustrate the cycle of life, even my ‘apocalypse’ series: they are about the end of the world, but also about rebirth. That’s very important.

Rui Matsunaga, On the Moon, 2019, Oil on plywood, 20.5 x 15 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Rui Matsunaga at Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, London, 2021

Rui Matsunaga, Beast, Edition of 5 (AP 3), 2017

from the Apocalypse series, Drypoint, 30 x 20.5 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Rui Matsunaga, Four Riders, Edition of 5 (AP 3), 2017

from the Apocalypse series, Drypoint, 30 x 20.5 cm

(image courtesy the artist)

Like this project

Posted Aug 17, 2023

Interview with John Moores Painting Prize finalist Rui Matsunaga for the Ran Dian magazine. Her works are exhibited in venues such as the V&A, UAL, SOHO house.

Likes

0

Views

18

Tags