Olmsted and his 'Writings on Landscape, Culture and Society'

The Father of Landscape Architecture: Frederick Law Olmstead, Illustrator: Gaby D’Alessandro for ©The Atlantic

Frederick Law Olmsted, born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut, was a pioneering landscape architect in 19th-century industrial America. Before he became known as 'The Father of Landscape Architecture,' he was an apprentice seaman, a merchant, a journalist, and a farmer. During his time, he wrote many influential books, articles (for publishers like the NY Times), and letters to change-makers like Abraham Lincoln. He even co-founded the prominent publication, The Nation, during the Civil War. At a time when America faced many racial and social divides, Olmsted's values for a democratic and equitable country were equally eminent both in his rigour for driving social change on issues like slavery and his commitment to designing public parks as a quiet and peaceful haven in an otherwise crowded and loud cityscape.

A Brief History of Parks

Cemeteries as Parks in the 1800s, Photographer: Highsmith, Carol M. (1946) © Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Before the design of public parks in American cities, cemeteries and graveyards were the chosen destinations for city dwellers to frolic on a weekend afternoon. Parks then were almost exclusively referred to in a private context. They were usually large expanses of manicured grounds owned by wealthy landowners for activities like deer keeping. But, in the modern city, there was a neglected public desire for open spaces to walk carelessly and bask in rural green landscapes without leaving the city or bumping into a mourning family. Olmsted saw public parks as a democratic remedy for the quickly urbanising cities of the 1800s that were becoming 'formless' in both physique and social community.

Olmsted: The Father of Landscape Architecture

"It takes a lot of artifice to create a convincingly natural scenery" - Frederick Law Olmsted

Olmsted designed thousands of urban green landscapes in the 19th century, starting with Central Park, New York, and including many other prominent parks in America, like Boston’s Emerald Necklace and The Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. Throughout his career as a landscape architect, he created sets of rules and principles that would become the cornerstone of the profession of Landscape Architecture. The basics of Olmsted's aesthetic theories of landscapes can be summarised as follows:

A park should complement the city to which it belongs.

Olmsted believed that for a park to seamlessly integrate with a city, it must contrast with the urban fabric while harmoniously connecting to its surroundings. In a grid-like, rectilinear, rigid, and dense city such as New York, Central Park was designed to have large open expanses of green lawns and winding paths amid asymmetric and deliberately chaotic natural landscapes. Olmsted's park design also facilitated a circulation of pedestrians and vehicles that allowed city traffic to continue across the park without disturbing its serenity, complementing the city aesthetically and functionally.

Sheep Medow, Central Park, Photograph by ©Yourdon CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

A park should be faithful to the character of its natural terrain.

His second principle, influenced by his time as a farmer, was to grow a landscape reflective of the ground it stands on. He observed that plants that are decorative or ornamental and not native, although standing to be beautiful on their own, become 'out of key' with their surroundings. Learning and understanding the undulations and movements of the terrain is key to designing a functionally resolved beauty.

Natural Terrain, Photograph by ©Kpaulu, CC BY 2.0

A park must create a convincing ‘natural’ scenery.

Olmsted saw the irony of this third principle and was often troubled by it. Everything about this profession that he unintentionally created was man-made. Yet, the most important objective was always to create an idealisation of nature, a human attempt at an imitation of its curated randomness.

Frederick Law Olmsted, plan, 1869, © 2024 Smarthistory

Recognising Olmsted's revolutionary influence on the profession of Landscape Architecture, the Library of America released a collection of Olmsted's work aptly titled 'Olmsted: Writings on Landscape, Culture and Society,' which includes a look into his reflective letters and reports and plans of some of his most influential parks. For readers who don't have the space to shelf or time to read all 12 volumes of Olmsted's papers, the book is a quick grasp of his ideologies and a seminal text for all architects.

An Artist's Work in the City - Central Park, New York

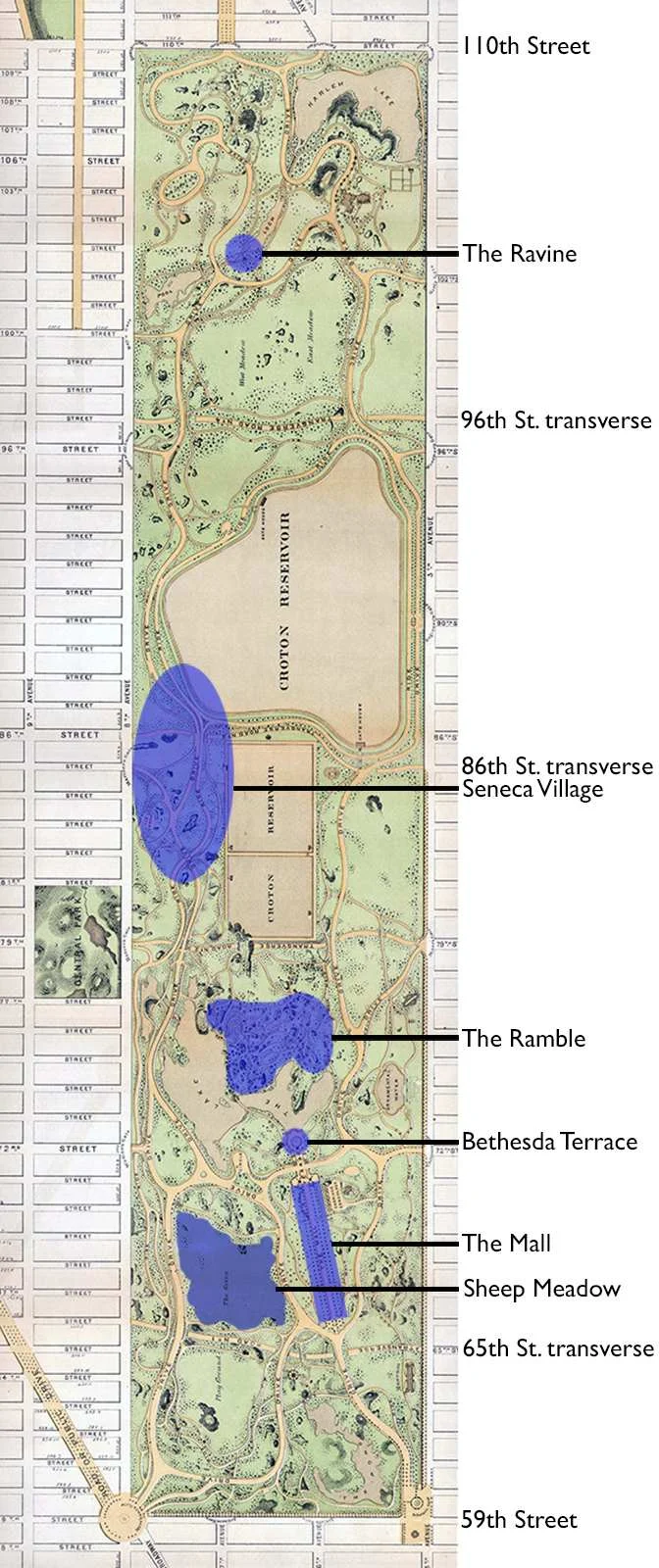

Central Park, designed by Olmsted along with Calvert Vaux, is an exemplary work of landscape design that has stood the test of time and, to this day, remains a subtle and artfully designed yet unassumingly natural landscape for the people of New York to enjoy. It was the first opportunity that came Olmsted's way to dive into the world of landscape design, and its success spearheaded The Park Movement in America.

The basis of the aesthetic principles he applied to the park design of Central Park was 'unconscious influence.' Instead of attracting attention, he wanted his park designs to blur into the background without interrupting conversations or stopping people in their tracks. He attempted to create a beauty of the whole and not the parts; an elegance that cannot be viewed or admired, only felt.

An Illustration of Central Park © 2024 Bella Foster

References:

Rich, N. (2016) 'Frederick Law Olmsted and the creation of Central Park,' The Atlantic, 12 August. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/09/better-than-nature/492716/.

Landscape Design 101: Olmsted-Inspired Design Principles in NYC’s Parks : NYC Parks (no date). https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/olmsted-inspired-design-principles-in-new-york-city-parks.

Olmsted Theory and Design Principles - Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service) (no date). https://www.nps.gov/frla/learn/historyculture/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles.htm.

Ranogajec, P.A. (no date) Smarthistory – A breath of fresh air, NYC’s Central Park. https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/central-park-sa/.

Like this project

Posted Sep 15, 2024

Reviewed Olmsted's impact on landscape architecture, exploring how his principles amidst rapid urbanization revolutionized 19th-century park design in America.

Likes

0

Views

21