Duchamp and the Future of AI

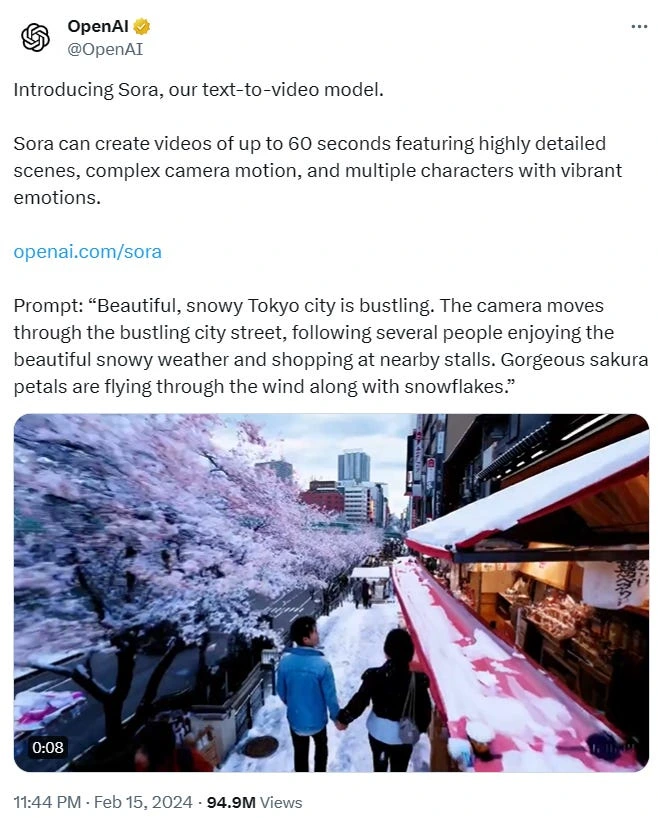

In February this year, Open AI announced the development of Sora AI, a text to video model that could potentially change the meaning of media and art in the very near future.

Almost over a month has passed, and it feels like we’ve been preparing for this for a while since ChatGPT and DALLE, and this news like most others has drowned in the storm of worse things happening around the world. But somewhere in the back of our heads we know, this is the beginning of something that we’re not prepared for.

Thanks for reading The Loop! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Obviously, democratizing this kind of power can mean ‘Anyone can do anything’, every aspiring film student or drama club teenager or writer living in a basement would have the power to create limitlessly, but unfortunately it also means that ‘anyone can do Anything’ (to simply put it).

OpenAI claims to be currently testing the model with selected groups of researchers, artists and video creators to understand its threats and potentials. I don’t know about you but, believing that these humans will have any control over what is about to unleash into the world, would require a level of optimism I do not possess.

Beyond safety concerns, there's also the question of what this means for artists and creators in the industry who have dedicated their lives to their work, and now face the possibility that an AI could perform their jobs as well or even better than them. And this is of course not limited to media. It almost feels like every month there is a new AI in town terrorizing the foundations of our economy. Only a few days ago, I heard (on my trusted and certified source - ahem Instagram) from a recently graduated software engineer, talk about a self-learning software development AI - Devin, that would most definitely put her 4-year degree to absolutely no use.

The truth is whether we like it or not, for better or for worse (most probably for the worse) these changes are happening. In this slowly realizing dystopia, where our work and our craft is losing its meaning how do we look to the future with hope? As artists, architects and creators how can we even begin to prepare for a change like this?

One thing we can do, when our future is starting to look uncertain, is to look back to a time when our present was uncertain to people in the past. Not because they were legends we have to idolize in thick history textbooks, nor were they all NPCs who were poor, famished or miserable due to larger world problems. But, simply because they were humans, just like us. Humans who loved and erred.

One such human, who might have a story that can help us with our little situation today is an artist I really like called, Marcel Duchamp.

Full disclaimer, this narrative is based on a part of an episode of ‘The Dictionary of Useless Human Knowledge’, a South Korean tv program, where they feature panelists from different fields like astronomy, physics, forensic science and arts, to sit together and talk about everything that is human. It is a very long, funny and interesting show that I would 100% recommend. In episode 6, each of the panelists talk about ‘A person who will change our future’, when everyone else was expecting a conversation about another revolutionary scientist or inventor, Physicist Kim Sang Wook brilliantly narrates this story about an artist, Marcel Duchamp, that stuck with me for a very long time.

A quick history lesson.

Academism

In the 19th century after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the dominant style of art in Europe was Academic Art or Academism, which reflects the teachings of the École des Beaux-Arts, the Parisian state-sponsored art academy. Painters cared a lot about the technique and draftsmanship of paintings, to make them smooth and utterly devoid of any brushstrokes. Characterizing rationale and proportionate perspective, clear focus on the subject and proper shadows, the paintings were, I would say, godly.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres- Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn (1825–1860), Princesse de Broglie , 1851–1853 - Oil on Canvas

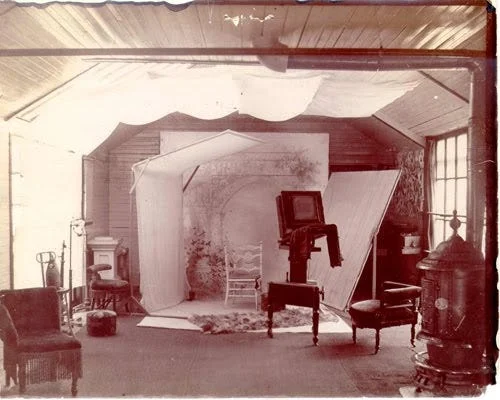

Around this time there was a very significant invention that was slowly cooking, waiting to change everything into what has become art today - The invention of the camera.

Kishungk!

The scientific knowledge of cameras was known long before the 19th century actually, in the form of camera obscura, literally meaning ‘dark room’ in Latin (at least according to Wikipedia), because the camera was an actual small, dark room with a tiny hole or lens. It was Louis Daguerre who in 1837, created the world’s first photographic camera. His invention reduced the exposure time of photographs from 8 hours to 30 minutes. When his invention was announced, it very quickly moved thorough the Europe, in a time when the industrial revolution was starting to take hold, Daguerre’s ‘daguerreotypes’ quickly began being perfected and produced in several industrial nations. By the 1840s, photography studios started to pop up in England, and by the 1880s, the invention of film rolls made photographs cheaper and more accessible. For the first time now, art was democratic, to have a portrait of oneself wasn’t exclusive to the wealthy but an occasional spending of the middle and lower classes too.

Photo Studio in the mid-late 1800s

By the end of the 19th century, it was Kodak that began the real revolution when George Eastman perfected the exposure time of photographs to be one second - one click.

Impressionism

Artists who grew up and practiced art during the advent of photography, saw art differently. They knew it had to be more than what they were taught it was to be in school, art could soon be unable to outdo what a photograph does. So, it had to do what a photograph couldn’t do. This was the birth of Impressionism. Impressionist explored other aspects of a painting, beyond what was the image - the colour, light and movement. What is the colour, light and movement that the human eye captures, what do I see in this moment?

Claude Monet - Impression, Sunrise - 1872

Impressionism in many ways opened the doors for a shift in perspective, although ridiculed for its low-quality images in the beginning people soon started valuing it for what it did. Artists found new ways to break the realistic image, the subject and its form to its essence.

Cubism

By the early 20th century, photography had evolved into film as a brand-new medium of representing reality, and these ‘moving paintings’ quickly gained popularity. Cubism attempted to do something neither a photograph nor film could do. This movement rejected the rules of three-dimensional drawing, and represented subjects as two dimensional, often including multiple angles of viewing at the same time.

Pablo Picasso - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Paris, 1907

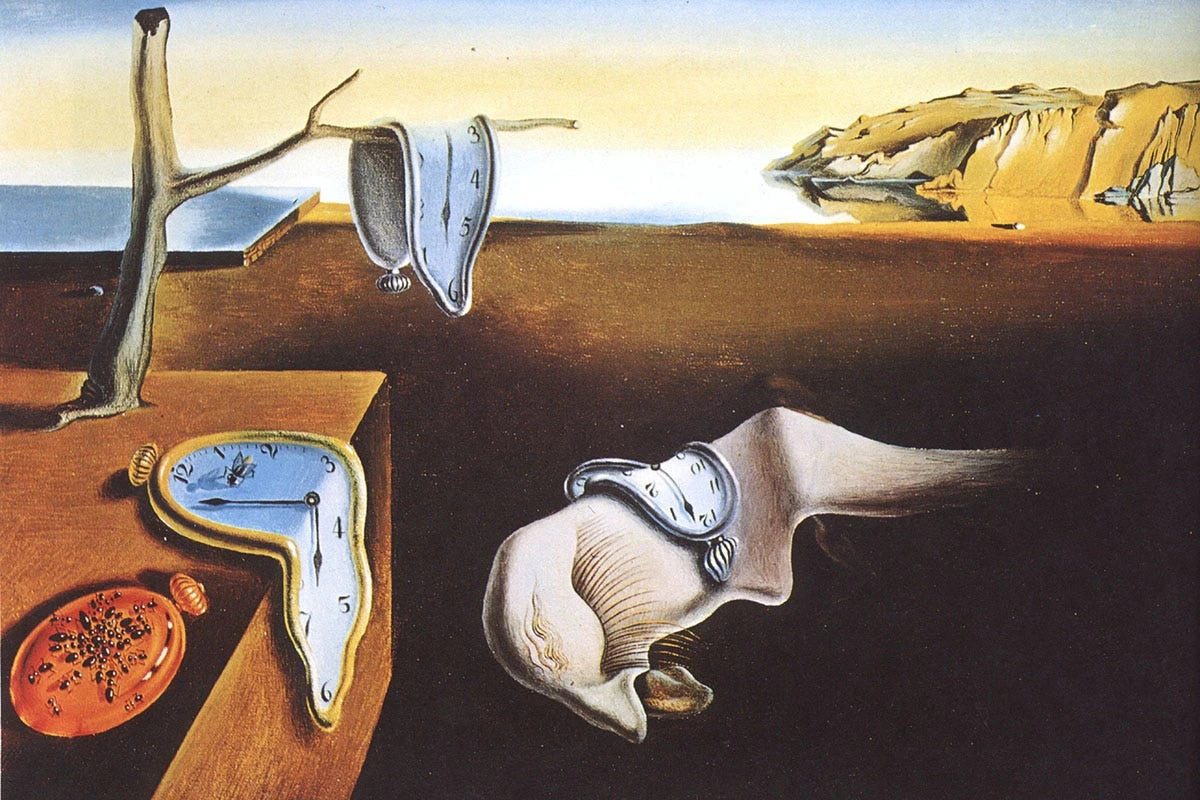

The years after the invention of the camera, were truly transient times for the art world. The genesis of many movements was maybe directly or indirectly a response to this change, a tireless endeavor by artists of different periods to keep creating something a machine could never do. There were many other movements like Expressionism, which captured the emotions of the artist, through thick brushstrokes, vivid colours and dense medium or Surrealism that realized images we cannot see through our eyes but only in our dreams and imagination. But in some ways, all these movements were still tied to the image in its essence, they were still competing with this machine, to prove human value to the world in different ways.

Salvador Dali - The Persistence of Memory (surrealism) - 1931

This was the time that Marcel Duchamp was born into, and this is where our story really begins.

Marcel Duchamp

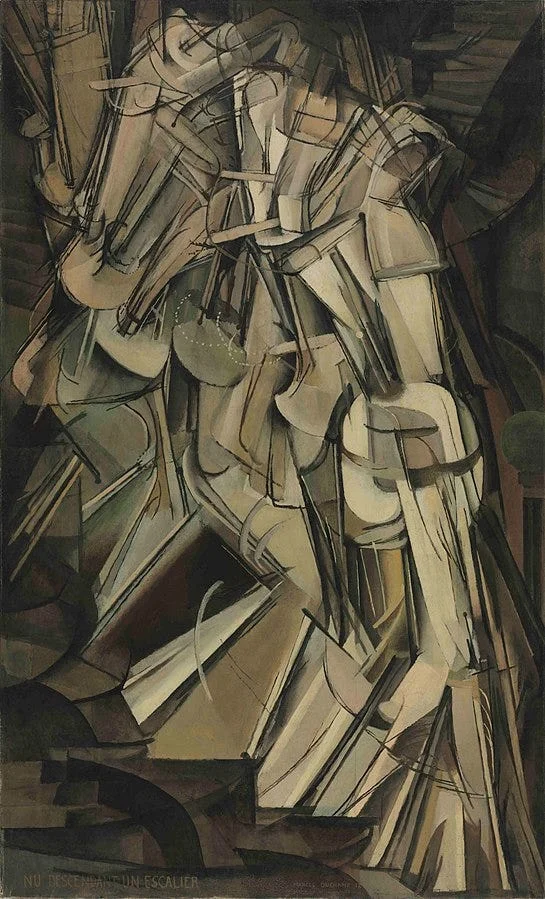

Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887 and started painting in the beginning of the 20th century. This was a time when cubism was very popular. Although he considered himself a cubist, his work wasn’t really accepted as one by his fellow cubists in France. His painting ‘Nude Descending a Staircase (No.2)’ seemed cubist but something was different.

Marcel Duchamp - Nude Descending a Staircase (No.2) - 1912 - Oil on Canvas

Cubist paintings were made from looking at a subject from different angles and juxtaposing them on a flat surface, but this painting seemed to capture the dynamic movement of a subject through time altogether on a single surface. So, when he tried to showcase it for the exhibition in Paris 1912, the committee tried to exclude it suggesting that he should fix it. When the work was finally presented in at the Armory Show, in New York in 1913, it gained a lot of attention and critical response. To the Americans, Duchamp’s style was shocking, one critic famously described it as “an explosion in a shingle factory”. So, he stayed in America and continued to shock people and reorder the rules of artmaking for a while.

This was where he developed his idea of ‘ready-mades’. A ready-made is an ordinary manufactured object (or objects), that an artist by simply choosing and repositioning, titling or signing it, transforms it into art.

Marcel Duchamp - bicycle wheel (created 1913, third version exhibited 1951)

At that time in the US, ready-mades referred to mostly readymade clothes. Before this, clothes were stitched for each person, as factories began mass manufacturing, clothes could be made in bulk for a lot of people. Duchamp’s idea was to choose these mundane objects in everyday life that has no craft, or particular beauty and then to abstract it from its function and simply declaring it as art, and he argued that in doing so it became art. This was a reaction against what he considered ‘retinal art’.

“Retinal art concerns only what the retina receives. The colours and the forms, [are] not much of an anecdote. I didn’t like it, I never liked it. So, I tried to do something else. To avoid to do something only appealing to the retina.”

- Marcel Duchamp

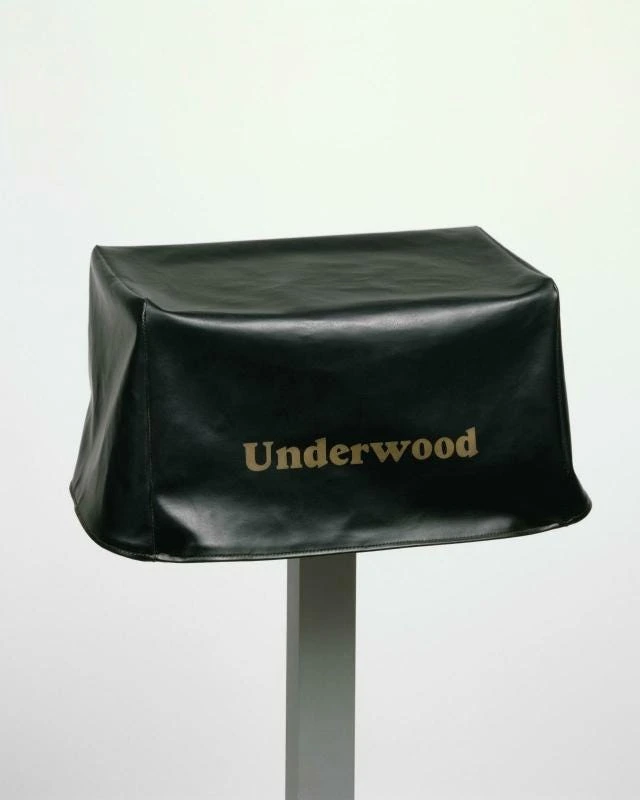

His first work was exhibited in 1916. It was a typewriter cover, from a brand called Underwood. He exhibited it, but at the exhibition, he placed it next to the entrance, without an explanation, so no one even realized it was part of the exhibition. Duchamp realized that this wouldn't work, unless he does something shocking, his efforts wouldn't be recognized as art.

Marcel Duchamp - Traveller’s Folding Item (Pliant de Voyage) 1916

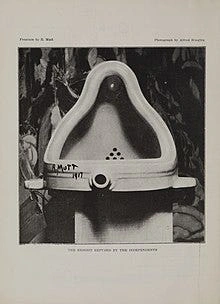

On April 10th, 1917, he decided to shock the world by submitting a urinal to an unjuried exhibition in New York. He bought it, signed it with a pseudonym -’R Mutt’, turned it upside down and declared it as art - and just like that, the ‘Fountain’ was born.

The exhibition he submitted it to was held by the Society of Independent Artists, which was one of the most liberal and revolutionary artist societies in New York. The exhibition ignored all social stigma and political authorities that were prevalent at the time against the oncoming of modern art, there was no judgement or awards and anyone who paid money could exhibit their work. But when the ‘Fountain’ was submitted for the exhibition, no matter how radical the society thought they were, they couldn’t accept it as an artwork. The statement the board of directors issued in response to the submission of Mr. Mutt’s ‘Fountain’, was - “The Fountain may be a very useful object in its place, but its place is not an art exhibition, and it is, by no definition, a work of art”. Duchamp, who was a board member of the society himself, resigned shortly after.

The news about the independents who claimed to be an open society in the art world rejecting an artist’s work quickly started to stir up the masses. Soon an inevitable question had to be asked - if not this then ‘what is art?’ and ‘who decides what art is?’. This simple question was the beginning of contemporary art.

Why does Macel Duchamp matter to us now?

Physicist, Kim Sang Wook explained it better than I ever can, when he said:

“Despite the invention of photography, artists could still survive. Duchamp was saying that they could just call photographs – photographs, and call the works created by human beings art. He was saying we could be saved by the human ability to give things meaning. This may seem like a little sophisticated, but here's why it's not. We watch the Olympics and passionately cheer for people running races. This is a funny thing because from the perspective of an AI-era machine there are plenty of machines that move faster than a human. If a human being were to race against a machine, the human being would definitely lose. So, is it necessary for a human to keep working on processes to become faster than a car? That would be foolish. People race against one another, and we divide the races into categories like the 100m. Then we give a prize to the one who runs fastest in that category. How could there be meaning in such a thing? No, we're going to imbue it with meaning. Those people are winners at the Olympics, dividing winners from losers is like dividing art from non-art. We will pay them for the rest of their lives. They will go down in history as bringing glory to their nations. Duchamp is saying you just have to decide this. But, in an age where we live amongst machines and need to compete against them, the way to survive is through the power of imagination and our ability to give meaning.

I think we’ve already started moving to an era where, the purpose of human is to be the creator (I know, I hear it too). But what I mean is, in some ways if you think about it, it may have always been our purpose, even as children I remember being the happiest when I was making something that was mine, whether it was shitty sandcastles or cardboard people. But somewhere when we grew up, a job became our job and to create was to recreate. We’re already seeing a surge in people moving away from day jobs to content creation, what happens to the world if all of us did that in some form? Chaos, probably.

To think, to communicate, to ideate, to make mistakes and create randomness, to be a human - maybe that’s what the jobs of the future would look like for everyone. Who knows.

Either way, pulling the same thread of the timeline from the history of cameras and laying it along our current timeline, I would probably guess that our AI revolution is still waiting for our Kodak moment. We’re still in a place where we can take solace in knowing that the technology is still not good enough to actually replace us at our jobs, at least not yet. We take comfort in long reddit threads that breakdown the bugs and discrepancies in every new AI. The only problem is, our timeline is on steroids, you see, what happened in a hundred years will most definitely happen in less than 20 years today. Our Kodak moment could be tomorrow. And when it happens, I think we should ask ourselves - What would Marcel Duchamp do? How would we break everything we know and start creating?

P.S: I tried to fact check as much as I can, if you have any opinions you don’t agree with, feel free to DM me like ‘Actually…’. I can take it.

Thanks for reading The Loop! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Like this project

Posted Sep 14, 2024

Reviewed OpenAI's Sora AI and its impact on media and art, exploring how, amidst rapid technological change, Duchamp’s legacy can inspire future creators.

Likes

0

Views

24

Tags