Soundtrack to the Seasons

Like this project

Posted Apr 17, 2024

Feel like giving each season a personal playlist? This handy guide to keeping the classics with you all year round can help.

Likes

0

Views

7

Tags

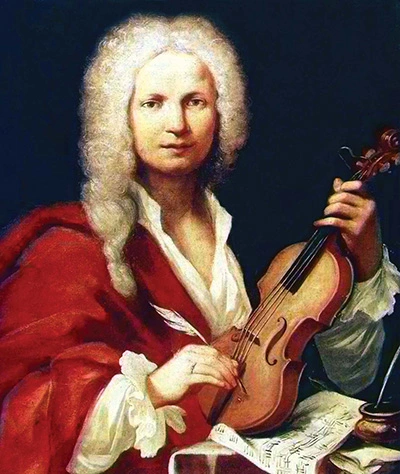

Vivaldi: The Man for All Seasons

A painted image of composer Antonio Vivaldi. Vivaldi holds a violin in his left hand and a writing quill in his right hand; the violin rests on top of a sheet of music notations and next to an ink jar.

Before we look at each season individually, let’s pause to consider one of the few classical pieces that was bold enough to tackle all of them in one go: Antonio Vivaldi’s set of four baroque concertos best known as the Four Seasons.

In Four Seasons, winter, spring, summer, and fall each get their own concerto composed for a violin soloist, a group of string instruments, and a keyboard. Concertos were Vivaldi’s specialty—works in three movements, usually written for one solo instrument and a backup ensemble.

What makes Four Seasons so special, however, isn’t its size (twelve movements total!); it’s that it manages to tell a story and capture specific scenes without the help of words…kind of like a musical painting. What’s the big deal, you ask? The big deal is that this was a pretty new concept in Vivaldi’s day. Before Vivaldi, purely instrumental music rarely had a story blueprint or “program” to go along with it.

What’s even more of a big deal is that Four Seasons helps you create some incredibly “detailed” mental pictures by casting certain instruments as “characters” or as elements of nature. Hear those trills (i.e., vibrating sounds) from the violin in Spring? Those are meant to be birds singing in springtime. That rumbling in the cellos in Winter? That’s supposed to represent a winter storm.

Vivaldi - Concerto No. 1 in E major,

“Spring” (La primavera), I. Allegro

Vivaldi - Concerto No. 4 in F minor,

“Winter” (L’inverno), I. Allegro non molto

Oh, and as if that weren’t enough, each concerto occasionally inserts a ritornello (a musical “refrain” that repeats over and over, pronounced ree-torn-EL-oh) that helps listeners settle into the general sentiment of the season. For example, Spring’s famous refrain is upbeat and “joyous,” while Winter’s characteristic ritornello is furious and forceful.

Spring: Here comes the sun…

A cropped illustration of the personification of Spring, a white woman with blonde hair holds her clasped hands against her shoulder with her eyes closed, suggesting a calm energy.

Rise and shine and get ready for these spring-themed works designed to evoke thoughts of new beginnings and endless possibilities. From the gentle and graceful to the powerful and exciting, these works, like the season they represent, are full of expectation and inspiration. So jump-start your ears with these sometimes bright and breezy, sometimes riveting and relentless bits of music…and be sure to listen for musical illustrations of seasonal sounds like singing birds or rolling thunder along the way.

Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Movement 1: “Dawn” by Edvard Grieg

A photograph of the setting sun against a sky with brushstrokes of clouds. The horizon is lined with the silhouettes of building tops.

Grieg - Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Movement 1: “Dawn”

This interlude by Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg comes from a much larger work based on a play by fellow countryman Henrik Ibsen. The famous and, as author H.T. Finck notes, “exquisitely beautiful” melody—constantly used in cartoons to suggest a bright sunny day—moves gently up and down the musical scale, sort of like a light spring breeze. Listen for the little trills played by the flute that sound like birds chirping.

“Variations on a Shaker Hymn” from Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland

A photograph in which a small white house is set in a green field with white flowers in the foreground and green trees on the photograph’s left and right edges. Behind the small house is a white fence and a very large red building.

Copland - “Variations on a Shaker Hymn” from Appalachian Spring

American composer Aaron Copland chose the familiar Shaker tune “Simple Gifts” (or “’Tis the Gift to Be Simple”) as the basis for this section of choreographer Martha Graham’s ballet, Appalachian Spring. In doing so, Copland gave the song a sweeping and majestic reinterpretation, allowing it to pass through different instruments at different speeds. Meant to evoke a “celebration in spring…in the Pennsylvania hills,” this movement begins with a clarinet solo and grows steadily into a forceful statement for the entire orchestra. Written in a cheerful major key (i.e., specific set of notes), this extra forte (loud) moment suggests the glorious “optimism and hope” often associated with spring.

Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major, “Spring” by Robert Schumann

A photograph of daisies taken from a low angle. The sunlight from a clear blue sky overhead makes the undersides of the flowers translucent.

Schumann - Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major, “Spring”

Robert Schumann said he wanted the opening moments of this bold and exciting symphony to “sound…like a call to awaken” his listeners. And does it ever. If you thought the noises of spring were simply soft and lilting, think again. In his “Spring” symphony (based on a poem about the season and, perhaps, inspired by Schumann’s own happy marriage), Schumann captures the joy and anticipation that go hand in hand with the arrival of spring by infusing his music with lots of syncopation (notes that don’t fall on a steady beat and leave you feeling a little off-kilter). Expect some heart-pounding percussive passages and electrifying calls from the brass instruments in this brilliant ode to the season of “new life.”

Symphony No. 6 in F Major, “Pastoral” by Ludwig van Beethoven

A photograph of a flock of sheep grazing in a wide-open green pasture with a cloudy blue sky and forest-covered hills in the distance.

Beethoven -Symphony No. 6 in F Major, “Pastoral”

Symphonic master Ludwig van Beethoven was a huge fan of the countryside and this piece—complete with musical representations of dancing shepherds, rumbling thunderstorms, and babbling brooks—can be heard as one big love letter to nature. Be careful not to take anything for granted as you journey through Beethoven’s tour of the country; little moments (like a small flute solo at the end of movement 2) can build and develop until they become massive themes (like the thrilling tune in the final movement).

Music for Spring Holidays

Easter

Intermezzo from Cavalleria Rusticana (Rustic Chivalry) by Pietro Mascagni

This brief but beautiful instrumental piece acts as a peaceful intermission in an otherwise violent and tragic opera that takes place entirely on Easter Sunday.

Russian Easter Festival Overture by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov

Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov’s musical depiction of an Easter service features everything from the “call and response” of typical church chants (represented by solo “calling” instruments and larger “responding” instrument ensembles) to the bustling spring celebrations that follow Easter mass.

Messiah by Georg Frederic Handel

Though usually heard at Christmastime, much of Handel’s famous work—particularly the familiar “Hallelujah!” chorus—deals with the Biblical account of the events of Easter.

Passover

Israel in Egypt by Georg Frederic Handel

This often dark and mysterious piece for voices and orchestra portrays the suffering and eventual triumph of the Old Testament tale of Passover. Try listening to “He Sent a Thick Darkness” for a frightfully atmospheric picture of a shadowy Egypt, then switch to “Sing Ye to the Lord” to relieve your ears with some brighter, happier music.

Now on to the sizzling days of summer…

Summer: …And the livin’ is easy

A cropped illustration of the personification of Summer, a white woman with dark red hair reclines with her left arm behind her head. A big sunflower is partially visible behind her head.

Classical music for the summer season is often as laid back and relaxing as your typical day at the beach. Mostly sweet and soothing, the following summer pieces tend to repeat the same melodies and themes over and over, making time seem like it’s standing still—kind of the same way a swelteringly hot afternoon can seem to go on and on forever. Keep your ears open for lots of solos from the wind instruments, whose soft and syrupy sounds may just send you off into a blissful summer night’s dream.

Three Small Tone Poems: I. Summer Evening by Frederick Delius

A photograph of a field with trees in the background and tall grass and ferns in the foreground. There is a lens flare on the left side of the picture from the sun.

Delius - Three Small Tone Poems: I. Summer Evening

British composer Frederick Delius’s take on a summer’s night is perfect hammock music. In fact, the main theme, with its gentle syncopation, seems to actually sway back and forth in hammock fashion. Plus, Delius’s music unfolds in long, slow, sustained phrases (a stylistic trick known as legato, pronounced leh-GA-toh) without any real breaks or musical rests. This relaxed movement from note to note might remind you of a lazy evening during a summer heat wave.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Overture, Op. 61 by Felix Mendelssohn

A cropped version of a painting by Sir Edwin Landseer. A woman in a white gauzy dress and floral crown leans into someone who has a person’s body and a donkey’s head, which also wears a floral crown. Fairies and white rabbits surround the pair.

Mendelssohn - A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Overture, Op. 61

Mendelssohn’s relatively short homage to Shakespeare’s comedy (not to be confused with the much longer piece written as a kind of soundtrack to the entire play) is often as “dreamy” as a hazy summer’s evening thanks to some lovely and lilting music from the wind instruments. But don’t get too comfortable—Dream also includes some incredibly bouncy and fanciful tunes designed to evoke the hilarious misadventures of the forest fairies, star-crossed lovers, and clumsy theater troupe members that make up Shakespeare’s story. If you’re familiar with the play, you might recognize some of those huge leaps in the violins as being an imitation of donkey noises.

Prélude a l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the afternoon of a faun) by Claude Debussy

A photograph of a mischievous-looking half-man, half-goat statue playing a pan flute in a forest.

Debussy - Prélude a l’après-midi d’un faune

Ever get the feeling when it’s very hot outside that you have trouble thinking straight? Like you’re walking through a fog? This well-known Debussy piece captures some of that sensation by introducing small bits of winding melody that drift aimlessly along and never really go in a “straight” or obvious direction. These fragmented tunes—often played by the flute, clarinet, or oboe—are frequently surrounded by a lot of trembling (or tremolo, TREH-moh-loh) effects from the strings, which create a sleepy atmosphere similar to a hot and humid summer day.

Music for Summer Holidays

The Fourth of July

The Stars and Stripes Forever by John Philip Sousa

It’s simply not a Fourth of July celebration without this quintessentially American piece from the man known as the “March King.” Its trademark “big-band” flavor is so lively and exciting, it never fails to get audiences in a patriotic mood.

1812 Overture by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Though its Russian history has nothing to do with the Fourth of July, the 1812 Overture—a tour-de-force that includes actual canon fire and tons of crashing cymbals—goes really well with fireworks.

Labor Day

Fanfare for the Common Man by Aaron Copland

Copland’s World War II-era piece was designed to honor anyone and everyone in the American workforce. Though fanfares (showy pieces for brass instruments) were usually reserved for royalty or heads of state, Copland broke with tradition and wrote one for the everyday American, whom Copland felt “deserved” a musical celebration.

Had enough of the heat? On to fall…

Fall: All the leaves are brown...

A cropped illustration of the personification of Fall, a white woman with red leaves in her black hair smiles and looks towards the viewer.

Warm and welcoming one minute, chilly and foreboding the next, these works are as fickle and unstable as the fall season. As you listen, be on the lookout for music that’s constantly shifting (from loud to soft, high to low, etc.) and leaves you feeling a little unsteady. While you’ll hear plenty of wind instruments here, expect some melancholy music from the strings as well. Their sorrowful sound is often the composer’s way of reminding you that cold weather is approaching and the year is coming to an end.

Academic Festival Overture by Johannes Brahms

An exterior photograph of a brick academic building from its upper floor to the blue sky above it.

Brahms - Academic Festival Overture

It’s back-to-school time! Get yourself ready for class with this piece by German master Johannes Brahms, written when he received an honorary university degree in 1880. Brahms clearly thought school should be as much about fun as it was about study. The piece begins with a disciplined “march” that calls to mind intense lectures and serious homework sessions, but soon bursts into a fast and furious celebration of the school year, full of crashing cymbals and borrowed snippets of traditional student songs. (Watch out for the ever-popular “Gaudeamus Igitur”––a familiar European school song––at the tail-end of the piece).

Autumnal Sketch by Sergei Prokofiev

A photograph of autumnal leaves layered on each other on the ground.

Prokofiev - Autumnal Sketch

Though 20th-century composer Sergei Prokofiev didn’t give this piece a title until after it was completed, you’ll probably agree that the name fits. Like the autumn weather itself, Prokofiev’s Sketch is often wild and unpredictable—full of dissonance (a musical phenomenon that purposely places “clashing” notes beside one another to disturb the ear) and contrast. Listen for moments when groups of instruments seem to be fighting one another by moving in different directions (for example: the lower strings often move down the scale, while the violins slide upward). This kind of musical tension is more than appropriate for the fall where temperatures (and colors) are constantly changing.

Poema Autunnale (Autumnal Poem) by Ottorino Respighi

A photograph featuring a big tree with orange and yellow leaves on its branches and the ground underneath it. Other green trees are visible behind it further in the park setting.

Respighi - Poema Autumnale

It’s a safe bet that Italian composer Ottorino Respighi thought of fall as a time for solitude. Loneliness seems to be the general theme of Poema, possibly because most of the work is all about instrumental solos, particularly solos for violin (a go-to instrument for composers when they want their music to sound extra solitary and emotional). Though this piece does feature a dance-like interlude for the entire orchestra that may have you tapping your toes for a moment or two, the majority of the music follows a single violin as it twists and turns in a sorrowful minor key. This lends the work a melancholy feel that’s perhaps fitting for the season of shorter days and long chilly nights.

Music for Fall Holidays

Yom Kippur

Kol Nidrei by Max Bruch

A hauntingly beautiful piece based on the Judaic prayer (usually sung by the cantor, the musical leader of synagogue prayers). Composed for cello solo and orchestra accompaniment, this lush version of the traditional melody is heard during evening services for Yom Kippur, also known as the Day of Atonement, and can serve as one of the three repetitions of the sacred chant.

HALLOWEEN

Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Movement 4: “In the Hall of the Mountain King” by Edvard Grieg

Revisit Peer Gynt in the fall with this famous movement, often used in cartoons when somebody is sneaking up on somebody else. It doesn’t get much creepier than Grieg’s pulsating tune, full of plucked strings and extremely low woodwinds.

Toccata and Fugue in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach

Though this work for organ has no accompanying story or “program,” listeners all seem to agree there’s something rather eerie about it. That’s perhaps because of its unsettling minor key, its use of chromatics (successive notes that sit so close together they sound jarring or upsetting), and the almost demonic speed and agility that are needed to play a toccata (from the Italian word for “to touch,” pronounced toh-CAH-tah) and fugue (a complex and elaborate version of a musical round).

Danse Macabre (Macabre Dance) by Camille Saint-Saëns

A bone-chilling musical journey through a graveyard at midnight, this spooky dance of the dead features a devilish violin and some frightening music for the xylophone (meant to represent skeletons!).

Night on Bald Mountain by Modest Mussorgsky

You won’t find anything more Halloween-y than this ultra scary symphonic piece, originally meant to depict a “witches’ gathering” but immortalized for modern audiences by a super spooky segment in Disney’s Fantasia. Listen for a supernatural call and response between different musical themes and instruments, particularly the jerky and disjointed tunes from the strings (which represent the witches) that play against the slower, more terrifying theme for the brass (which represents the devil).

Veterans Day

War Requiem by Benjamin Britten

British anti-war composer Benjamin Britten wrote this variation on the traditional Latin requiem in the aftermath of World War II, but much of its lyrics are taken from poems written by a young soldier during World War I (the original inspiration for Veteran’s Day). Britten’s clever use of violent percussive sounds often make you feel as though you’re on a battlefield, and are a painful reminder of the horrors of war. There are also plenty of softer, more poignantly beautiful moments in this tribute, which help make it appropriate listening for a day of remembrance.

And now to round out the year with winter…

Winter: Let it snow…

A cropped illustration of the personification of Winter, a white woman with blonde hair peeks at the viewer around the edge of her cloak’s hood.

Don’t let the cold get you down. These composers sure didn’t. On the contrary, they knew that winter was just as full of intrigue and adventure—think winter vacation!—as it was of snow and ice. While these pieces feature occasional slow-rhythm moments of sadness and reflection (let’s face it, who doesn’t feel just a little bit gloomy when the year draws to a close?), they’re also pretty lively and action-packed. Expect lots of impressive sound effects from instruments like the flute, the violin, and the piano as these composers do their best to call to mind blistering winds, slippery patches of ice, and delicate snowfalls.

Symphony No. 1, “Winter Daydreams” by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

A photograph of a row of bare trees in a snowy field. The sun peeks through the trees, casting their shadows on the snow.

Tcahikovsky - Symphony No. 1, “Winter Daydreams”

From the first moments of Tchaikovsky’s “Winter Daydreams” symphony, with its shimmering violins and whistling flutes, listeners know they’re in for quite the sleigh ride. Be sure to hold on tight as the famous Russian musician takes you through all sorts of emotional winter “journeys”—from a bustling trek in the snow, to a sorrowful drive through a dismal and “shadowy” landscape, and beyond. Be warned: Tchaikovsky often jumps from one musical idea to another very quickly (a pretty risky move in his day) in an effort to shake things up and explore a variety of feelings. This symphony may make you want to laugh and cry over the space of just a few minutes.

Excerpts from “The Frost Scene”: “What power art thou…?” & “See, see, we assemble” from King Arthur by Henry Purcell

A close-up photograph of clusters of snow and ice on tree branches.

Purcell - Excerpts from “The Frost Scene”

Though not based on the typical King Arthur legend (no Lancelot or Guinevere here), Henry Purcell’s opera still features plenty of magic and intrigue. In this “Frost Scene,” one of Arthur’s enemies transports the action to a freezing snowscape, and we listen as the local people (headed by a grumpy winter spirit sung by a bass vocalist), lament the bitter cold. Purcell paints a vivid picture of the scene by having the instruments and singers perform almost exclusively in short, choppy notes (known as staccato, stah-CAH-toh) that mimic shudders and shivers. In fact, Purcell often has his chorus and soloist sing one word over several quick notes to emphasize the frozen climate, as when they sing, “co-o-old.” Sounds as though they’re actually shaking in the snow, doesn’t it?

Children’s Corner: IV. “The Snow is Dancing” by Claude Debussy

A photograph of thick snowflakes falling around several snow-laden trees.

Debussy - Children’s Corner: IV. “The Snow is Dancing”

One of six small piano pieces that composer Debussy dedicated to his young daughter, “The Snow is Dancing” sounds just as its title suggests: like a walk through a light snowfall. Debussy was a highly accomplished impressionist (a word music scholars use to describe composers skilled at giving the “impression” or general feeling of a scene), and this piece is a perfect example of his style. The soft, swirling melodies give the effect of snowflakes “dancing” on a gust of wind.

Music for Winter Holidays

Christmas

The Nutcracker by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Sugar-plums literally dance in this fanciful classical music favorite, which follows the adventures of a young girl and her enchanted Christmas toy. Winter and snow inspire several of the many dances that make up this famous ballet, especially the “Waltz of the Snowflakes” and “The Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy.”

Messiah by Georg Frederic Handel

Though we suggest you have a listen to this work around Eastertime as well, Messiah is also a beloved Christmas classic. Many of its celebrated choruses, such as “For Unto Us a Child is Born,” were written specifically for the winter season.

New Year’s Day

“Prelude” from Also sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss

German composer Richard Strauss’s “overwhelming” work, though originally an homage to a contemporary philosopher, is often used to symbolize new beginnings. Its dramatic main theme, which features slowly rising trumpets and a few crashing chords for the whole orchestra, will help start your new year with a (very big) bang.

Music for Royal Fireworks by Georg Frederic Handel

Why not pair your New Year’s celebration with some music that was actually meant to go along with fireworks? Handel’s explosive piece, written in celebration of a European peace treaty and skillfully composed to feature a booming timpani and some flashy brass instruments, is a great way to ring in the New Year.

Valentine’s Day

Romeo and Juliet Overture by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

You know those sappy scenes in movies, TV shows, and commercials where two people run to each other from across an open field? Nine times out of ten, this is the music that’s playing in the background. Tchaikovsky’s musical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is the ultimate romantic piece, built around a sweeping love theme that’s been making listeners swoon for generations.

Barcarolle (“Belle nuit” or “Beautiful night”) from Les Contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann) by Jacques Offenbach

This barcarolle (or “boating song”), with its gently swaying melody and dreamy lyrics about love and happiness, is a perfect Valentine lullaby. The voices are the stars here, but keep your ears open for the flutes and cellos, which also play a big role.

Prelude from Tristan und Isolde (Tristan and Isolde) by Richard Wagner

Sometimes if you want a good love story, you have to turn to tragic opera. These opening notes from Wagner’s infamous Tristan und Isolde are about as bittersweet and full of tension as music can get, thanks to Wagner’s trick of never quite fitting his love theme into a conventional musical key—a move which is bound to make you feel a little confused and disoriented. Maybe not the happiest of Valentine’s Day tunes, it will certainly leave an impression.

President’s Day

Lincoln Portrait by Aaron Copland

This powerful tribute to the 16th U.S. president features an ear-pounding central melody that’s as imposing as the towering 6′4″ Lincoln himself. The piece packs extra emotional punch by including a spoken narrator who recites excerpts from Lincoln’s speeches.

An illustrated image of a tree whose leaves are divided into four sections to colorfully represent each season of the year.

Now that you’ve gotten through the year, try listening to these pieces all over again…or come up with some new seasonal lists of your own. As you’ve seen, there’s plenty of classical fun to be had from January to December.

Writer

Eleni Hagen

Editors

Lisa ResnickTiffany A. Bryant

Producer

Kenny Neal

Updated

Works Cited

Arundell, Dennis. Henry Purcell, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press Publishers, 1927.

Brown, David. Musorgsky: His Life and Works. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. Copland Since 1943. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

Finck, H.T. Grieg and His Works. New York: John Lane Company, 1909.

Kennedy, Michael. Richard Strauss: Man, Musician, Enigma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Lee, M. Owen. Unlocking the Masters: The Great Instrumental Works. Pompton Plains, NJ: Amadeus Press, 2005.

Lockspeiser, Edward. Debussy: His Life and Mind, Vol. I. New York: Macmillan Co., 1962.

Lunday, Elizabeth. Secret Lives of Great Composers. Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2009.

Machlis, Joseph and Kristine Forney. The Enjoyment of Music: Shorter Version, 8th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1999.

Smith, Tim. The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Classical Music. New York: Perigee, 2002.

Walker, Alan, ed. Robert Schumann: The Man and His Music. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 1972.

Weinstock, Herbert. Tchaikovsky. New York: Da Capo Press, 1980.

Sources

Abraham, Gerald, ed. The Music of Tchaikovsky. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, Inc., 1969

Bierley, Paul E. John Philip Sousa: American Phenomenon. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1973.

Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music. New York: Pegasus Books, 2007.

Butterworth, Neil. The Music of Aaron Copland. London: Toccata Press, 1985.

Dean, Winton. Handel’s Dramatic Oratorios and Masques. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Dubal, David. The Essential Canon of Classical Music. New York: North Point Press, 2001.

Frisch, Walter. Brahms: The Four Symphonies. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Fry, Stephen. Stephen Fry’s Incomplete & Utter History of Classical Music as Told to Tim Lihoreau. London: Pan Books, 2005.

Gilliam, Bryan, ed. Richard Strauss and His World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Henkel, Kathy and Carolyn Hove. “Academic Festival Overture.” Program notes for Los Angeles Philharmonic (online “Philpedia” source)

Horton, John. The Master Musicians: Grieg. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1974

Kennedy, Michael. The Master Musicians: Britten. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1981

Lockspeiser, Edward. Debussy: His Life and Mind, Vol. II. London: Cassel & Company, Ltd., 1965.

Lockspeiser, Edward. The Master Musicians: Debussy. New York: Ferrar, Straus and Giroux, 1963.

Lyle, Watson. Camille Saint-Saëns: His Life and Art. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. and New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1923

Mann, Alfred. Handel: The Orchestral Music. New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

Nestyev, Israel V. Prokofiev. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1960.

Palmer, Christopher. Delius: Portrait of a Cosmopolitan. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., Ltd., 1976

Poznansky, Alexander. Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man. New York: Schirmer Books, 1991.

Respighi, Elsa (arranged by). Ottorino Respighi: His Life Story. London: Ricordi, 1962.

Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay Andreyevich. My Musical Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1942

Sousa, John Philip. Marching Along: Reflections of Men, Women and Music. Boston: Hale, Cushman and Flint, 1928.

Steinberg, Michael. Notes to TELDEC recording of Britten’s War Requiem, 1998. (New York Philharmonic, Kurt Masur)

Todd, R. Larry, ed. Mendelssohn Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Todd, R. Larry, ed. Schumann and His World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Eric Friedman

Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal

Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant

Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee

Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors

Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at digitallearning@kennedy-center.org.