COVID-19 Exposed Domestic Violence Issues, Now What?

At the beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic lockdown, the United States saw an exponential rise in calls into Domestic Violence Hotlines.[1] Unfortunately, with governors calling for people to “shelter in place,” there was no way for people to leave their situations. Domestic Violence shelters were shuttered, and for the few that remained open, people were left with the options of potentially contracting the virus or staying with their abuser. An impossible decision. I knew that in the United States, our approach to Domestic Violence was reactionary, but this pandemic desperately highlighted the need to become more preventionist.

As a law student at CUNY School of Law, I have focused my education on family law with an emphasis on domestic and gender violence. I also am involved in the Courtroom Advocacy Project, where, under the supervision of an attorney, law students help individuals write order of protection petitions and then follow the case, attending future court appearances. There, I see firsthand how people are affected by domestic and gender violence. I also have a unique perspective because I am a survivor of domestic violence myself.

As I saw the numbers in domestic violence hotlines rise in March, and then drop ominously in the beginning of April as everything remained closed, it brought to light the faults within our system. Our shelters are good, the support we offer victims and survivors is good… but we need a plan so that people do not need to seek out these types of resources, because what happens when people are in lockdown, or simply afraid, and unable to seek them out?

I have always felt that education would be the way to stomp out domestic violence, but historically, domestic violence prevention programs don’t work. For one, they are often court mandated after violence has already occurred. In January The Atlantic published an article about the “Duluth model.” This evidence-based model has seen great success responding to victims of domestic violence and reeducating abusers.[2] The Duluth model[3] is addresses the idea that domestic violence is rooted in the patriarchy, that men have been conditioned to maintain power over women by any means necessary. Designed similarly to the 12-step program of say, Alcoholics Anonymous, it encourages abusers to articulate the things they have done in order to release the stigma around it while in a “safe space.” To illustrate how one partner obtains and sustains power over the other, the Duluth model uses a “Power and Control Wheel.” But the wheel only shows the pattern of abuse, not the root cause, and because of that, it is becoming increasingly more controversial.

A few months ago, I attended a family law panel held at CUNY Law, discussing the future of the industry. During the Q&A, I asked the panel of attorneys what they felt about transformative justice within the realm of domestic violence. How do we fundamentally change people and heal families without involving the court system. This can be an extremely traumatizing process for all parties. I was directed toward the work of Donna Coker, a leader in the field of transformative justice and domestic violence. In an article, Coker suggests the social shaming of abusers, and then unconditional acceptance. Her argument was that the shaming would prevent the abuser from acting again, and it would deter future abusers, but the ultimate acceptance would make them feel comfortable to be among society. She thought that these extremes would be powerful enough to change behaviors.

But something about this did not sit well with me. Shaming a person for bad behavior is a recipe for disaster, because shame often erupts as another emotion, such as anger, and can lead to self-harm or abusive behaviors. It seemed like an idea that would perpetuate the Power & Control Wheel, not deflate it.

Turns out I wasn’t wrong. Brene Brown, professor, author, and social worker, is a leading researcher of shame. She has devoted many of her books to the subject, and how vulnerability can be the antidote for shame. Similar to the Duluth model, her idea is that in order to overcome shame, you need to name it. Being vulnerable with other people and sharing the things that make you experience the most shame open the lines of communication and allow us to connect at a deeper level. In short, it promotes empathy.

I understand where Donna Coker is coming from by suggesting we shame abusers, because if your ultimate goal is to get humans to connect with one another, we need to facilitate vulnerability. But shaming a person for bad behavior is not the answer, because often times abusers are also victims, just not the victim in this particular room. Ultimately, you’re shaming a symptom of a larger, deeper rooted issue. It’s like blaming the tip of the iceberg for the sinking of the Titanic. It was the ice underneath the water that ripped holes and caused it to sink, the ice on top was just the indicator that the iceberg was there. This is how shame works.

What I am suggesting is that we start using people’s shame and subsequent behaviors or moods to direct us to where the issues are, where they need the most healing. By healing the individual, we can heal families. I believe the bridge to healing is going to be socio-emotional literacy. We need to provide people with the tools to communicate their emotions and moods.

Emotional literacy involves self-awareness and understanding our own feelings. It requires education, because so many of us only have the language for what Brene Brown calls the “Mad, Sad, Glad Club.” We can only articulate those three feelings, when really, emotions are far more nuanced.

On April 14 of this year, Brene Brown had Dr. Marc Brackett as a guest on her podcast entitled “Unlocking Us.” Dr. Marc Brackett is the founder of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, a professor within the Child Study Center at Yale, and recently published a book entitled “Permission to Feel.” During this episode, he discussed with Brene a program he designed in 2005, called the RULER approach.[4] RULER stands for Recognizing, Understanding, Labeling, Expressing, and Regulating emotions. Traditionally, it has been used in primary schools, and as I was listening to Dr. Brackett discuss the fundamental ideas of RULER, it occurred to me that this could be the answer to helping end domestic violence.

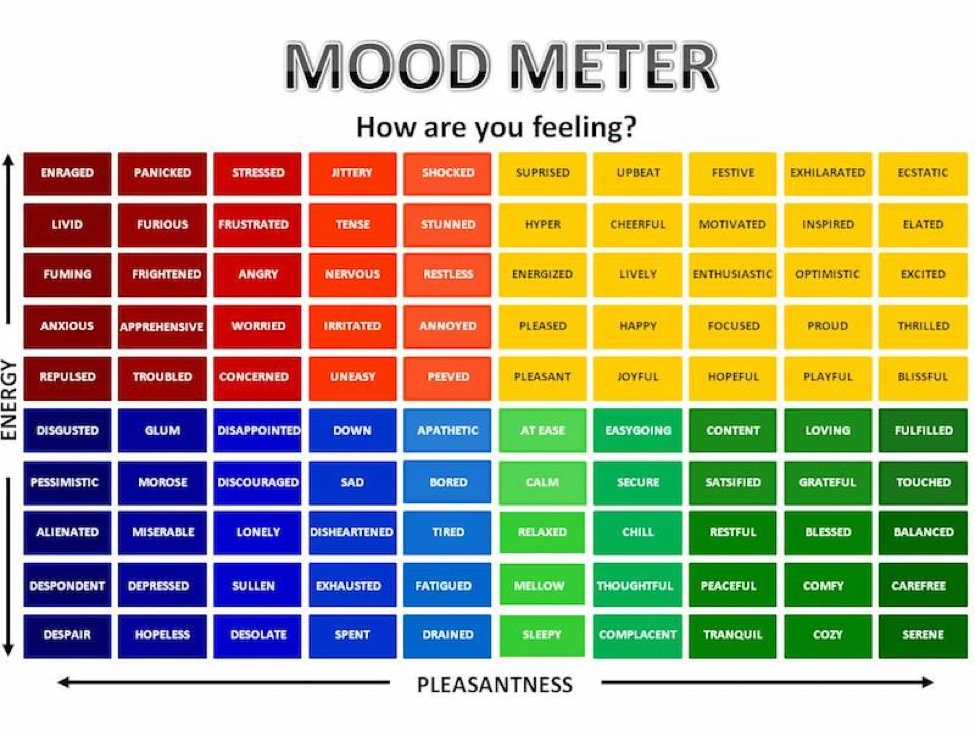

RULER uses a “Mood Meter,” by which an individual can point to or mark what word best describes what they are feeling. The feeling words are displayed on a colorful grid. Red feelings are high energy and more unpleasant. Blue feelings are low energy and more unpleasant. Green feelings are low energy and more pleasant, and yellow feelings are high in energy and more pleasant. These visual representations of feelings are the instruments by which RULER conducts their system. It forces people to pause, reflect and contemplate the nuances of their emotions. By giving people the tools to recognize, understand, label, express, and regulate their emotions, we are giving them the opportunity to communicate and express those feelings in a more healthy and constructive way.

Unsurprisingly, Dr. Brackett discusses how emotions point towards larger issues. Some examples of this are how anger is the feeling of perceived injustice. Jealousy is feeling threatened that you will lose something. Envy is wanting something that someone else has. Fear is the feeling of impending danger, and joy is the feeling of achieving a goal. People use violence when they have no other means of communicating, or when they don’t feel heard.

Emotional literacy also helps us become better listeners. By understanding our emotional innerworkings, we cultivate empathy because we can know that the other people in our lives also have complex feelings. When we understand our need to be heard, we are more likely to hear. In teaching RULER to individuals, we are also teaching people to become compassionate listeners, which is critical. Brene Brown states that our core human needs are to be seen, known, and loved, but how can you be seen, known, and loved, if you are not heard? This is why it’s crucial for the person who is sharing their internal emotions to have a compassionate listener to connect with.

Dr. Mark Brackett’s ideas around emotional literacy are based on the idea that we, as a society, need to start being preventionist, not interventionist, which is exactly my sentiment on domestic violence. If we teach emotional literacy at a young age, we create a society where people can freely communicate their feelings and emotions without using violence. Until RULER is an integrated part of our education system, I do think that it would be an excellent addition to how we approach abusers. Teaching abusers to connect with their emotions can prevent the use of force or violence within the home because they have the language and tools to be heard, seen, known, and loved.

Understanding ourselves is empowering. By helping people gain power and take control over their internal emotional world, they might be less likely to exert power and control over their partners, rendering the Power and Control Wheel obsolete. I am imagining a post-COVID world, where we realize the importance of becoming a preventionist society. I imagine if we start teaching emotional education, we might never be in a situation again where our domestic violence hotlines are ringing off the hook. I am imagining a world where the Mood Meter replaces the Power and Control Wheel, and that world has far more peaceful homes.

Like this project

Posted Nov 10, 2023

Researched, wrote, and edited this article.

Likes

0

Views

10

Clients

CUNY School of Law