New Mexico History: Biographical Timeline for Vicente Silva

Photograph of Vicente Silva, as published in "The Passing of Vicente Silva's Bandits" on Page 8 of the Jan. 15, 1899, edition of The Buffalo Courier.

Sometimes, it only takes a single record to set history straight. In this case, the record was for a baptism at Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Las Vegas, New Mexico.

This was the church that my father was baptized in, so I was expecting to see the Angel family name on quite a few of the records. But the one record that surprised me had the name of my grandfather’s grandparents as godparents of a child of one Vicente Silva and Telesfora Sandoval on Jan. 17, 1881. ("Enero 17 1881 bautice a Antonio nacido el 15, h. l. de Vicente Silva y de Telesfora Sandoval de Las Vegas. Padrinos Felipe Ángel y María Salazar. J. M. Coudert.” Page 466 of Our Lady of Sorrows church records previously posted by FamilySearch.org.)

Vicente Silva's name is perhaps one of the most despised in Las Vegas history. Charitably, he is often associated with a group of men known as “Las Gorras Blancas” (White Caps), a grass-roots self-defense organization that many non-Hispanic historians often label as “terrorists.” Not so charitably, he later led his own infamous group of bandits who were either suspected or convicted of carrying out numerous robberies and killings in the period between 1891 and 1893. In fact, Vicente was implicated in the hanging of Patricio Maes in October 1892, as well as the murder of his wife and her youngest brother, Gabriel Sandoval in 1893. In turn, he was murdered by his own gang members shortly after underpaying them for burying his wife in an arroyo near his hideout north of town. It took two years to find the bodies.

It’s clear that my grandfather’s grandfather, Felipe Ángel, was an unconvicted, but nevertheless close associate of Vicente Silva. After all, the role of “Padrino,” or godfather, is not one bestowed on someone lightly in Hispanic culture. A family legend conveyed to my father in the early 1970s seemed to try to hide this fact by spinning a tale that Felipe was some kind of black cowboy who arrived in New Mexico after being emancipated from a plantation in Louisiana. More accurately, he was a darker-skinned vaquero of mixed ancestral ("color quebrado") origin who rode with Vicente Silva in the 1870s, probably as far north as Wyoming, and returned to Las Vegas with him before the railroad arrived on July 4, 1879.

I’ve completed the first draft of a screenplay that tells Vicente Silva’s story from the perspective of my grandfather’s grandfather (as of November 2024, it still needs a lot of refinement), but I wanted to share here some of my research on Vicente Silva’s life in the form of a timeline, starting from the birth of his generation on a farm in Bernalillo, and finishing with the arrival of the railroad in Las Vegas, New Mexico, on July 4, 1879. (I’ll write a second biographical study later, covering the period of my screenplay that continues his life story through to its grim end.)

In some ways, Vicente’s life follows a similar arc to that of Walter White in the Breaking Bad television series, except of course, Vicente was a mostly illiterate redheaded Hispanic of the late 19th century who descended from the role of a legitimate saloon business owner to the brutal and paranoid head of a criminal enterprise, rather than a modern highly-educated high school chemistry teacher whose life spiraled downward into illicit drug manufacturing. But that difference pales in comparison to the fact that, unlike the well-crafted details of the stage upon which White, Jesse Pinkman, Saul Goodman, Gustavo Fring, and Mike Ehrmantraut played, Silva’s New Mexico Territorial world shaped a lot of what the state really is today.

Marriage of Antonio Abad Silva

and María Dolores Perea

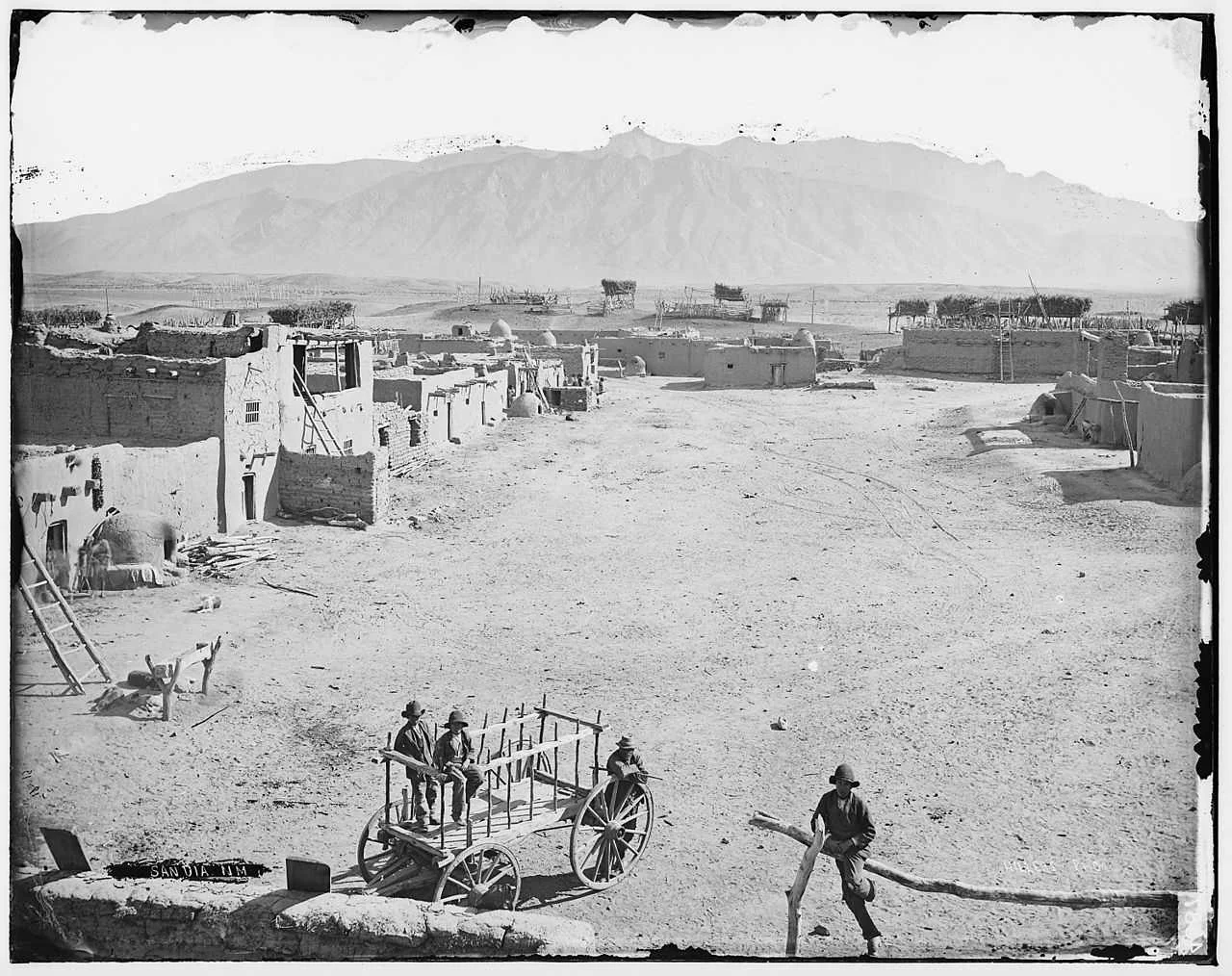

Sandía Pueblo in the 1880s, Photo by John K. Hiller via Wikimedia Commons.

The date of marriage for Antonio Silva and Dolores Perea is unknown, likely because two pertinent pages in the marriage registry for Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) Mission Church in Sandía Pueblo (the long-suffering church that served Bernalillo between 1751 and 1857) from just before the birth of the couple’s oldest child, Teodoro, are missing. The first absent page covered dates between Oct. 28, 1835, and Apr. 27, 1836, while the second covered the range between May 24, 1837, and Nov. 27, 1838. (Oct. 7, 1837, would have been the date 40 weeks before Teodoro’s birth date, near to when he would likely have been conceived.)

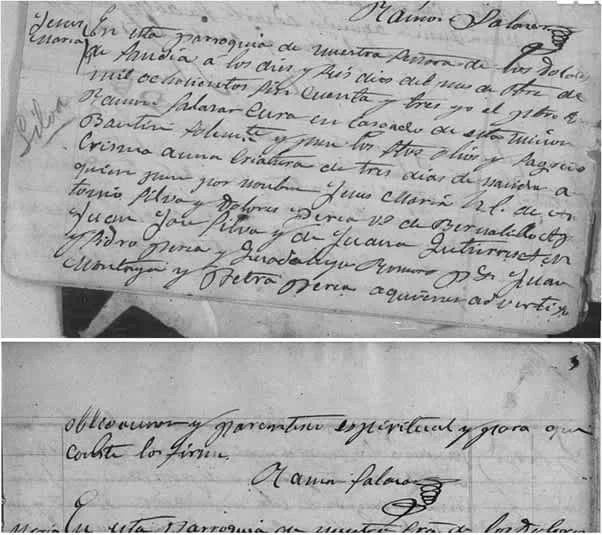

Juan José Silva and Ana María Lucero gave birth to Vicente's father, Antonio, according to Fray Antonio Chavez. He came into the world sometime in the 1810s. María Dolores was the daughter of Isidro Perea and María Guadalupe Romero, born in August 1816. Both ancestries can be traced back to the Spanish reconquest of New Mexico under Governor Diego de Vargas in the 1690s.

Vicente Silva’s older siblings

All children were baptized by Padre Fernando Ortiz at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores mission church in Sandía Pueblo:

Teodoro: Probably conceived October 1837 (roughly the time of the Chimayo Rebellion, which took place further north); born Saturday, July 14, 1838, in Bernalillo; baptized Sunday, July 22, 1838 (Page 259 of Sandía Baptism Book No. 35). His godfather was Hilario Perea

María Petra de Jesús: Probably conceived September 1840; born in Bernalillo shortly before her baptism on June 13, 1841 (age at baptism unrecorded, Page 310 of Sandía Baptism Book No. 35). Her godparents were Ramón Flores and Guadalupe Romero.

María Antonia de Jesús: Probably conceived March 1843; born in Bernalillo on Dec. 14, 1843, and baptized on Dec. 22 (Page 346 of Sandía Baptism Book No. 35). Her godparents were Blas Jaramillo and Jasinta Martines.

Vicente Silva’s birth

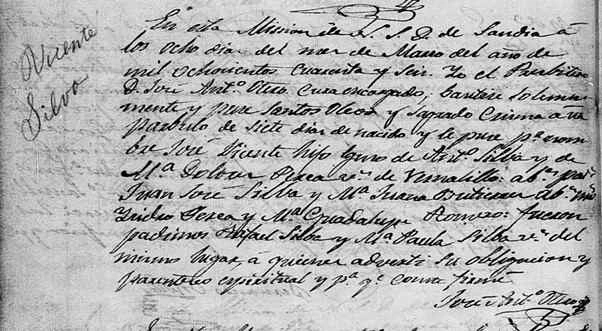

Baptismal Record of Vicente Silva. Page 385 of Sandia Baptism book No. 35, via FamilySearch.

Vicente was likely conceived in late May 1845 as tensions began to build between the United States and Mexico (following the American annexation of Texas two months earlier, that March).

(Events during this period included: José Antonio Laureano de Zubiría y Escalante, Bishop of Durango, visiting Sandía's mission church on June 7, 1845; Jose Antonio Otero replacing Fernando Ortiz as Padre of the mission church on Oct. 29, 1845; Manuel Armijo taking over New Mexico’s government from provisional governor Jose Chavez y Castillo for the last time on Nov. 16; and a small land war erupting in nearby San Pedro, a mining community to the east late in 1845. After these events, all eyes turned eastward to the events in Texas by the end of winter in March 1846.)

María Dolores Perea went into labor and gave birth to Vicente Silva on Sunday, Mar. 1, 1846, according to his baptismal record. Before she and her husband Antonio Silva had him baptized the next Sunday, American and Mexican troops engaged in southern Texas, marking the start of hostilities between the two countries (likely, the news wouldn’t have reached them until after war was declared on May 13). Antonio’s younger brother and sister, Rafael Silba and María Paula Silba (wife of Julian Rael), served as godparents. The new Padre José Antonio Ortiz carried out the ritual.

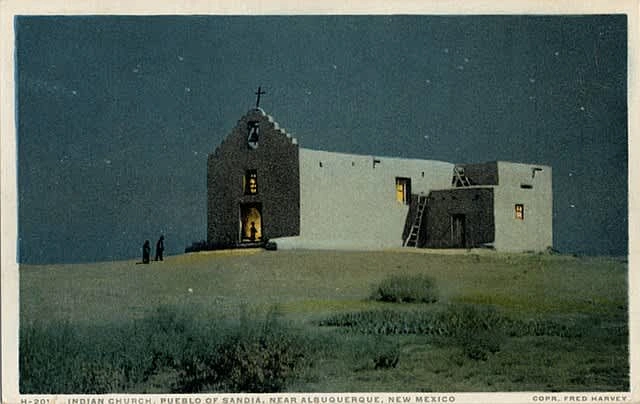

Nuestra Señora de los Dolores Church in Sandía on a Fred Harvey series postcard. The church was already in bad shape in the 1860s, and was eventually replaced by St. Anthony Catholic Church at Sandía Pueblo. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Extended family at Vicente's time of birth

On his father’s side (Silva),

Vicente had the following aunts and uncles:

María Dolores, age 41, wife of Domingo Mora

Francisca Paula María Ygnacia, age 35, wife of Julian Rael (Vicente’s godmother)

María Juliana, age 33

Still living with grandparents Juan José Silva (in his 60s) and María Juana Gutiérrez (age 58):

José Rafael, age 26 (Vicente’s godfather)

Manuel, age 20 (will marry Juana Dorotea Romero up in San Miguel del Vado in 1851)

José Francisco, age 19 (will marry Margarita or María Paula Lucero)

Jesús María, age 17 (will marry María Feliz Gutiérrez)

Juan Cristoval, age 13 (will marry first María Rosalia Romero, then María Merced Gallegos, and then a third wife – name unknown)

On his mother’s side (Perea),

Vicente had the following aunts and uncles:

Pedro José, age 32

José Julian, age 27, husband of Dolores Martínez

María Guadalupe, age 25, wife of Juan Geronimo Marcial Montoya

Still living with grandparents Ysidro Antonio Perea (age 53) and María Guadalupe Romero (age 52):

José Domingo, age 20

The war with the United States

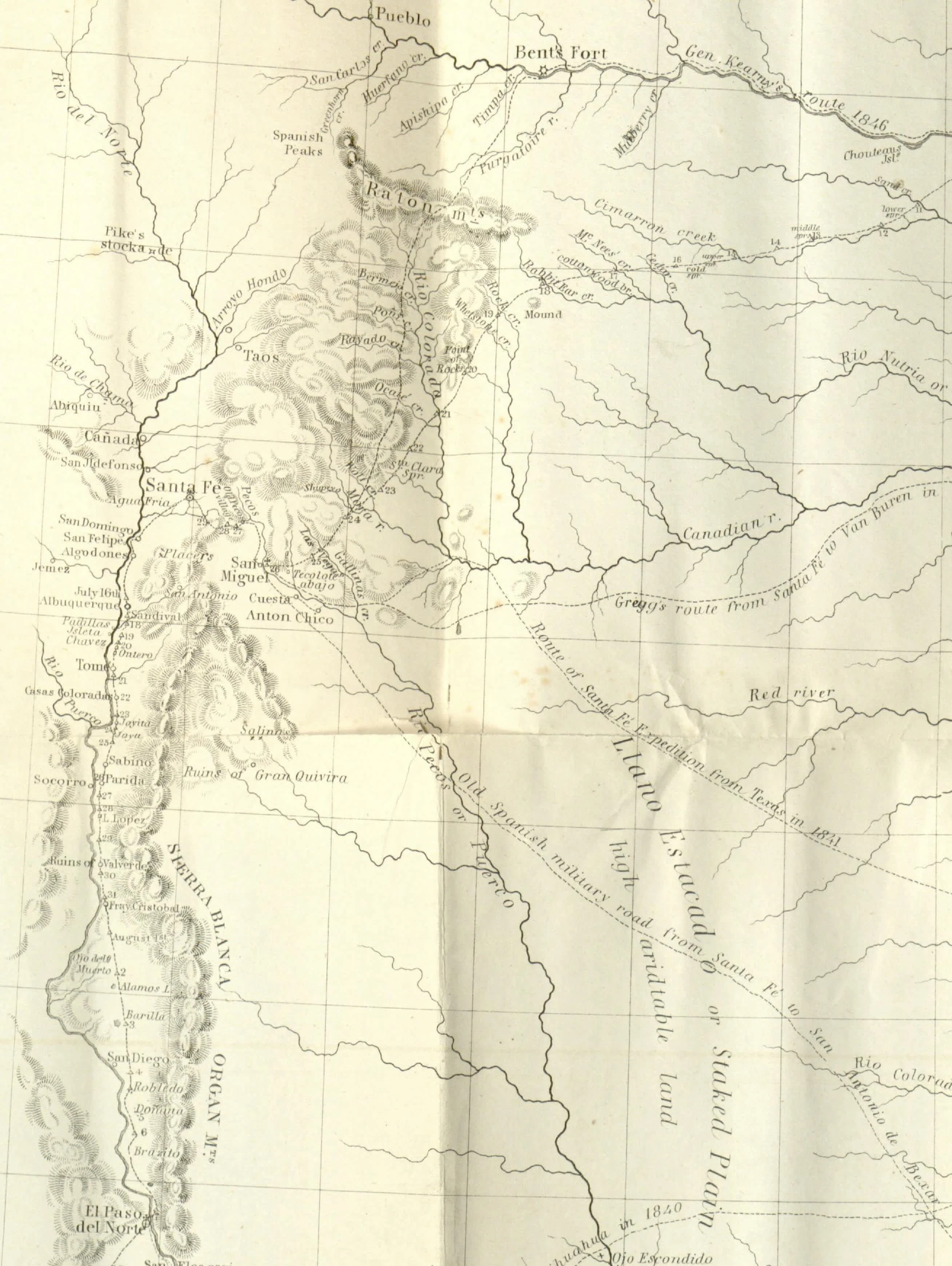

Map from "Memoir of a tour to northern Mexico: connected with Col. Doniphan's expedition in 1846 and 1847" by A. Wislizenus, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Silva family had four children at the time the war came to New Mexico in August: Teodoro (age 8), Petra (age 5), Antonia (age 2-1/2), and Vicente (age 3 months). Events that they witnessed:

1846, Aug. 9 (Sunday): As the US Army under Brig. Gen. Stephen W. Kearny approached along the Santa Fe Trail, Col. Diego Archuleta, Manuel Chaves of Albuquerque, and Miguel Pinto were commissioned by Gov. Manuel Armijo to erect defenses in Apache Canyon, the trail’s approach to Santa Fe.

Aug. 12 (Wednesday): Capt. Philip St. George Cook, after 10 days' hard ride from Fort Leavenworth, arrived in Santa Fe under a flag of truce to deliver a demand from Brig. Gen. Kearny that Gov. Armijo to surrender. The governor responded that he would oppose the invasion, and after dismissing the messenger, called his men to arms. Likely this news reached Bernalillo the next day.

Aug. 14 (Friday): Governor Armijo unexpectedly ordered his men to stand down in Apache Canyon, and after resigning, fled southward with 100 of his dragoons. (It’s rumored that James Magoffin bribed Armijo to end his resistance.) Col. Archuleta remained ready for battle, despite the order, through the weekend (even as Brig. Gen. Kearny proclaimed himself military governor of New Mexico at Las Vegas the next day).

Aug. 17 (Monday): The US Army reached the entrance to Apache Canyon. At the Pecos River crossing, however, a messenger from acting Governor Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid informed that Gov. Armijo had resigned and that he would receive the occupying force in Santa Fe the next day.

Aug. 18 (Tuesday): At 6 p.m., the US Army took possession of Santa Fe, accepting the surrender of acting Governor Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid. Again, the next day the news likely reached Bernalillo.

Aug. 23 (Sunday): The US Army began organizing its occupation of New Mexico with the construction of Fort Marcy north of the city. After rumors reached Santa Fe that Armijo would return to retake Santa Fe, Brig. Gen. Kearny marched with a force of 700 men southward to Tome (south of Albuquerque) over the coming week. This would have been the first sizable US force to pass through Bernalillo.

Sept. 22 (Tuesday): Brig. Gen. Kearny, back in Santa Fe, appointed merchant Charles Bent as the civilian governor of New Mexico, replacing Vigil y Alarid, who left Santa Fe for Aldama in Chihuahua Estado. The former governor’s cousin Donaciano Vigil became his secretary.

Sept. 27 (Sunday): Brig. Gen. Kearny, with 300 dragoons, passed through Bernalillo on his way to California. The turbulence of the times was noted by a lieutenant when he wrote of his surprise that “a lady graced the apartment” of the priest at San Felipe de Neri Church in Albuquerque openly.

Oct. 19 (Monday): After Lt. Col. Phillip St. George Cook departed from Santa Fe, he passed through Bernalillo on his way to California. He described the town as “the prettiest village in the territory. Its view, as we approached, was refreshing; green meadows, good square houses, a church, cottonwoods, vineyards, orchards – these jealously walled in, and there were a number of small fat horses grazing. The people seem of a superior class, more handsome, and cleaner. But parts of this had sand hillocks, with their peculiar arid growths.”

1846, Dec. 19 (Saturday): Once the American defenses in New Mexico were left to Col. Sterling Pierce, former officers Diego Archuleta and Tomas Ortiz began plotting a rebellion up in Taos. Their cause was only aided when those parts of the Kearny Code, the set of laws governing the military occupation of New Mexico, that granted its residents political rights “enjoyed only by citizens of the United States,” were repudiated by US President James K. Polk.

1847, Jan. 19 (Tuesday): Open rebellion broke out at Taos while Gov. Charles Bent was visiting. A mob of Tewa partisans from Taos Pueblo under Pablo Montoya (who styles himself the “Santa Anna of the North”) shot the governor full of arrows and scalped him in the middle of town. Prefect Cornelio Vigil was hacked to death, as were Sheriff Stephen Lee and circuit attorney James W. Leal, despite pleas for mercy. In Mora, rebel leader Manuel Cortes captured a party of traders from Missouri and had them all shot.

Jan. 24 (Sunday): Col. Sterling Price carried out a pincer assault on the Taos rebels, sending Israel Hendley up to Mora, while he marched up the Rio Grande valley. Although Hendley was pushed back, Price’s force overwhelmed Col. Diego Archuleta at Santa Cruz.

Jan. 29 (Friday): Col. Price defeated Taos insurgents at the Battle of Embudo Pass, destroying the last substantial defense set up by the Mexican rebels against the Americans.

Feb. 1 (Monday): The Americans returned to Mora with cannons and leveled the village, ending local resistance.

Feb. 4 (Thursday): Pablo Montoya surrendered at Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Church in Taos, ending the rebellion. He was executed soon after.

June 26 (Saturday): Insurgents appeared near Las Vegas. A week later they tried to occupy part of the town but were repelled by Maj. Edmondson.

July 9 (Friday): The last of the Taos insurgents were defeated at Cienega Creek.

1847, Sept. 15 (Tuesday): US troops occupied Mexico City. A new Mexican government replaced Santa Ana’s deposed regime at Queretaro.

1848, Feb. 2 (Wednesday): The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ends the Mexican-American War. Among the provisions welcoming residents of the annexed territories, the US government is obliged to protect land grants given to recipients by either Mexico or Spain, but only if they petitioned for title to the land given them. Although Vicente Silva and his family did not live there yet, the most pertinent grant to his life will be the Las Vegas Grant.

Building up to the 1850 Census

The central plaza of Mesilla, Mexican border town that culminated in a crisis in 1853, resolved by the Gadsden Purchase. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Although it doesn’t appear that Antonio Silva ever took part in any of the fighting or insurrections that took place in the Mexican-American War, it wasn’t until peace returned that the family continued to increase.

1848: After the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was ratified on Friday, Mar. 10, questions arose immediately on how to administer the new territories. The State of Texas sought to extend its borders to include all lands to the west of the Rio Grande, which as a result of the treaty also served as the state’s southern border. Although the initiative had some backing (Secretary of War Marcy in particular supported carving out Santa Fe County from the eastern half of what is today’s New Mexico), no one locally took it seriously.

Even after Mexico let go of its northernmost citizens for good upon ratifying the treaty on Friday, May 26, and after word of the treaty’s ratification arrived in Santa Fe on Wednesday, July 19, any extension of Texas that included the old colonial capital and towns like Bernalillo would never gain traction. Instead, New Mexico joined Oregon and California in the line to become territories and eventually states.

José Guadalupe: The next Silva child was likely conceived in March 1848 (probably around the time that the family celebrated the baptism of Vicente’s cousin, María Antonia Mora, daughter of Juan Domingo Mora and Vicente’s aunt Dolores Silva). Guadalupe was born on Dec. 21, 1848, in Bernalillo, and he was baptized five days later on Dec. 26, 1848, at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores mission church in Sandía. Padrinos were José Ynes Perea and María Ygnacia Perea of Bernalillo (probably related to Dolores). Padre J. Manuel Gallegos performed the ritual. (Page 69 of Bernalillo Baptisms Book 1846-1853, Book I.)

Although the treaty ending the war could have been an inspiration, he was more likely named for his maternal grandmother, Guadalupe Romero. At the time of his birth, Teodoro was 10 years old, Petra was 7, Antonia was 5, and Vicente was 2 years old.

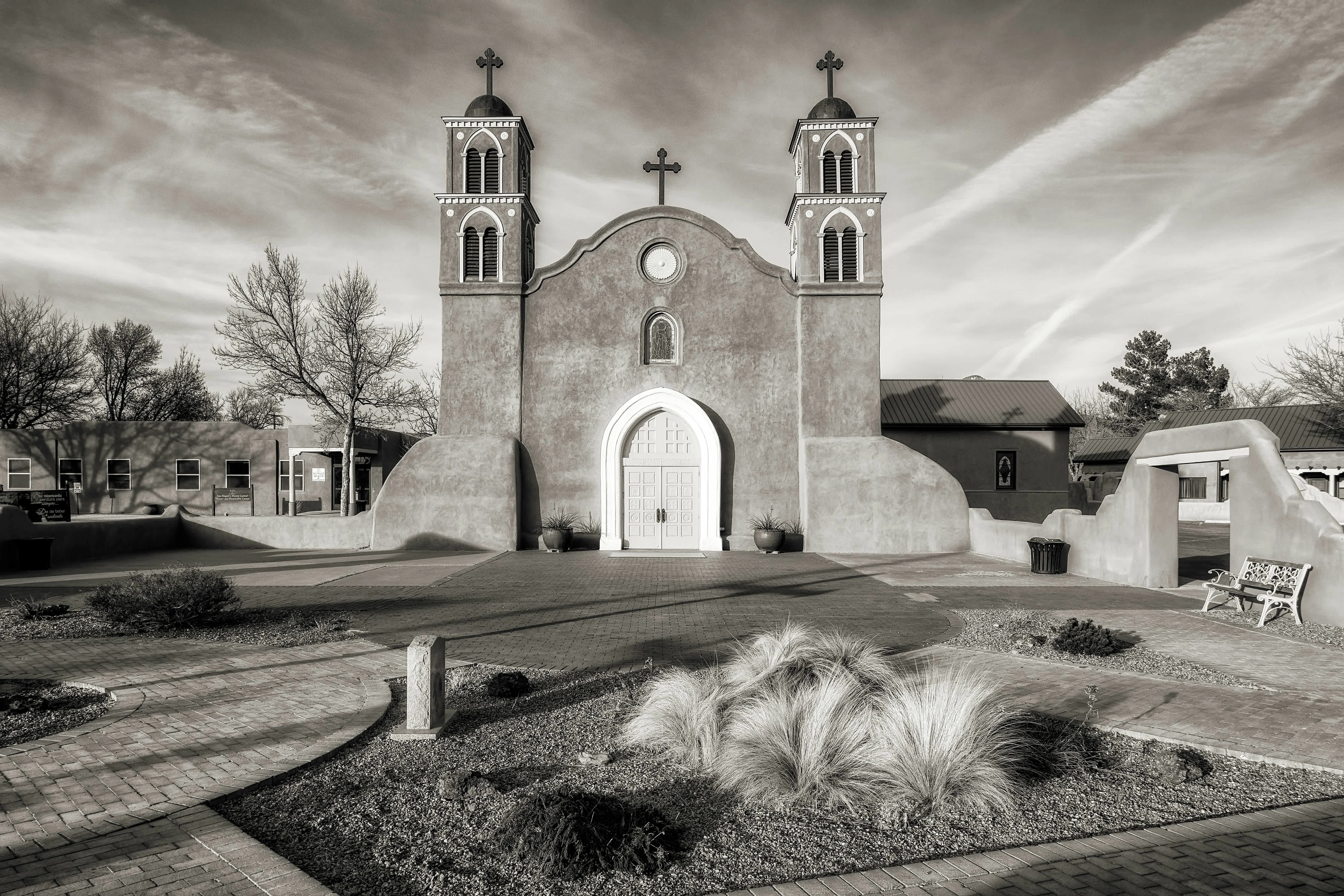

San Miguel Mission Church in Socorro, baptismal location of Vicente's wife, Telesfora Sandoval, who was born in nearby Lemitar. Photo by Claud Richmond via Unsplash.

1849: Military Lt. Col. John M. Washington struggled through October to maintain order from Santa Fe. On Sunday, Mar. 4, the marriage of Lemitar residents Juan Sandoval, 24-year-old son of Antonio Sandoval and Manuela Jaramillo, and María Josefa González, 18-year-old adoptive daughter of Juan Domingo González, at the Mission Church of San Miguel in Socorro, sets up the birth of Vicente’s wife, Telesfora Sandoval, who is born nine months later. On Wednesday, July 4, trader William Kronig set out from Independence, Missouri, for New Mexico. According to his notes, sometime between October and December, he enlisted in the militia defending Taos and met one Jesús Silva in the company of Kit Carson, Joaquin Leroux, and Robert Fisher. At the time, Vicente's uncle was 17 years of age.

1850: On Jan. 8 (Tuesday), Telesfora Sandoval was baptized the daughter of Juan Sandoval (son of Antonio Sandoval and Manuela Jaramillo) and María Josefa Gonzales (daughter of Juan Domingo Gonzales and Ana María Archuleta) at San Miguel Mission Church in Socorro (Padrinos were Miguel Gabaldon and María de la Luz Torrez, Padre José Vicente Chavez officiated). Back east, US President Zachary Taylor failed in his intrigues to create a new state out of New Mexico. Indeed, locally, such popular personalities as Judge Charles Beaubien and Padre Antonio José Martínez in Taos agitated against immediate statehood in favor of territorial status. Although tensions with Texas intensified over the summer, with populist Governor Peter Hansborough Bell raising troops to assert the state’s claim to Santa Fe, the territory’s existence was enshrined in September as part of the Compromise of 1850. Around the same time, the Catholic church carved off a part of the Diocese of Durango to create a new diocese based in Santa Fe. This brought French-born cleric Jean Baptiste Lamy to the region.

The Census of October 1850

New Mexico Bureau of Immigration image published for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The Bernalillo home of Vicente’s paternal grandparents, Juan José Silva and María Juana Gutiérrez, was enumerated by Jim Geddings, Kentucky-born Santa Fe circuit court clerk, in the 1850 Census on Oct. 15. Juan José, age 87, was a farmer whose wealth was assessed at $530 (roughly $21,500 today); wife María Juana reported her age as 60; son José Rafael (Vicente’s godfather) lived with the couple as a farmer at age 31; son Manuel remained single at age 24 (he’d marry next year); son Jesús María had reached age 18, and was described as both literate and a farmer; so too was son Juan Cristoval, age 16. Son José Francisco was also enumerated at age 24, as was his wife María Pabla Lucero, age 26, and their children: Nestora, age 6; José Felipe, age 3; and María Josefa, age 2. Granddaughter Juana María Mora, daughter of Juan José's oldest, María Dolores Silva, and her husband Domingo Mora, lived with them at age 10. Also found there was María Ruperta Silva, likely daughter of María Juliana, at age 6; and adopted child Ascencion Salazar, age 15. Also registered at the home was servant José Ramón Montoya, age 60.

The family of Vicente’s aunt Guadalupe was enumerated the day before, on Oct. 14, also by Jim Geddings. Her husband Jeronimo Montoya, age 38, was a relatively wealthy farmer worth $1700 (roughly $69,000 today); wife María Guadalupe self-reported as age 28; daughter María Rempa was 11, daughter María Josefa was age 8, and Jeronimo’s sister María Antonia Montoya was age 25.

Also enumerated on Oct 14 was Julian Perea (age 30), who lived as a servant in the home of his father-in-law Librado Martin (age 75, worth $460, or $18,650 today) and brother-in-law Juan (age 48). Julian’s wife, María Dolores 26) had by this time three children: Juliana (age 5), María Areano (age 3), and Jesús María (age 1).

On Oct. 16, German-born merchant Charles Blumner in Santa Fe enumerated the home of Julian Rael (age 50), a shepherd (whose worth was $6, or $250 today) whose family included wife Ignacia (Vicente Silva’s aunt), and their children José Emiterio (age 12), María de la Luz (age 11), Manuel (age 10), Rafaela (age 8), Antonio (age 5) and Guadalupe (age 7). Adjacent to the Rael household was farmer Demetrio Perea (age 40) and his family.

The family of Antonio Silva and Dolores Perea, and those of their other siblings, as well as the household of Ysidro Perea and Guadalupe Romero, were not enumerated.

The Silva family in the 1850s

1851: After Texas and New Mexico signed an agreement brokered by President Millard Filmore, the boundary between the state and the territory was set. Texas wouldn’t threaten New Mexico again for another ten years. In January, John S. Calhoun, a Filmore appointee, becomes the first governor of New Mexico Territory to assume office under its Organic Act. He attempts to appease the wealthy Spanish families that had run the territory behind the scenes during its Mexican period, as well as with Padre Antonio José Martínez in Taos in the hope of maintaining good relations with the already changing church. Bishop Lamy arrives in Santa Fe in August, and almost immediately faces hostility by and large among the formerly Mexican priests, who remain loyal to the Bishop of Durango.

There may have been a child named Manuela born in 1851 whose name didn't appear in the baptismal registry, but who did appear in the 1860 census.

1852: While going east to return his family to Georgia, John S. Calhoun, New Mexico's first territorial governor, died of scurvy near Independence, Missouri. Secretary John Greiner acted as governor until William Carr Lane is appointed by President Filmore. An enmity with military commander Col. Edwin Sumners created chaos in Santa Fe. (This was probably the period in which life for Vicente, then 6 years old, was at its most ideal – spending time with his father helping in the family fields. Little happened in Bernalillo during this period.)

1853: The Mesilla crisis erupts along the new US-Mexican border when Gov. Lane orders the town seized. Chihuahua Gov. Ángel Trias sends troops in response. Lane is soon replaced by incoming President Franklin Pierce with the less controversial David Merriweather, and James Gadsden is sent to Mexico to negotiate the purchase of the borderlands that included Mesilla.

Baptismal record for Jesus Maria Silva, Vicente's younger brother and associate of Billy the Kid at Fort Sumner. Pages 2-3 of Bernalillo Baptism Book 1853-1865, Book II.

Jesús María: Born Oct. 13, 1853, in Bernalillo, and baptized three days later on Oct. 16 at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores mission church in Sandía. Padrinos were Juan Montoya and Petra Perea. Padre Ramón Salazar performed the ritual. (Teodoro was 15 years old, Petra was 12, Antonia was 10, Vicente was 7, and Guadalupe was 5 years old.)

1854: Former Mexican governor Manuel Armijo, who had returned to his estate near Lemitar, died on Jan. 20, and was buried at the Sagrada Familia Church in that town (where Vicente’s future wife, Telesfora Sandoval, had just turned four.) Bishop Lamy precipitated a crisis when he ordered priests to exclude sacraments from those households that couldn't pay tithes and ordered fees for baptisms to be tripled. Padre Antonio José Martínez stood up against this order. Back east, William Pelham was appointed the territory’s first Surveyor General. His first big task was to verify those grants that sought protection from being redistributed under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

1855: James A. Lucas proposed to create from Mesilla a new territory across the south of New Mexico that he called Pimeria. The town became the seat for anti-Hispanic sentiment among the early newcomers to the territory throughout the 1850s.

1856: As Vicente Silva turned 10, Bishop Lamy took advantage of Padre Martínez becoming ill to replace the old priest's preferred assistant Ramón Medina (Mexican) with Damaso Taladrid (European). This turned into a crisis over the summer, with Bishop Lamy excommunicating Padre Martínez and Medina in September. Many parishioners continued to attend mass with Padre Martínez, who held services at his home.

On July 22, Vicente’s grandfather, Juan José Silva, passed away in Albuquerque at age 84. A few months later, on Nov. 21, Penitente leader Bernardo Abeyta likewise passed away up at Chimayo, where he founded one of New Mexico's most revered pilgrimage sites. Bishop Lamy attempted to buy the Santuario for the diocese, but Abeyta’s widow, María Manuela Trujillo, refused to sell it, choosing to keep the church in the family instead.

1857: At the end of the previous years, six deacons of Montferrand arrived in New Mexico at the behest of Bishop Lamy. Among these was Joseph Fialon (age 23), who immediately went to Bernalillo to oversee the construction of a new Our Lady of Sorrows Church in that town (funded in large part by the Perea family of Vicente’s mother’s cousin, José Leandro Perea). By April, Padre Fialon was performing baptisms there. (About the same time, Joseph Fayet went to Anton Chico, and over the next few years Joseph Marie Coudert went to Las Vegas, Jean Baptiste Ralliere went to Tome, Jean Auguste Truchard went to Socorro, and Gabriel Ussel went to Taos.) In the same year, Alexander Grzelachowski, Las Vegas’ “Padre Polaco,” left the parish he helped found to take over the parish of Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Manzano. (He had come to New Mexico as a military chaplain during the war, and was appointed the role of parish priest by Bishop Lamy when he arrived in New Mexico.) Jean François Pinard (also a former military chaplain) replaced him as the parish’s second priest.

The only known photo of Padre Antonio José

Martínez, revered Mexican priest of Taos who inspired many native New Mexicans to stand up against injustices perceived as being carried out against them by resisting the fiscal reforms decreed by the newly-installed French-born Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy in the 1850s. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

1858: Again, in March, Padre Martínez and Padre Mariano Lucero of Arroyo Hondo were excommunicated by Bishop Lamy over their refusal to collect levies for the archdiocese. Padre Machebeuf was sent to Taos to replace Martínez. The “Americanos” (including Kit Carson) vowed to protect Lamy’s replacement when violence was threatened. In August, Rev. Etienne Avel was poisoned while taking the Eucharist in what was likely a botched attempt to assassinate Padre Munnicum in Mora. This killing aptly demonstrated the heightened tensions among "Mexicano" and non-native Catholics in New Mexico.

Aug. 23, 1858: Antonio Silva and Dolores Perea organized a double wedding for their two daughters, Petra (age 17) and Antonia (age 15) at the old Nuestra Señora de Dolores Church in Sandía. Petra became the wife of José Valdez of El Guache (near Bernalillo), while Antonia became the wife of Charles Monroe. By this time, Teodoro was age 20, Vicente was 12, Guadalupe was 10, and Jesús was 5. (In the same year, Juan José Herrera, the future “Mexican Joe,” married Eliza, the daughter of French priest Jean François Pinard. They remained in a ‘tolerable state of happiness’ living in the household of the parish priest, where he served as a majordomo for Our Lady of Sorrows Church until the start of the Civil War.)

1859: Petra became the first to give Antonio Silva and Dolores Perea grandchildren, with the birth of José Leandro Valdés (baptized July 26 in Bernalillo). Father Joseph Machebeuf finally left Taos and went north to establish a new Diocese of “Pike’s Peak,” to provide church services amid the ongoing gold rush there. Eventually, he will become the first Bishop of Denver.

The 1860 Census: Calm Before the Storm

View of Sandía Peak from Corrales before sunset. Photo by John Fowler via Wikimedia Commons.

While the news of political turmoil captures the attention of Americanos in New Mexico Territory, the US census for 1860 is organized. Henry Winslow is assigned to the town of Bernalillo, and he finds there on July 13 in Precinct 1 (the town of Bernalillo) the family of Antonio Silva (age 50 a farmer with $100 in real estate and $300 in personal estate). Living with him is his wife, Dolores Perea (age 40), daughter Petra Valdés (age 19) and her son José Leandro (age 1), daughter Antonia Monroe (age 18), son Vicente (age 15), son Guadalupe (age 13), daughter Manuela (age 9), and son Jesús María (age 7).

Winslow also enumerated on the same day the nearby home of the widow María Juana Gutiérrez (who self-reported her age as an impossible 40 years old, with $600 in real estate and $700 in personal property). Living with her were Vicente’s godfather José Rafael Silva (age 26), his younger brother Juan (Cristobal, age 21), and young servants Leonor (age 12) and María Ruperta (age 15).

A day later on July 14, Winslow enumerated the home of María Manuela Martínez, age 52, a widowed farmer worth $2,000 in real estate and $1,200 in personal property. Living with her was Julian Perea, likely a widower of Manuela’s daughter Dolores, age 34. His oldest son, Julian, was reported as age 15, Mariano Perea was 14, and Jesús Perea was 11. Also living with them were Petra Martínez, age 21, and Madine Montolla, age 19 (the latter probably related through Julian’s sister).

On Tuesday, July 17, Winslow enumerated Corrales and found there the home of Jesús Silva (age 31, farmer with $80 in real estate and $150 in personal estate), along with his wife María Feliz Gutiérrez (age 26), daughter María de la Luz Silva (age 5), son Francisco Antonio Silva (age 3), and youngest son José Felipe Silva, age 11 months. Servant Antonia Griego (age 12) also lives with the family.

About a week after the States back east elected Abraham Lincoln (territories did not vote in the presidential election), Dolores Perea gave birth to her and Antonio Silva’s surprise last child:

José Gregorio: Last born son of Antonio Silva and Dolores Perea, born in Bernalillo shortly before being baptized Nov. 17, 1860, at Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Bernalillo (mother was 44 years old). His godmother was Dolores Chaves. Padre Joseph Fialon (age 26) performed the ritual. (Teodoro was 22 years old, Petra was 19, Antonia was 17, Vicente was 14, Guadalupe was 11, and Jesús was 7 years old.)

The Civil War: A Bernalillo Timeline

January 1861: Although Americano journals watched the events back east carefully, it was unlikely that a lot of attention was given to the rising Civil War in Bernalillo. The Santa Fe Gazette, the newspaper of record for the time, concentrated more attention on yet another attempt to create a constitutional convention, one that would allow the territory to ask for admission to the Union as a state, even while the southern states were exiting the Union.

February 1861: Although most of the Silva family remained around Bernalillo, in late January, Vicente’s uncle Manuel Silva and aunt Juana had baptized a daughter up in Anton Chico. Less than a week later in early February, the Confederate States of America declared themselves a country before Lincoln could take the oath of office.

March and April 1861: After Lincoln became president and the war started, Texans again began to view New Mexico as their territory. Despite Washington's preemptive decision to separate the northern half of New Mexico and create Colorado Territory, many Mexicano citizen groups made public declarations of support for the Union, while many non-Mexicano residents who supported the Confederacy left. In the middle of it all, Governor Abraham Rencher, a native of North Carolina, soon lost his position to Henry Connelly, despite being pro-Union. The polarization between the states became complete after Lincoln’s forceful response to South Carolina taking Fort Sumter in April.

May 1861: US military authorities ordered 3,400 soldiers to leave their posts and rally at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. This left New Mexico exposed to raids by hostile Navajo, and attacks by the Confederates, who began to mass troops at Mesilla.

August 1861: Lt. Col. John Baylor, after capturing Mesilla in the last week of July, declared the organization of a new Arizona Territory, all New Mexico lands south of the 34th parallel (about 5 miles south of Socorro) as a member of the Confederacy.

September 1861: Three divisions of volunteers were planned at Santa Fe in response to the Confederate threat. Among the militia officers was Vicente’s mother’s cousin Jose Leandro Perea, who would serve as Maj. Gen. of the third division, along with brigadier generals R. H. Evan and Estanislao Montoya.

October 1861: Paddy Graydon was sent to Lemitar to recruit a column of spies that would infiltrate into Confederate territory in the service of the Union. Lt. Col. John Baylor soon reported: “The Mexican population are decidedly Northern in sentiment and will avail themselves of the first opportunity to rob us or join the enemy.” Vicente’s Uncle Jesús Silva was commissioned a captain, and he recruited 79 men from Galisteo and San Pedro (mostly failed prospectors). These men spent the war mostly fighting Navajo raiders. Further north, Lt. Juan José Herrera was commissioned at Las Vegas to help form a new regiment of mounted infantry.

December 1861: Vicente’s second cousin Francisco Perea (son of Juan Perea, Vicente’s mother Dolores’ cousin, and nephew of Leandro Perea) recruited and organized his own battalion of militia. While the opening battles of the Civil War distracted the new Lincoln government, a European army led by the French landed at Veracruz. This marked the start of Napoleon III’s attempt to take over Mexico.

January 1862: New Mexico Territory pledged to “drive off the audacious invader” in response to the creation of Arizona Territory. The spies of Lemitar began to infiltrate Mesilla with men disguised as poor apple farmers. Their instructions were “talk only in Spanish, listen only in English.”

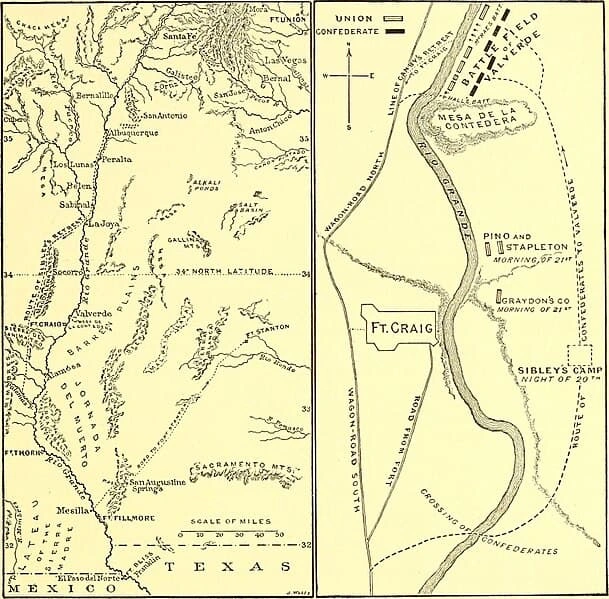

From Battles and Leaders in the Civil War, a part of The Century War series. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Feb. 21, 1862 (Friday): Col. John Baylor led the Confederate Texan army at the Battle of Valverde, defeating General E. R. S. Canby. Socorro is occupied the next day.

Mar. 2, 1862 (Sunday): Many residents fled Albuquerque as the Texans approached, and after they seized the town, Texan troops turned the abandoned homes into quarters. (Bernalillo likely prepared to evacuate those who wished to flee as well.) Confederate Gen. Henry Sibley caught up with his army there as they prepared to march northward toward Colorado. The Territorial government in Santa Fe prepared to evacuate to Las Vegas.

Mar 5, 1862 (Ash Wednesday): Gov. Henry Connelly officially moved the Territorial government into the Exchange Hotel off the Plaza in Las Vegas. Soldiers of nearby Fort Union prepared to meet the Texans in battle. (During Confederate occupation, the Silva children were the following ages: Teodoro, age 23; Petra, age 20; Antonia, age 18; Vicente, just turned 16; Guadalupe, age 13; Jesús, age 8. If Manuela and Gregorio were still alive, they’d have been 11 years and 17 months, respectively.)

Mar. 10, 1862 (Monday): The first eleven Texan troops (mostly former Santa Fe residents who returned from Mesilla wearing Confederate uniforms) entered Santa Fe. By the end of the week, Texan forces fully occupied the capital (its stores were distributed to households across the city before the invaders arrived to deny their capture).

Mar. 23, 1862 (Sunday): Gen. Henry Sibley, from his headquarters in Albuquerque, proclaimed an amnesty for all pro-Union militia who would lay down their arms in the next ten days. Not many took him up on his offer.

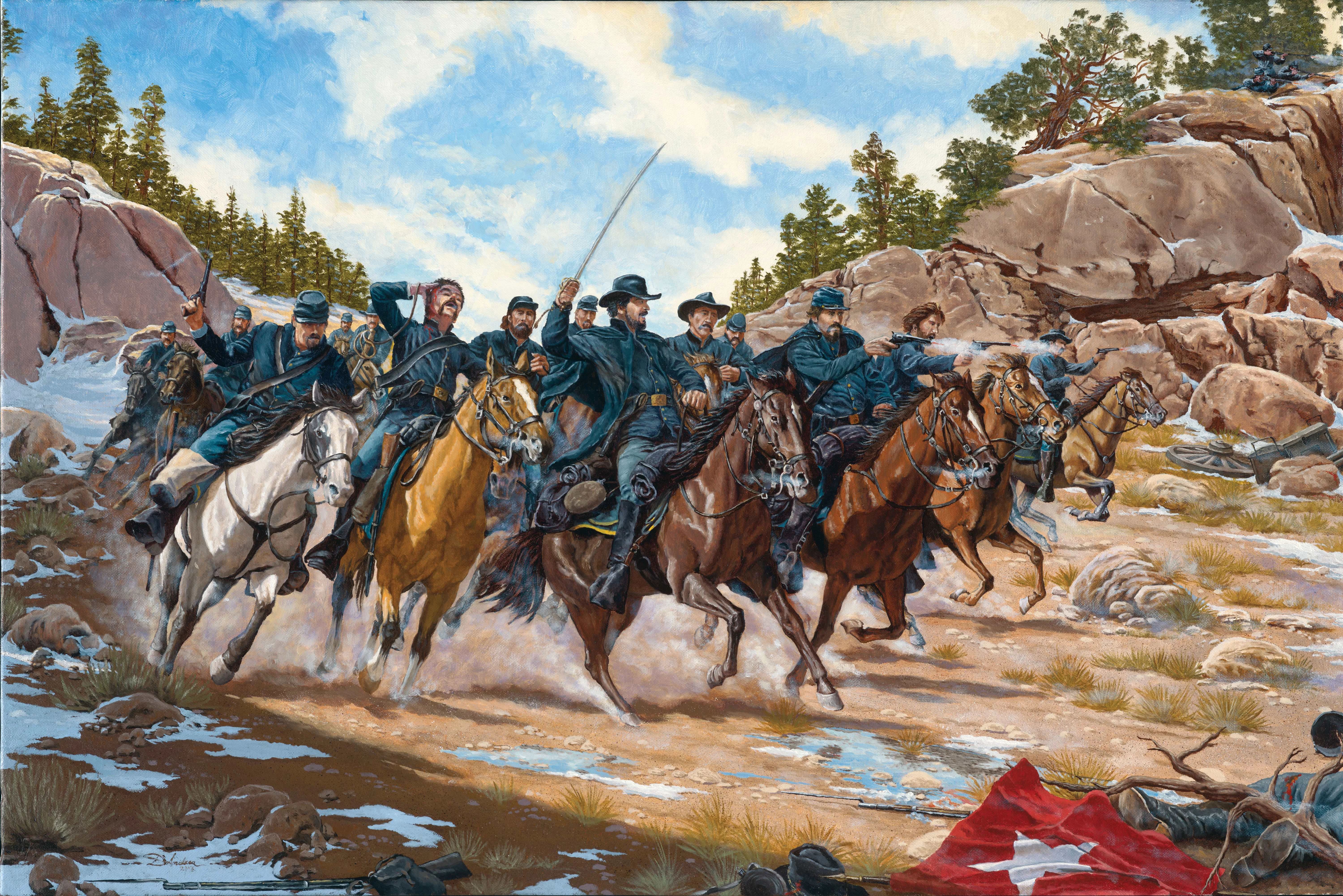

Mar. 26, 1862 (Wednesday): After the Texans advanced eastward into Apache Canyon on their way to Las Vegas, Col. John Slough and Maj. John Chivington intercepted them at Bernal. The Texans fell back to Johnson’s Ranch.

"Action at Apache Canyon," depicting Maj. John M. Chivington's attack on the supply train of Gen. Henry Sibley's Texan invaders (the figure on the beige horse riding on Chivington's right may well be Padro Polaco). Painting by Domenick d'Andrea (2015) via Wikimedia Commons.

Mar. 28, 1862 (Friday): While Col. Slough held off the invaders at Glorieta Pass, Maj. Chivington, guided by Alexander Grzelachowski (Las Vegas’ former Padre Polaco) led a small group of 20 soldiers to destroy the Confederate supply train while it waited at Johnson’s Ranch. The raiding party returned without losing a man. Lacking supplies, the Texans immediately withdrew to Santa Fe.

Apr. 7, 1862 (Monday): The Texans, under Confederate Col. William Scurry, left Santa Fe behind and began their long march back to Mesilla after more than a week of plundering what they could.

Apr. 11, 1862 (Friday): The first Union scouts arrived in Santa Fe just as the Union Army arrived at Galisteo. Col. Canby advanced above the town of Albuquerque, setting up camp at La Tijera. Col. Gabriel Paul led the Union Army back into Santa Fe over the weekend and then rode south with a force to harry the retreating Texans. (Likely, Bernalillo was liberated by Col. Paul’s men before the end of the weekend.)

Apr. 25, 1862 (Friday): Union troops retook Socorro.

July 4, 1862 (Friday): After the arrival of the California Column in Mesilla, the Confederates were finally driven from New Mexico Territory.

Summer 1862: South of the border, as the French under Napoleon III continued their campaign to take Mexico, a superior invading army was defeated by Ignacio Zaragoza at Pueblo. The defeat was miraculous enough that Cinco de Mayo has been celebrated ever since by Mexicans both in Mexico and the United States. Nevertheless, the war continued in Mexico in tandem with the battles of the American Civil War (and, indeed, Pueblo fell to the French again, a month later).

Late 1862: The US Army began its campaign against the Navajo and other hostile indigenous people by establishing Fort Sumner in the Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River. Francisco Perea, Vicente’s second cousin, was elected to serve as New Mexico’s Delegate to Congress in November’s elections. Shortly after Dr. John Whitlock was likewise elected to represent San Miguel County in the legislature, he traveled to Fort Stanton and got into a personal fight with Paddy Gradyon of the Lemitar spies. Both men died as a result of their gunfight.

1863: Francisco Perea was installed as New Mexico’s Delegate to Congress. He remained in the nation’s capital for the remainder of the war. Back in New Mexico, Mangas Coloradas was killed by the US Army after the chief of the Chiricahua Apache sought negotiations under a flag of truce. Future war chiefs Geronimo and Victorio took this up as a casus belli. The French seized Mexico City on June 7, and Napoleon III arranged the creation of a new Mexican Empire under Austrian Prince Maximilian on Oct. 3. At the end of the year, the Navajo attempted to seize Fort Sumner near Bosque Redondo. The attack was witnessed, among others, by Padre Joseph Fialon, formerly of Bernalillo, but now chaplain of the new post.

1864: In response to the Navajo attempt to attack Fort Sumner, Kit Carson led a company of New Mexico volunteers to Canyon de Chelly, where some 8,000 were captured and made to endure a 300-mile death march later called The Long Walk. Only 3,000 Navajo survived the trek to Bosque Redondo. The Union side of the war pledged an alliance with the Republic of Mexico, stating it would not recognize any monarchy in Mexico City. Nevertheless, on May 29, Maximilian and his wife Charlotte of Belgium landed at Veracruz. Back in New Mexico, secondary sources claimed that Telesfora Sandoval married John Andrew Bernes (or Birney) in Socorro on July 11 as her first husband.

Early 1865: On Jan. 20, Vicente’s uncle Cristobal married María Merced Gallegos at Bernalillo. Julian Perea and María Pabla Silva served as witnesses, and the ceremony was officiated by Tomas de Aquino Hayes. Although Francisco Perea wasn’t reelected as New Mexico’s Delegate to Congress in November (his cousin José Francisco Chaves, a veteran of the Battle of Valverde, was elected instead), he remained in Washington as a power broker through what would have been President Lincoln’s second term. Indeed, he was present in Ford’s Theater on the night that Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on Apr. 14, just five days after Confederate General Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

After the War: A New Invasion

The original Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Bernalillo was abandoned in 1971 in favor of a new Our Lady of Sorrows Church that was built adjacent to it. The old church was restored after 1977 as the Santuario de San Lorenzo. Photo by John Phelan via Wikimedia Commons.

Late 1865: After the war came to an end, Americano farmers and ranchers began to file claims on lands not protected by grants, displacing long-settled families in places like Bernalillo. It’s possible that Vicente Silva’s family was among these early land grab victims – having Perea relatives in Washington might not have provided any real security to the Silvas. In November, the peace that the US Army imposed on the Mescalero Apache came to an end as they left the Bosque Redondo Reservation for their traditional lands. The Navajo would do the same three years later. The civil war in the Catholic Church intensified as well. Using the US-Mexican Republic alliance against the French Imperial government in Mexico, Padre Martínez asked the Territorial legislature to label Bishop Lamy a foreign prelate who was hostile to the long-native Mexicano clergy.

1866: Rather than face a battle-hardened American enemy, French troops withdrew from Mexico, leaving Emperor Maximilian to defend himself. The Mexican Republicans quickly took the initiative in northern Mexico. This year, Texas cowboys Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving brought some 2,000 free-range cattle to Fort Sumner, blazing a trail that would become a regular route for cattle drives within the Pecos River valley. In July, President Andrew Johnson replaced Dr. Henry Connelly as governor with Robert Byington Mitchell, an appointee often described as inept. In October, Eliza Pinard (daughter of former Las Vegas parish priest François Pinard) filed for divorce from Juan José Herrera over abusive behavior that likely resulted from PTSD following his service as a New Mexico volunteer officer in the Civil War. On Dec. 1, the term Santa Fe Ring appeared for the first time in the weekly newspaper of that city.

1867: Eliza Pinard’s suit for divorce was dismissed in March. Within six days, Juan José Herrera filed a countersuit, claiming that she carried herself in “an open state of adultery like a prostitute.” Effectively, he destroyed her reputation in Las Vegas, and both she and her father were driven from the city. On June 19, after being captured near Queretaro, Emperor Maximilian was executed, putting an end to Napoleon III’s project to create a Mexican Empire. On July 27, Padre Martínez died, putting an end to organized resistance against Bishop Lamy’s changes to ecclesiastical New Mexico. In August, the Jesuits returned to New Mexico and were at first given the church at Bernalillo as their residence. Around the same time, Juan José Herrera concluded his countersuit for divorce, and having denied Eliza Pinard access to his property, he and his brother Pablo decided to leave New Mexico and seek their fortunes along the Transcontinental Railroad route in what will become Wyoming Territory.

1868: In March, the Jesuits left Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Bernalillo after they were given San Felipe de Neri Church in Albuquerque as their residence instead. They left their first home in New Mexico with a newfound reputation for good winemaking (the industry remains in its infancy though – in a couple of years, New Mexico would produce 16,000 gallons over the year. Another 14 years after that, this number would grow to over a million gallons). In early April, the Herrera brothers appeared for the first time near Cheyenne. Juan José Herrera began to use the nickname “Mexican Joe.” Kit Carson passed away from an aneurysm in Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory, on May 23.

1869: The suppression of the Comanche improved the security of the staked plains beyond Las Vegas. Hispanic families began to move into Lincoln and San Miguel counties in large numbers. On May 10, the first Transcontinental Railroad connected the Atlantic coast with the Pacific coast of the United States. In Santa Fe, Bishop Lamy orders the construction of a new cathedral. Its walls will be built around the old parochial church that served Santa Fe, even while the church continued to be used. Telegraph wires now connected Fort Leavenworth with Santa Fe. Gabriel Sandoval was baptized the younger brother of Telesfora Sandoval in Socorro on Nov. 18.

1870: Gov. William Pile ordered the burning of Spanish records to heat the Palace of the Governors, erasing a lot of early colonial history. By March, the Kansas Pacific railroad between Leavenworth and Denver reached the Colorado territorial line. By April, Mexican Joe Herrera went into grocery selling at South Pass – unfortunately, the boomtown community was shrinking rapidly in size even before he got there.

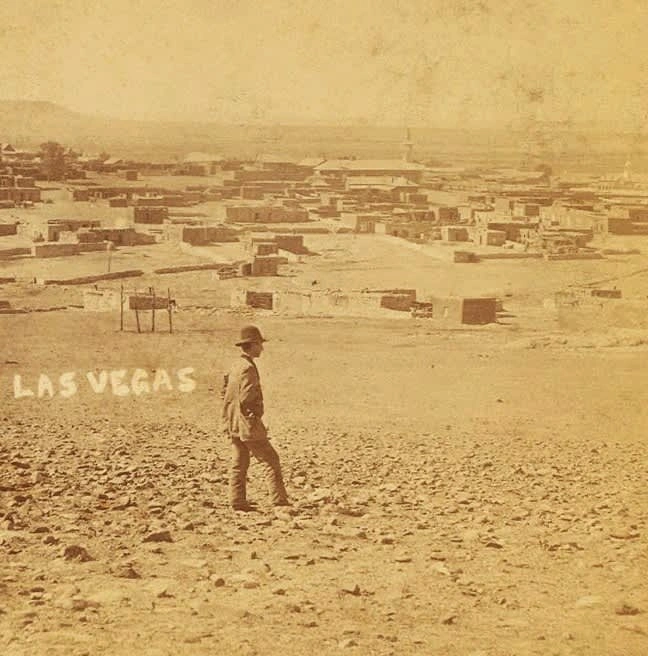

The 1870 Census: Vicente recorded in Las Vegas

Photo taken in the late 1800s by F. E. Evans, image via Wikimedia Commons.

On June 1, George Haws enumerated the Herrera brothers at South Pass City. He found them on South Pass Avenue opposite the post office and listed all of them as freighters. Joseph Herrera (age 32) was described as having $1,500 in real estate, and $6,000 in personal property (inventory). Pablo, age 26, and Nicanor, age 23, were also joined by an even younger brother named Catarino (age 14), who was described as a teamster. Among the other Mexicanos in town was Epifanio Baca, who worked as a freighter. He eventually married Rosario Lucero, the woman who eventually became Vicente Silva’s mistress and provided him with his only son to survive to adulthood. (Soon after, the Herrera brothers gave up on their grocery business and moved to Brown’s Hole on the Green River in Colorado, where they took up ranching… and rustling. Likely, Vicente Silva and others from New Mexico eventually joined their operation.)

The Herrera brothers were also listed in the same census as living with their mother, Paula (age 48), a widow with property at Ojitos Frios in the Tecolote Valley. Her home was valued at $1,030, and she had a personal estate of $800. (Such double enumerations were not unheard of at the time.)

Rosario Lucero (age 17), meanwhile, was serving as a housekeeper for Isidro Troncoso (age 58) in Lower Las Vegas, according to Demetrio Pérez, who enumerated them on June 30. On July 7, Pérez found the household of Antonio Silva (age 60, farm laborer), who lived with his wife María Dolores (washerwoman), son Vicente (age 24, farm laborer), son Jesús (age 17, farm laborer), and Petra Gutiérrez (age 11, adopted). Living nearby was Guadalupe (age 22) and his wife Isabel (age 24), María Antonia (age 25) living alone from her husband, Charles Monroe, and Petra (age 26), living alone from her husband José Valdez. This indicated that the Silvas moved to Las Vegas before the summer of 1870.

Of course, not all of the Silvas migrated to Las Vegas. Rafael, Vicente’s godfather (age 51), remained at Bernalillo on a farm valued at $400, with $2,000 in personal property, a daughter named Ana María (age 7), another daughter Beatrice (age 5), adopted genizaro son Lorenzo (age 7), son Juan José (age 8), and his (and Antonio's) mother María Juana Gutiérrez (age 80). Nearby was the home of Juan Cristoval Silva (age 37, farm laborer) whose home was worth $300, and who had $1,000 in personal property, wife María Merced Gallegos (age 17), son José August (age 3), and infant Ascensio (age 6 months). Rafael would soon move to Lompoc, California, where he’d register to vote by Aug. 19, 1875.

Vicente's uncle Jesús Silva (age 40) remained at Corrales in a house worth $400 (he also had personal property worth $100). He lived with his second wife Feliz (age 27), daughter María Luz (age 15), daughter Francisca (age 13), son José Felipe (age 11), daughter Josefa (age 4), and son Ignacio (age 1).

In Anton Chico, Demetrio Pérez found the family of Julian Rael on Aug. 5. Rael (age 64), who had a home worth $300 and personal property worth $1,554, was the husband of Ygnacia Silva (age 52), Vicente’s aunt who had served as his godmother. Nearby was the household of another of Vicente’s uncles, Manuel Silva (age 43, farm laborer) who had a home worth $300, and had personal property worth $200, as well as a daughter Ruperta (age 13), and son Manuel (age 11), Vicente's cousins.

Further south, J. McShaw enumerated the town of Lemitar, and found there the household of Juan Sandoval (age 40, tailor), along with his wife Josefa (self-reported as age 27). The children who still lived with them included son Martin (age 13), daughter Marquese (age 10), daughter Predicanda (age 16), daughter Pablita (age 9), daughter Tomasita (age 7), and son Gabriel (age 1). Missing from the list was eldest daughter Telesfora, who again was probably married and living with a first husband somewhere else.

1870s: The Cowboy Years

Group of New Mexico cowboys photographed by John F. Jarvis in 1890. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

1871: On Jan. 10, José Chavez y Chavez, Vicente’s future associate, first appeared as the bridegroom of Leonora Lucero at Carrizozo. He self-reported that he was the son of Juan José Chavez and Ysidora (Teodora) Chavez, while his wife was the daughter of Juan Lucero and Marcellina Jaramillo. In May, newspaper publisher Ashbury Conway edited his last edition of the South Pass News before quitting and joining the Herrera brothers down in Brown’s Hole. The J. S. Hoy manuscript suggested that Conway remained in a constant state of inebriation and “in keeping with the local custom, had a habit of acquiring other people’s cattle.” In Lemitar, meanwhile, Telesfora’s maternal grandfather, Juan Domingo Dolores de la Cruz Gonzales, died at age 83. (The widower of Ana María Archuleta, he was baptized on May 6, 1787 in Albuquerque the son of Felipe Gonzales and María de la Luz Gurule.)

1872: On Feb. 13, José Chavez y Chavez celebrated the baptism of the first of his two sons José Anastasio Chavez in Tularosa (the second, Adecasio, would come 18 months later). In Santa Fe, six years after the idea was first mentioned in a newspaper, the legal machinations of Attorney General Thomas B. Catron against butcher August Kirchner resulted in the rise of the real Santa Fe Ring – then a clique consisting of attorney Stephen Elkins, Chief Justice Joseph Palen, attorney William Breeden, and Catron. Epifanio Baca, meanwhile, returned from Brown’s Hole and wedded Rosario Lucero at Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Las Vegas on June 17, the start of her ill-fated marriage. Further east, by September, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad had extended tracks to Dodge City. Criminals almost immediately took over the railhead and turned it into a rough-and-tumble hurrah town. In November, Pablo Herrera married his first wife, Maggie Bentley, at Laramie in Wyoming Territory.

1873: On Jan. 24 (Friday), Jesús María Silva (age 19) married Cesarea Mares, daughter of Santos Mares and Macedonia Chavez at Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Las Vegas. Witnesses were Nepomuceno and Veneranda Lucero. Padre Boudier officiated. (Cenobio, the couple’s first child came nine months later.) As the new couple settled into married life, Jesus’ sister Antonia undertook to sell off her house and furnishings, apparently after Charles Monroe abandoned her. Back in Bernalillo, José Leandro Perea, Dolores Perea’s cousin, has increased his wealth substantially, and by this time, in addition to a profitable flour mill, he was said to own 125,000 head of sheep. Meanwhile, the fight over ownership of the Las Vegas Grant began. By the end of the year, the Santa Fe railroad reached Las Animas in Colorado.

1874: On April 4, the Las Vegas post office announced that it was holding two letters for Vicente Silba (age 28), and one for Col. Jesús Silva, his uncle. Among the other letters held was one for José de la Cruz Pino, a future constable. Lorenzo López was serving as San Miguel County Probate Judge. Back in Bernalillo, on June 10, Leandro Perea finished the consolidation of his landed interests there, buying out his nephew Francisco Perea, who subsequently moved to Albuquerque. On Oct. 10, The Las Vegas Gazette reports on the completion of a new stone edifice on Moreno Street for Judge López – this will later be misnamed the Vicente Silva House. In November, Joseph Glidden patented his barbed-wire fence design and set about to market his product across the West. On Dec. 5, a letter waited at the Las Vegas post office for Antonio Silva, Vicente's father.

1875: On Feb. 12, the Diocese of Santa Fe was promoted to that of an Archdiocese. On Apr. 24, the Las Vegas Gazette reported that Judge Lorenzo López had finished installing a tin roof on his building of native brownish stone on Moreno Street (he stepped down from Probate Judge this year). In June, Governor Marsh Giddings died while in office. He was succeeded by Samuel Beach Axtell, up to that point Governor of Utah Territory. On Aug. 31, a letter came for Teodosio Silva (indicating he still had his faculties to this point). On Sept. 21, Maggie Bentley filed for divorce against Pablo Herrera up in Cheyenne for abandonment. In December, the Santa Fe railroad reached La Junta in Colorado Territory.

1876: On June 16, Antonia Silba filed for divorce from Charles Monroe, again for abandonment. Shortly after America celebrated its Centennial, Colorado was granted statehood, while New Mexico remained only a territory. On Oct. 24, Zenovio Silva was born the son of Jesús Silva and Cesaria Marez. In November, Jack Tunstall arrived in Lincoln County and soon came into conflict with local Irish merchants Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan.

Early 1877: On July 6, the Las Vegas post office announced letters waiting for Vicente Silva (age 31) and Dona Matilda (Telesfora) Silva (age 27), indicating they may have gotten married by this time. Before marrying, Vicente and a dozen other New Mexico vaqueros were to have ridden to Wyoming as ranch hands, most likely in support of Juan José Herrera in Brown’s Park, Colorado. Around this time, Cheyenne was described as a particularly dangerous hurrah town on the Transcontinental Railroad. On June 8, a major fire broke out near Las Vegas’ town plaza (a precursor to an even bigger fire that would hit a few years later). On Aug. 25, the case of Antonia Silva vs. Charles Monroe was referred to a special master to take testimony over whether divorce might be granted over Antonia's accusations of being abandoned.

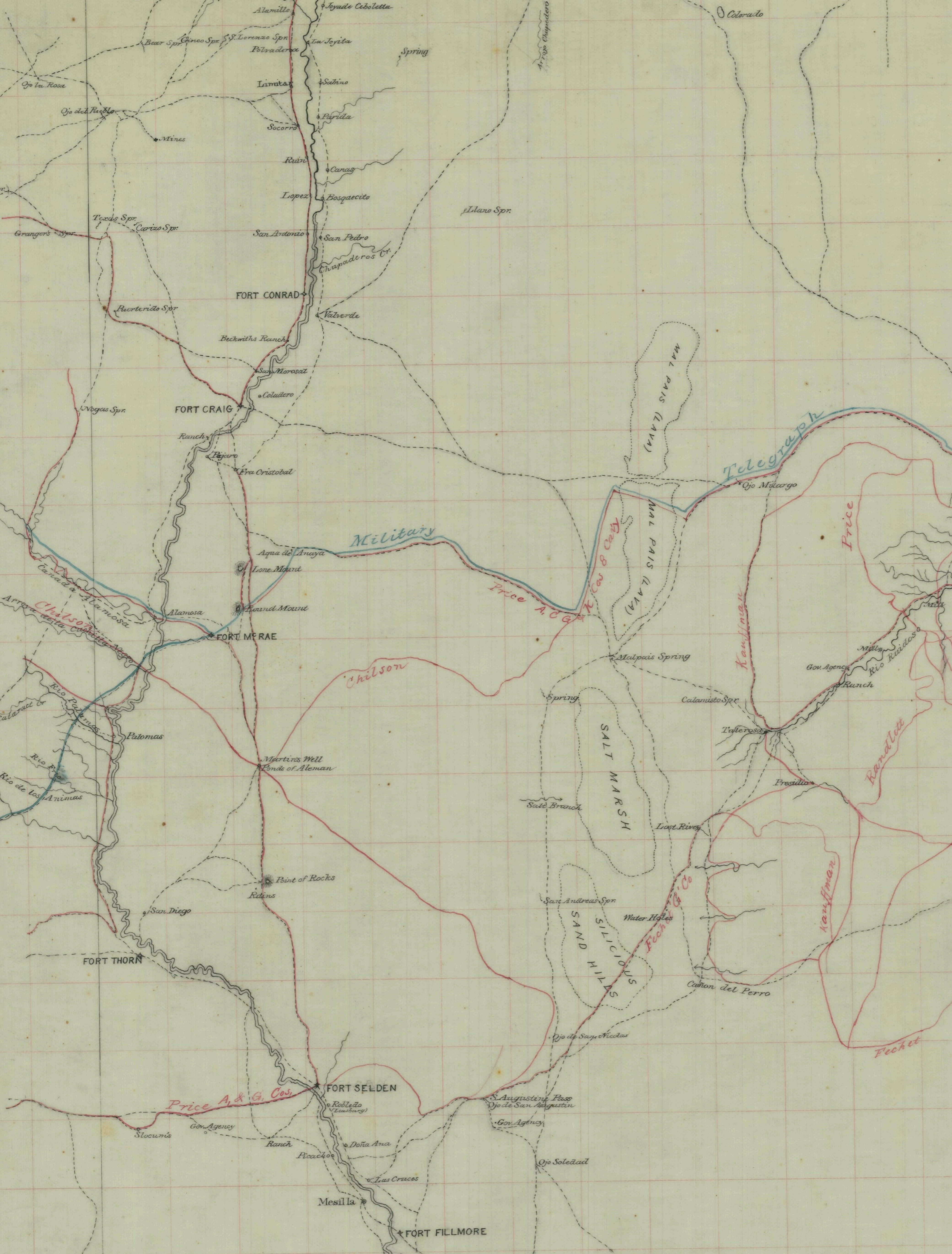

An 1873 military map of communication routes between Lemitar (north) and Mesilla (south) in the Rio Abajo area of the territory. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Late 1877: On Oct. 31, letters were left at the Las Vegas post office for Carpio Mares, Lorenzo Rael, and Vicente Silva. On Nov. 10, an item in the Mesilla Valley Independent indicates that one Vicente Silva was accused of receiving smuggled items and of smuggling, and was acquitted at Mesilla. This may be the same Vicente Silva if he in fact was in the area of Socorro for a time (the village of San Pedro where he and Telesfora married might be the ghost town not far to the south of Socorro rather than the mining community close to Bernalillo where Vicente later had a ranch). On Dec. 7: Dolores Chaves, wife of José Leandro Perea, passed away at 51 years of age. She was buried in Bernalillo at the parochial church her husband funded.

Early 1878: On Feb. 18: Jack Tunstall was shot to death, triggering the Lincoln County War. José Chavez y Chavez, former justice of the peace and constable, emerged as one of the Regulators who, along with Billy the Kid, went after Tunstall’s murderers, including Sheriff William Brady. On Apr. 1, Sheriff Brady was killed in an ambush. On May 4, Special Investigator Frank Angel arrived in Santa Fe to examine the records of Governor Samuel Axtell’s government. On May 15, Jesús María Silva and Juan Felipe Maraquin were killed by a pair of Texan outlaws at El Tule east of Fort Sumner. This Jesús was likely Vicente’s uncle.

Summer 1878: On June 4, the widowed José Leandro Perea married a distant cousin, Guadalupe Perea, as his second wife. Jesús Perea and Manuela Baca witnessed, and J. P. Faure conducted the ceremony. The Las Vegas Gazette reported on July 10 that carpenter Orlando Smith completed his windmill on the town plaza. Intended to provide drinking water for the ox teams that stopped on their way between Santa Fe and Missouri, it only worked properly for a couple of months before it fell into disrepair. José Santos Esquivel appointed the first police force around the same time in response to a rise in drunken disturbances, and it included Juan Leiva, Feliz Mares, Canuto Maes, and Pablo Domingues. On Sept. 4, at the recommendation of Frank Angel, President Hayes suspended Gov. Axtell and appointed in his place Gen. Lew Wallace of Indiana.

Late 1878: Judge Mariano Sabino Otero, who married a Perea second cousin of Vicente Silva, was running as the Republican candidate for Delegate to Congress. In September, one Juan Perea was killed in Puerto de Luna by an assassin in the night. Florencio Sandoval was detained as a suspect but was later released for lack of evidence. (He was later killed by the Herrera brothers, possibly as part of a vendetta that resulted from this killing.) In October, Federal troops were sent into Lincoln County to put an end to the war there. At the end of November, the first tracks of the Santa Fe Railroad were laid along Uncle Dick Wooton’s old toll road. Within a week, the first locomotive symbolically crossed into New Mexico Territory as tracks continued to extend southward toward Raton.

1879: By January, outlaws began to populate Las Vegas as the railroad got closer to the town. The townsfolk chose to build a station about a mile and a half from the town plaza. By March, Doc Holiday, suffering from tuberculosis, arrived in Las Vegas, as evidenced by his being fined for keeping a gaming table on Mar. 8. However, he returned to Kansas to wait for warmer weather after the winter cold got to him. By April, a new tent city was started once the amount of people and businesses coming to town exceeded the number of available buildings. On June 5, Manuel Barela and Giovanni Dugi, having killed a man the previous day, were taken to the windmill in the town plaza and lynched. Afterward, the structure was called the Hanging Windmill. By June, up in Colorado, Mexican Joe Herrera selected a cause that eventually got him run out of Brown’s Park - taking up arms in support of the Utes against the incoming wave of miners and prospectors. On July 1, AT&SF tracks are laid into the new train station for Las Vegas, New Mexico. Everything was set for the first train to arrive on July 4…

Like this project

Posted Nov 24, 2024

A biographical study of New Mexico historical figure Vicente Silva, from the time his parents married to the arrival of trains in Las Vegas, New Mexico in 1879.

Likes

1

Views

120