5 Exceptional Black Prima Ballerinas That Will Inspire You

Black American prima ballerinas who changed ballet dance culture forever – A timeline

The percentage of Black dancers in American ballet has been abysmal since ballet grew its wings so long ago. For Black American prima ballerinas, this number feels more like an anomaly than a probability. The stakes are so much higher, too, and the chance of becoming a prima ballerina is unfortunately of least concern for a Black ballerina that takes on the ballet world and its racial implications that are ascribed to it. But there are dancers, both gifted in dance and passionate about change, who took it on and created incredible shifts in the dance world in the process.

Other than Misty Copeland, here are ballerinas who changed the culture of ballet for the better.

Aesha Ash, the sacrificial lamb and exceptional ability

Late 90s early 2000s

In many ways, Aesha Ash was a sacrificial lamb. With immense natural ability, she was forced to make many heavy sacrifices due to her race, gender, and the time period in which she began, where inclusivity was not the priority and many “firsts” had already been accomplished. [The “there can only be one” rhetoric in predominantly white spaces, to be clear]. Her dancing, however little provided, we can see is both fluid and artistically poetic, dancing from a place only she knows. Aesha Ash is an innately powerful dancer and has become a beautiful influence on the black ballerinas that came after.

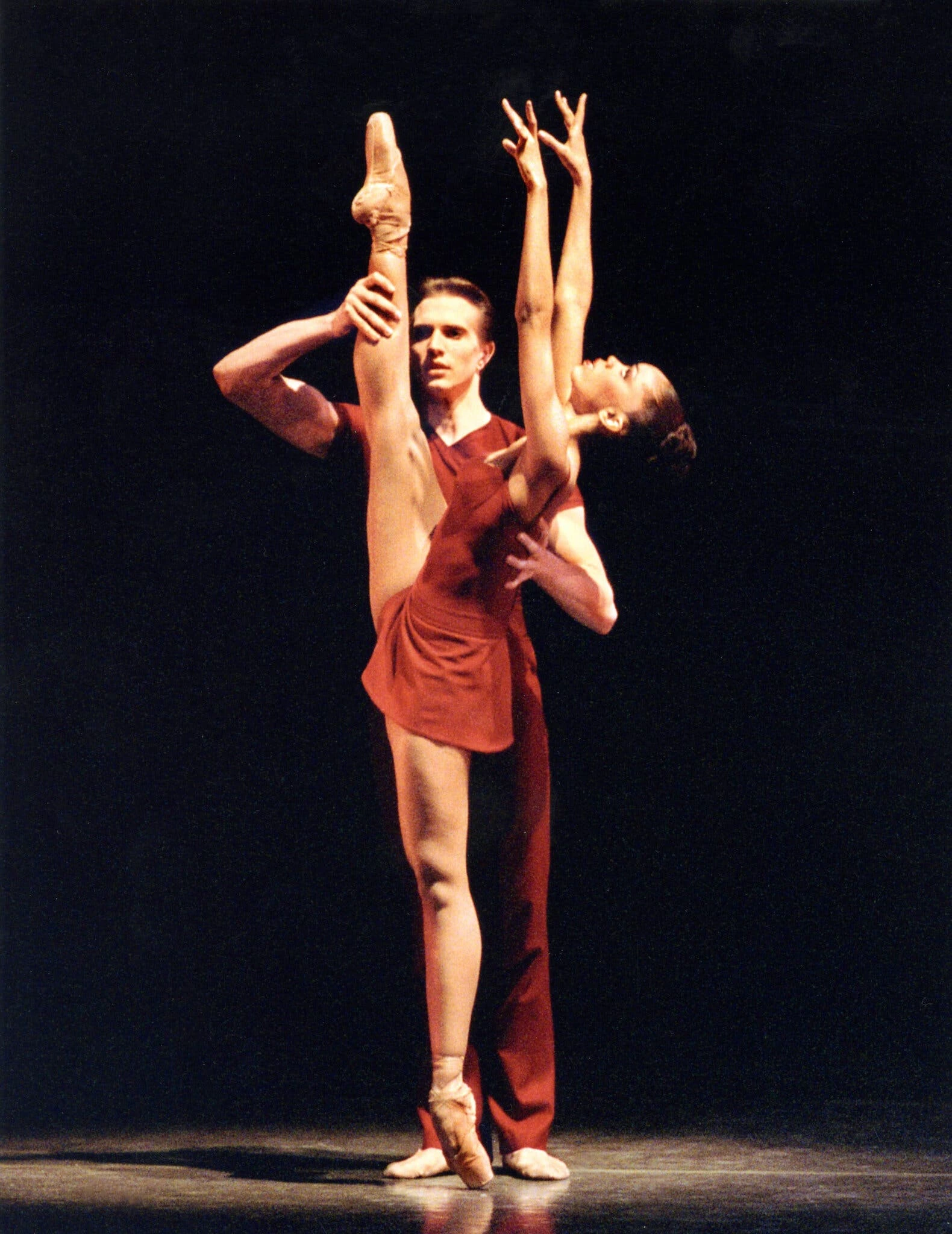

Aesha Ash, New York Ballet (2002)

She was the only Black dancer at New York City Ballet during her time there. Although not the first, she had to learn how to deal with her presence as “the other” regardless. Because of this, it was bigger than just dancing for her. “It was so much bigger than that,” Ash said. “I was trying to battle stereotypes and biases on that stage every single night. And I succeeded in some and I failed in others.” She eventually became a soloist at acclaimed Béjart Ballet in Lausanne, Switzerland. After deep feelings of isolation, however, she began dancing with LINES Ballet in San Francisco.

I truly believe even in the midst of her starting “late” as a ballerina, she had the potential to become a principal. Although when one’s heart isn’t in it, when they’re just “going with the motions,” sometimes passion is better channeled into other arenas.

Teaching and community outreach became the cause that fulfilled her initial mission as a dancer: to combat negative stereotypes against little Black girls, that they can only be “aggressive” or “angry” or “masculine,” and nothing else. Black girls that were in similar neighborhoods as Ash and didn’t know how to become a dancer, let alone a ballet dancer.

This deep drive to combat negative stereotypes led her to extend her ballet knowledge and life lessons back to her hometown in Rochester, New York, where she challenged the racial stereotypes in major Black cities with her organization called The Swan Dreams Project. She intertwined the use of Black culture and life with the imagery of the Black ballerina, showcasing grace, joy, and beauty that ballet can give. This showcased that grace and talent in ballet can, in fact, be achieved in predominantly Black communities. Ash did this while exposing youth to the imagery and experience of dance directly, in her own neighborhoods, and teaching spontaneously in her own communities.

Progressing to other cities like Oakland, the Swan Dreams Project also awards scholarships and gives a dance home to the inner city ballerinas with no other place to go.

Swan Dreams Project, Photography by Thaler Photography

Aesha Ash, Black American prima ballerina

Most recently, she became the first African American woman to be a permanent professor at the School of American Ballet, and has now risen to an associate head position in the ballet department.

Due to the severe lack of Black female teachers at higher, acclaimed ballet schools like this, her travel experience, her perspective and empathy illustrated, coupled with her extensive dance experience makes her an even greater asset. Often, we neglect the importance of simply being in the presence of an presumed anomaly, with the faith and hope that us ourselves could be something greater. And these nuances she brought to ballet over the years will now be taught on a pre-professional level to rising ballerinas. This is huge.

Her greatest desire: to inspire kids and the rest of the world to see beyond their stereotypes of Black people, specifically Black women, and that we can be multi-faceted, graceful, angelic, soft.

She was a first in many things, but was a trailblazer long before that, adding to the fabric of dance history for the prima ballerina, a figure that is not just a soloist or principal in a company, but a figure that exudes grace on a grand level, and brings ballet to the world in artistically beautiful and intelligent ways, with a rare quality that many simply cannot capture or recreate. The next few dancers capture this essence, of elevating ballet beyond titles and accolades.

Michaela DePrince, orphan during war times to world-class prima ballerina

Early 2010s to 2020s

Beating all odds and becoming one of the most inspiring ballerinas to date, Michaela DePrince started off as an orphan during war times in Sierra Leone. She jettisoned to becoming a soloist at Dutch Ballet, and eventually a soloist at Boston Ballet. Before any of that though when she was still a child, she was labeled as “cursed” and sold to an orphanage with little to no food.

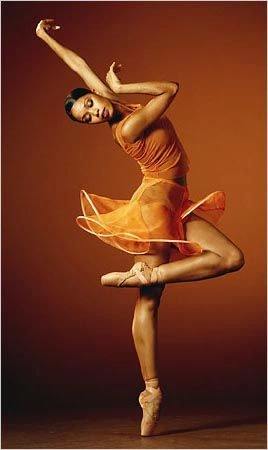

Her experiences of dealing with constant violence, lack of food, and no inkling of what dance even was, her life as a ballerina didn’t start off as traditional. It wasn’t until she was adopted by an American family at four years old that her dreams of becoming a ballerina would rise and soar. DePrince has an immaculate quality of dancing and artistry, and she has the potential to be one of the leading dancers and ballerinas of the 20s and beyond.

Michaela DePrince

She is currently Soloist at Boston Ballet, and has done multiple guest performances at other notable companies as a principal. She was also one of the youngest dancers to appear with the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Her divine ability to manifest her greater fate of doing something she truly love feels almost pre-ordained: from seeing a small magazine clipping of a ballerina, to clinging onto it everyday, to deciding right then that she would be a ballerina, with it being the only dream that kept her out of the realities of her situation. Then it happened, a dancer that seems that they were literally born for this thing, but also to do more than just dance.

From “breaking the curse” to conquering the just as unlikely odds of becoming a ballerina, this is a beautiful transformation of faith, dedication, and opportunity. Now a prolific dancer with exceptional natural, technical, and artistic ability, she is a beautiful addition to the linage of Black American prima ballerinas.

She continues to use her platform for more philanthropy like her work at War Child Holland as an ambassador, and Dare to Dream, an event that brings beauty and light to children in the same situation as she once was, providing resources, fun, and new perspectives.

Virginia Johnson, one of the original Black American prima ballerinas

Late 1960s to late 1990s

Virginia Johnson, alongside Arthur Mitchell, was one of the founding members of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, an all-Black ballet company that shifted the ballet paradigm tremendously. She soon rose to principal dancer at the Dance Theatre of Harlem, with a career spanning over thirty years, and one of the most diverse and extensive repertoires any Black woman had ever had up until that point. She is currently the Artistic Director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

The Dance Theatre of Harlem, and her presence there, brought a new eye, access, and artistic direction to ballet. Her presence continues to be a reigning inspiration for many Black ballerinas that have come after her, and has been cited constantly by modern ballerinas as their inspiration.

In one of the most notable ballets at the Dance Theatre of Harlem, she performed as the principal in Creole Giselle, a re-imagination of European ballet, Giselle. This was a major feat for black ballerinas, solidifying the presence of Dance Theatre of Harlem as well as the intensity and beauty of the Black ballerinas and their collective stories. Taking place in the bayou of Louisiana and not the pebble streets of a medieval village, the historical significance of this piece on the dance world hasn’t been replicated since.

Solidifying her legacy, Johnson founded the Pointe magazine, an internationally-acclaimed online and previously in-print dance magazine with over millions of readers annually.

Llanchie Stevenson, the trail-blazing ballerina

Mid 1960s to mid 1970s

One of the first principal dancers at the Dance Theatre of Harlem, she influenced the use of brown tights by wearing them over pink ones to match the color of her skin during performances. This effectively started a trend that would need to be reinvigorated for generations to come. However, Stevenson and her persuasion of doing it as a collective at the Dance Theatre of Harlem proved influential. Eventually, dance clothing manufacturers started making dance tights in various brown colors, which had never been done prior. She also danced alongside Virginia Johnson.

Llanchie Stevenson at Dance Theatre of Harlem

In addition to her influence with tights, she was also hand-selected by Alvin Ailey to join his company, who persuaded her to continue her journey as a ballerina. This was a great honor. She soon joined The School of American Ballet where she was classically trained under the “father of American Ballet”: George Balanchine. [Although she never received a contract for the company because she would “break the corps lines,” which really meant color line.]

Spearheading the revolution of brown tights may seem minute in this climate, but in a white-dominated dance world, these resources were not developed nor prioritized for the Black ballerina. Lines are extremely important for ballerinas, and flesh-toned tights define muscle as well as allow the lines to become more present. Without that option, pink tights served as a major setback for the aesthetic of the black ballerina. Once brown tights became more of the norm, this gave dancers the courage to wear brown and tan pointe shoes as well, giving ballet and its beauty fresh aesthetic perspectives, something the ballet world still does to this day.

Debra Austin, the first Black principal at a major traditional American company

Early 1970s to Early 1990s

Debra Austin at New York City Ballet

Hand-picked by George Balanchine at age sixteen to join the New York City Ballet in the corps, her story as a dancer is both extraordinary and inspiring. She began dancing at the age of eight, and at twelve, was awarded a scholarship at the prestigious School of American Ballet, the school under New York City Ballet. Her placement at both the school and the company was as unlikely as it was exciting.

She went on to become the first Black principal dancer at a major American ballet company in 1982: Pennsylvania Ballet. [this was eight years before Lauren Anderson did at Houston Ballet, commonly incorrectly cited as the first Black principal at a major American company.]

With a huge repertoire as well and a long-standing career, she did what was once unthinkable during her time. Her dancing spoke for itself.

Honorable Mention: Alicia Graf

Ultimately, the original Black American prima ballerinas paved the way, made sacrifices, and advocated and changed the culture of ballet so dancers after them could thrive, and have the luxury of focusing on purely ballet, which is really what it should all be about. The joy of it; the joy of dance.

Sources

Like this project

Posted Jun 16, 2023

Five exceptional Black American prima ballerinas that changed dance culture forever that will inspire you, including Michaela DePrince & more

Likes

0

Views

17