ARTIST INTERVIEW: Angela Bulloch

Totemic geometric structures. Eldritch sounds. Shifting moods. Stepping into this exhibition at Berlin’s Esther Schipper Gallery initially feels like skipping a dimension or two and arriving in 2001: A Space Odyssey. But whereas Kubrick’s black monolith challenges the viewer’s scrutiny, Bulloch’s twisting, colorful stacks invite the mind to play.

I gravitate towards a far corner, beside five stacked modules, centered before a wall of LED lights flickering on and off. How natural, how easy it is, for the eye to see in the place of algorithmic automations and calculated angles, the towering figure of a feminine deity, lit by a sky of stars.

Animal Mineral Vegetable is Angela Bulloch’s 13th exhibition with Esther Schipper, and features Bulloch’s newest iteration of her signature ‘Stack’ sculptures and ‘Night Sky’ installations, with the addition of a wall painting and digital animation.

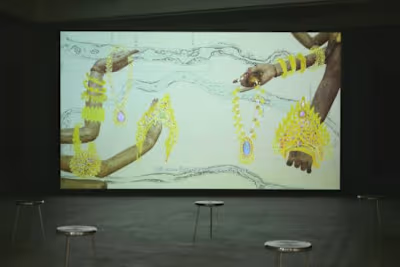

The sculptures, Pentagon Totems — composed of ‘modules’: dodecahedrons in block color, mostly stacked but sometimes singular — mark points on the exhibition floor that wind a path between, choreographed to a 15-minute light and sound display, including a six minute video projected onto the back wall.

‘I started with the model of the space’, Angela says via video-call, ‘I’m interested in measuring the world with myself —comparing space to the body. The room is an industrial type of space, not a domestic one, and it’s also really quite large,so I’ve done certain architectural interventions.’

The room Angela calls me from seems to be a chintzy London hotel, a world away from the spatial aesthetic here in Berlin, where Bulloch has lived since 1999.

‘For example, I have inserted freestanding night-sky pillars, and hidden a doorway and two pillars in this space inside much bigger ones. In the show, there are both acts of erasure and architectural gestures.’

Perhaps the show’s most obvious architectural gesture is the huge geometric wall painting, which spans across one wall and a corner. Tightly overlapping shapes — as if made by a spirograph ruler — stretch on either side like the nucleus of the big bang or as if the shapes splay out at increasing, or decreasing, speeds. Space and time bend in Bulloch’s virtual reality, and on the video projected onto the parallel wall, the universe grinds to a halt, at warp speed.

‘I wanted to make a very dramatic architectural scale wall painting, so that when it would appear in the video, you would get a reference of the size of it and the position of it, so that it locates you in the room’.

The video feels familiar; COVID-19 popularized the use of uncanny virtual exhibition software. This too is a digital mimesis of the ‘real experience’, only, with the addition of a rotating polyhedron with a face on it, a mottled cat and one other unexpectedly charming character.

‘The melancholy cauliflower is made from a cast of a cauliflower and a pipe, and it’s actually a reference within my own oeuvre. I made the original ones in the 80s when I was still a student, then in 2017, I made a revisited edition. So this reference to earlier work is like a step back in time’.

Watching the video for the first time, I latched onto this floating cauliflower like an irreverent talisman: an assurance that lurking at the heart of this mathematical and calculated exhibition, was a kind of approachable playfulness.

‘I’m working a lot with sound, light, geometric or abstract shapes, the universe, different images of somewhere very far away, and these topics, those different elements of my language, are kind of alienating, cool and detached. I wanted to add a human element or something that was, you know, a bit quirkier, that people can identify with within the film. I kind of like to think of it as a friend of mine.’

I have already noted a precision to Angela’s speech; a restrained use of adjectives; a sparse use of metaphor. Angela describes herself as ‘visually organized’, but there is a linguistic neatness too. Talking about this old friend, something softens.

‘The reason why it’s called “melancholy flower” is because its color is melon yellow and it’s a cauliflower — a linguistic slippage.’

The cauliflower is also exceptional in the exhibition for its organic, nebulous shape. I ask Angela to explain her attraction towards geometric shapes.

‘I’ve chosen a five-sided form in all of the pieces in all of the standing sculptures, except for one and that one’s called ‘Twisted Sister’. There’s a series of rhombus modules and I rearranged the order of them, and in that ‘Twisted Sister’ one, I turned one or two of them upside down. But you’d need to know the other works, to be able to realize that. So, it’s kind of like a piece of twisted language that you could only notice if you remember how they look, as there’s only one of them in the show.’

I run my mind’s eye over the edges of each stack, counting, trying to recall ‘Twisted Sister’ and crack the geometric puzzle Angela has set. Walking about a room with totems and stars, I had expected to be told to suspend intellect and analysis, but the more I talk to Angela the more I feel like the show is an exercise in critical thinking, both for the artist, and the viewer.

‘I’ve mainly worked with rhombus shapes, and I wanted to fill the gap differently. There was a part of my brain that wanted to see a different shape. You know, it was really like a fulfillment, a wish.’

She continues, ‘also, you know, the sculptures there, some of them are made with regular pentagon shapes, and some are much more irregular. And the way it looks as you walk around changes because of the way they’re put together — those sculptures look very different from different angles. So the sculptures are really a kind of provocation to walk around and look at them.’

The light display that Angela has designed enhances this phenomena, as shadows scatter over one face to another.

‘It’s a feast for the mind because their appearance changes, so you’re constantly doing adjustments with your eyes. Your eyes are trying to find the similarities, the differences, the irregularities. It’s like scratching an itchy place in the mind.’

Angela’s comment about the ‘itchy place in the mind’ jogs my memory of what the exhibition reminds me of. ‘Sensory rooms’, often filled with sound-scapes and calming coloured light displays, are often used to help those with learning difficulties or sensory impairments engage with stimuli and regulate their sensory processing. Animal vegetable mineral is also a kind of therapeutic space; a provocation to slow down and to concentrate — a valuable practice, when technology is eroding our attention-spans.

This concept of sensory play is not only the product of the show, but a fundamental component of the process of making it. In the video, besides the floating polyhedron and cauliflower, is a small, sparkling dark object. Angela speaks animatedly about the process behind creating it:

‘In the summer, I was invited to a glassworks. I put a very hot piece of glass flat on the metal table and then made a kind of dent in it with the end of a metal thing, and I put a small piece of a peanut onto that very hot glass and then put another big blob of hot molten glass on top.’

Strange, is this a traditional method?

‘No, it was a very experimental thing to do. I tried it with popcorn, potato, peanuts, different things’

The result?

‘The oil in the peanut burns, blackening the glass with a strange, rainbow, gray anthracite texture, that’s shot through with rainbow-like newton’s rings.’

I imagine Angela like a scientist in a laboratory, hyper focused and exacting. Watching the video, with its uncanny animation style, I had no idea the objects were born from real life, or from such a traditional art practice like glass-blowing.

Reading about Angela before the interview, I came across one image that surprised me. During 2010’s Art Basel, Esther Schipper suspended one Night Sky above the altar of a cathedral, the Basel Münster. It’s odd to see a panel of white, electric lights in such a traditional and sacred space, but then, isn’t the Romanesque and Gothic architecture, the stained glass, achieving what the installation does; the human approximation of the divine, the heavenly?

‘I also chose to make one in the rotunda ceiling of the Frank Lloyd Wright building in the Guggenheim. I was invited for an exhibition and I chose to do it in that “church”. It was a many-sided form, and I also I added some frameworks and some kind of architecture to the Ceiling Rotunda so that it was more justified and made parallels to the Parthenon.’

Situated in temples, these installations gesture towards a heightened consciousness. The Night Sky series are an example of technology simulating a reality beyond our reach — a view of the constellations we could literally never see from earth. As corporations like Facebook thrive off toxicity and polarization, it is easy to forget that the creation of the world wide web was in part catalyzed by LSD trips into the ‘expanded consciousness’. These control-panels of constellations seem to me like a reminder of what ‘virtual reality’ can be at its best, what it was hoped to be in the 1960s: not something invasive and homogenizing, but expansive and elevating.

What’s next for Angela Bulloch?

‘Well, there’s this show with Esther Schipper, and one in London with the Simon Lee Gallery and a third show which will be in the museum in Nantes in France. These three shows have a selection of sculptures, wall paintings and a film, so they are all linked by their method of making. But they are also quite different: the museum space is a grand, large atrium which will host the biggest night sky that I’ve made so far. That one will be opening in May, and I will be creating another film about navigating through that exhibition. So really, these are a trilogy of exhibitions’

I thank Angela for her time, and before I go, pass round the exhibition space a final time. Christina, from Esther Schipper, joins me. ‘Which one is your favorite’, she asks. Looking at the stacks, with their unique irregularities and color combinations, I find myself searching for personalities to project. As Angela mentioned, when you have a room full of standing sculptures, people very easily anthropomorphize them.

I think about what Angela said, right at the beginning of our interview, ‘there’s a kind of edge where something is related to a human or something is not related to the human, and there’s somewhere in between those two different poles, there’s a kind of line. And I’m very interested in either side of that line.’

The room is full of edges and lines, with divergent answers hinged on either side. Am I dealing with something mystic and celestial, or analytic and mathematical? Should I be responding emotionally, or analytically to the room? And are they even edges at all? Or are they angular curves of a woman’s figure? Light falls on different answers at different times.

Animal Vegetable Mineral plays with this line, this glitch between perception and recognition, where meaning gestates and slippages form. It asks the entrant to look, and to look again and twist the room in your mind’s eye like a Rubik’s cube but without solution.

* Images courtesy Angela Bulloch and Esther Schipper. Portrait of Angela Bulloch by Andrea Rossetti. Melancholyflower by Eberle & Eisfeld.

Like this project

Posted Aug 17, 2023

Artist interview for Ran Dian with Angela Bulloch. Bulloch is a Turner prize nominee and member of the Young British Artists, alongside Tracey Emin.

Likes

0

Views

16

Tags