The Subconscious Splinters of Isaac Pelayo

Interview Article with artist Isaac Pelayo. I developed the questions and conducted the interview with Pelayo. From our conversation I created a full-length article and analysis based upon our discussion.

Read the article below or follow the link to read the article in Tainted Magazine.

Los Angeles painter Isaac Pelayo is rethinking the foundations and philosophies of art making and, in doing so, taps into the human condition.

25 minute read

The Subconscious Splinters of Isaac Pelayo 5

For Isaac Pelayo, art is in his DNA. He has spent nearly his entire lifetime with a pencil in hand or behind the canvas. Enthralled by the art he saw in museums, inspired by the street art he encountered growing up in Los Angeles, and encouraged by his family, he rapidly gained his technical abilities, leaving him unrivaled even at an early age. With a few decades under his belt, he refuses to slow down. From commissioned paintings to album covers, his work is in high demand, but that is not what motivates him. Despite cultivating an exponentially growing following, Pelayo defies complacency, challenging himself and the art world’s definition of what it means to be an artist and the responsibilities that entails.

Simultaneously meticulous and intricate alongside visceral and raw, Pelayo disrupts how we view works of art. He leaves us second-guessing the nature of our reality as his uncanny photo-realistic depictions melt into beautifully abstract brushstrokes stamped with his signature vocabulary of iconography. While saturated with his own emotions, many of which cannot help but hit close to home with many of us today, his work calls into question the world around us: issues within art history, socioeconomic class structures, and even our own sense of self and well-being are illuminated. Through the honesty and authenticity he brings to his practice, he strives to rekindle sensations, memories, and sentiments that lie dormant within us all.

Layering Latent Liminalities

From highly rendered portraits of celebrities adorned with a third eye to expressive recreations of Renaissance Madonnas with yellow smiley faces, Pelayo undermines the expectations set forth by years of art history by synthesizing unconventional elements. Figuration and abstraction, sophistication versus the colloquial, meticulous technique colliding with gestural mark-making—his work thrives in the reconciliation of opposites we never thought possible. He is fusing the fragments of art, society, and life back together. The spaces in between are not solely where his style develops, but we come to learn that this is where his identity as an artist is forged.

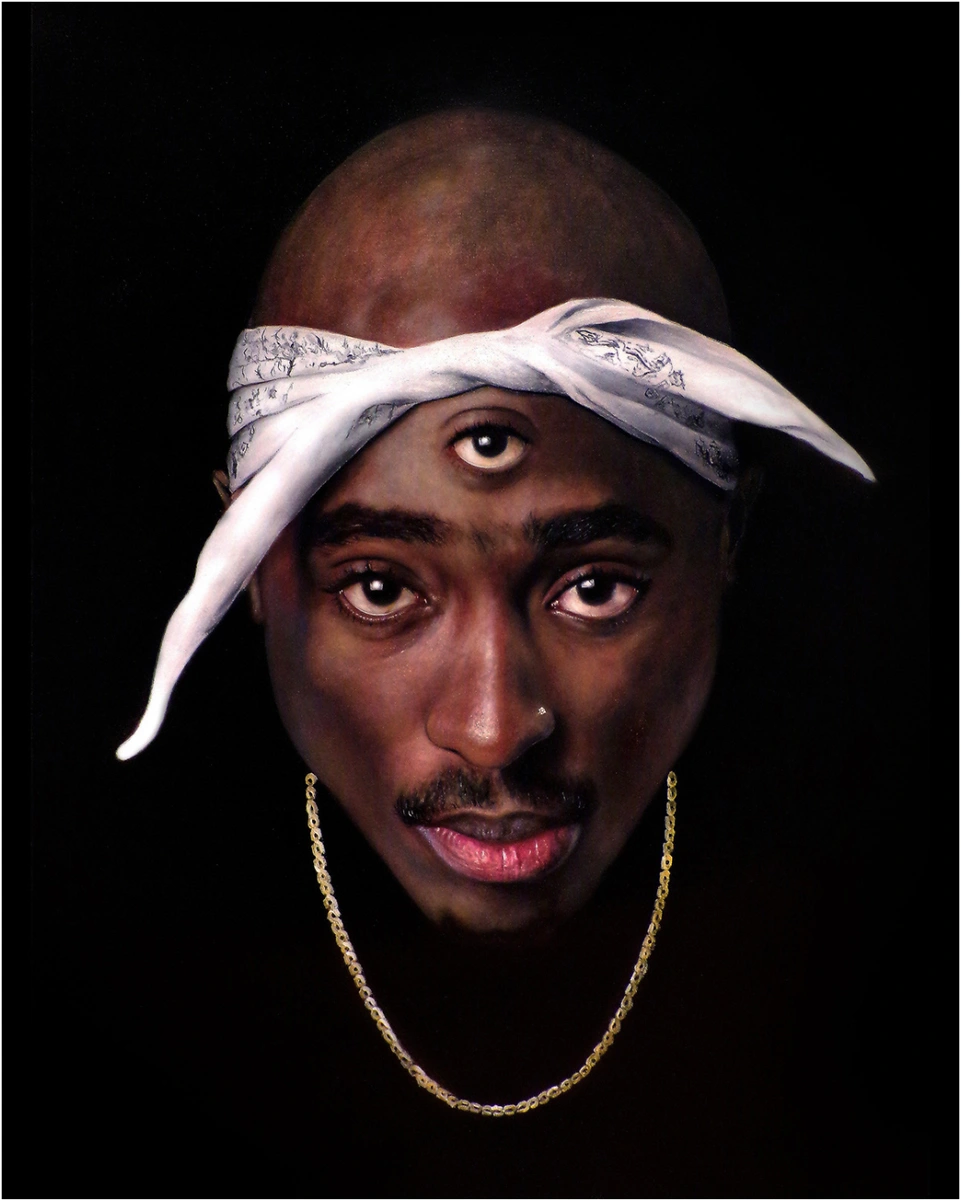

Alll Eyes On Me by Isaac Pelayo

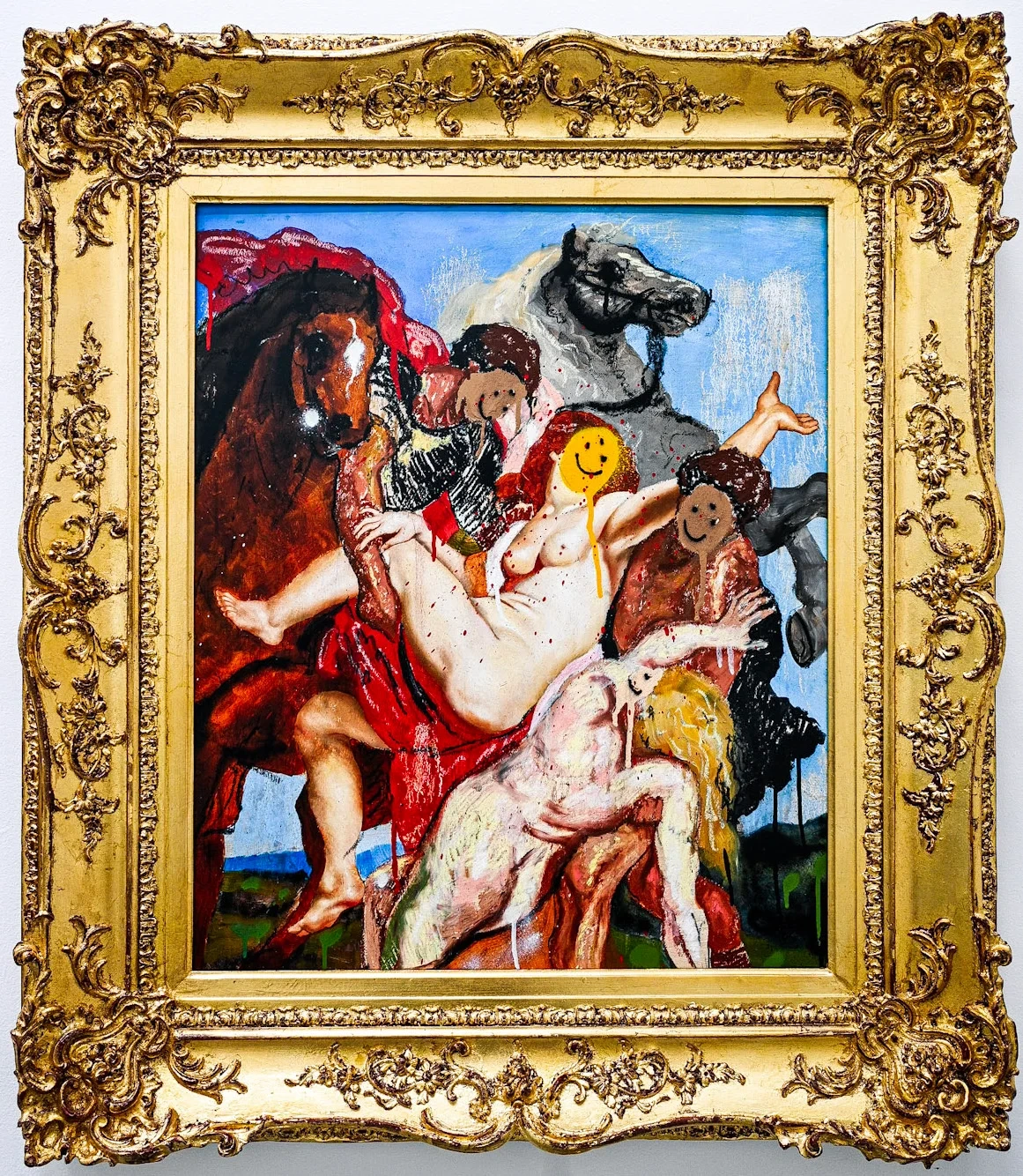

Only Fans by Isaac Pelayo

SP: To start, could you tell me a bit more about why and how you became an artist?

IP: Well, I started out as an artist. I’ve been doing art for as long as I can remember, and I’m 27 now. I think I’ve shown interest in art as early as two years old. I think by the time I was 10, I started exhibiting my work in gallery settings, and up until now, I’ve been exhibiting my work pretty consistently for 17 years. But I think the moment that I knew that it was something that I wanted to take seriously was probably when I was around 15 or 16. It was something that I really, really set my heart to. There were a lot of doubts and a lot of different sources of negativity around me, but that just forced me to dive deep into it, and I haven’t stopped since then.

SP: Art is a great outlet for expressing emotions and overcoming difficult times. Yours seems to be another story of how art became a catalyst for better things in life.

IP: For sure. It’s definitely been the most positive thing in my life. The environment I was in, art served as a guide in my life. Even to this day, without it, I honestly don’t know what else I would do. I’m not really good at anything else.

SP: It’s empowering to find that thing; it’s not just the thing you’re good at; it’s something that you’re passionate about, and that motivates you to keep going.

IP: Like I said, since I was a kid, I have always been an artist. I didn’t think I was going to be anything else.

SP: Was there a turning point, an event, or an experience that reaffirmed that you were on the right path?

IP: Not really, to be quite honest. When I was 15, I was bouncing around a lot, moving with my mom, and my dad was in L.A. So, the only time that I was exposed to art was when I went to see my dad on the weekends. Around that time, I moved to Texas and was there for a year. During that time, I got really good at making art. I was drawing in pencil, and I got pretty proficient in my technical skills. It was then that I started to feel like, “Okay, maybe I can do this”. It wasn’t just a fantasy. I had some talent. I had been selling my work since I was 10, so there was always this concrete understanding that I could actually make a living off of this shit. At 10 years old, you’re selling your drawings for 100 bucks, and for some people, that’s more money than they can make in one day.

Being an artist was something that I knew I could do, but I didn’t see true success until recently. By the time I was 18, I was really, really good at drawing. After high school, I went to college for a couple of years, but I dropped out cold turkey. When I dropped out, I decided to take on painting. I painted every single day for an entire year, and I got good fast. I gained a firm grasp and understanding of the use of oil brushes and oil paint and understanding how they worked. That’s when I started to see a shift in my career. When I was about 20 or 21, I started selling work fairly easily. I started making bigger works. I was making work a lot faster. I was making stronger work. It seemed like working with a pencil could only get you so far. So I turned to painting, and that’s when I started to find myself and find my audience. People responded to my painting more than my pencil drawings.

I would say that I saw actual concrete success during 2020. I had previously been hired to create an album cover and continued to be commissioned for a few more throughout that year, but I didn’t hit the success story until 2020. When we went into lockdown, I saw a massive influx of art sales. I probably sold around 100 paintings in 2020 alone. Then in 2021, I doubled that. The same thing in 2022. I would say 2020 was the year, the pivotal moment that I saw actual concrete success. Getting write-ups, participating in shows, and getting a lot of different celebrity collectors in my repertoire was all the result of making stronger work, work that I had never really made before.

SP: Thinking about how your style was based on this very fundamental practice, gaining the foundational skills of drawing and painting, you came to those so quickly. Then, hearing about your sales amidst the pandemic, it is obvious that you and your style are becoming more and more recognized. So, in your own words, thinking about the art you’re making now as well as your overarching practice, how do you describe your style of art making?

IP: I’m thinking about the question differently. I think the way that I make art, as opposed to visually, is not the style of what it looks like, but the process. It comes from something very personal. The best art that I’ve ever made, in my opinion, is art that comes from a place of heavy, heavy pressure and emotions. Whether it’s anger, sadness, anxiety, or depression. Whether it comes from a place of peace, zen, or happiness, I’m always teeter-tottering on the edge of breaking down. When I’m feeling all this pressure, with so much going on around me, I live right there when I make art. I’m pulling from so many different sources of emotion and experience, that it becomes a trance state. I’m just going along for the ride. That’s the style in which I create art.

Visually, my work can be described as a mixture of classical portraiture with the use of oil paint and brushes mixed with oil sticks, spray paint, and sometimes acrylic. The reason for that is, as a kid, I was always enamored by work that looked real—work that was classic, sophisticated. Growing up in L.A. and Riverside, there was graffiti everywhere. That took a heavy role in the work I make today. I started to think about the two types of work as separate entities that I wanted to bridge. Thinking about how the Renaissance period 500 years ago created works that were only available to a specific class of people, a high-class group of individuals, you had to be a royal, a noble, a duke, a cardinal, or a pope to be able to access artists of this skill and talent. 500 years ago, when you were around art, it was about status. Having art was about status. It was about money. It was about importance. Then fast forward, 500 years later. Street art was created by poor people. Street art was created by people who had nothing and went against the system. They wanted to say, “Hey, I’m here. I’m somebody. I exist.” So I am taking these two forms of making art, their different processes, and why they were creating this work, and trying to bridge them together.

I grew up around both situations. I grew up in the suburbs, and I grew up in the ghettos. Being around both rich and poor people, I got a taste of both lives. I found this obsession with wanting to bridge the gap between those two worlds. that don’t really belong together. But we’re not so different, and art is unifying to me. I didn’t grow up in the hood, so I can’t say I’m from the hood. I also didn’t grow up in Bel Air, so I can’t say I’m from this class of people. I didn’t have a place to belong. I always went back and forth, always on the edge of barely getting by. With my mom and dad, I grew up on welfare checks, food stamps, and Payless shoes. I started buying my own clothes when I was 13 or 14, making money on the side. I was selling art, doing jobs around the neighborhood, and I started to pay for my own shit.

The work that I create now, visually, is a mixture of all this stuff. The reason why I create it is because of how I grew up, the environment, the circumstances. I want to be able to create a conversation between all of those experiences. I’m sure there are people out there who grew up similarly and can relate. The work I make is definitely personal to me. I don’t make just anything, because it’s a pretty image, or it seems like a good idea. I have to have a personal connection to it; otherwise, I’m not going to find a place of deep, raw energy to drive the passion. If I can’t find that, I won’t make it. Every piece has a story as its backbone. Without one, it would not be a good work.

SP: Especially the emotions that you’re drawing from, coming out of the pandemic—it’s such a relatable set of emotions. People can pick up on that.

Your classical style, mixed with the essence of street art, exists in a liminal space, helping people appreciate art. There are two wildly different ideas of accessibility associated with each art movement. In their time, great pieces of Renaissance art were supported by wealthy patrons, and then watching the evolution of street art, going from an art form easily accessible for people to now finding its way into galleries today. I feel your combination of the two is a poignant mix.

IP: I think that I haven’t even begun to make the art I’m meant to yet. I’m just getting started.

SP: Within your style of art-making, you have a couple of different running motifs: the smiley face and the third eye. Can you explain how those came about and how you decide to employ them in different works?

IP: The third-eye concept was born in 2017. I started painting in early 2016, and by the time 2017 came around, I had gotten really good at painting portraits. I decided to paint a tribute portrait to Tupac, which I had always wanted to do, being from the West Coast and being a fan of music and Hip Hop. He was my idol growing up. I loved his music. I loved watching his interviews. I loved everything about the guy. He just seemed incredibly intelligent. At 17 years old, I remember seeing one of his interviews, and I was just impressed. I was enamored by this guy. He was a superhero. I wanted to do a portrait that was a little different from any other portrait I’d ever seen of Tupac before. I wanted to do something that was simple but bold, straight to the point, and in your face. So, I came up with the idea of depicting him with the third eye. It is symbolic of his aura, his attitude. Thug life was something that Tupac came up with. It wasn’t about being a thug and living that thuggish lifestyle, though. It was about not giving a fuck and projecting that same energy to the rest of the world. Living your life unbothered and living every day like it’s your fucking last. That’s some thug life shit. Standing your ground and being a warrior about everything. I wanted to paint his portrait to encompass all of that in one.

When I did his portrait with the third eye, it became very popular. Some of my friends reached out to me who grew up with Diddy’s kids, and they wanted a portrait of Biggie. So I did a portrait of Biggie in the same style. I ended up delivering it all the way from Vegas myself. The third eye was something that became really popular in my work. The same year, I got commissioned to do an album cover for a rapper from the East Coast. His name is Westside Gunn, and he became my biggest patron. Honestly, he is probably the reason for my continuous growing success. Every year, we’ve worked together, and we’ve created more and more. From album covers to t-shirt designs to art shows, he has connected me with different celebrity collectors—rappers and people in the Hip Hop world, the clothing world, and such. Then, in 2018, I had a show called “Vision” all about my third eye work. I did ten portraits of individuals that really impacted me growing up as a kid. Incorporating the third eye into simple portraits, they weren’t anything special or anything you’d know. They were visually different from one another; they all just had a third eye within highly rendered portraits.

Then, in 2020, when the pandemic happened, for about a month I didn’t paint at all. That was the very first month we went into lockdown. My dad moved into my one-bedroom apartment with me. I was stressed out. I was falling into a place of deep depression and anger. I got really drunk one day alone, and I just went ham on a canvas. I ended up painting a depiction of the Mona Lisa with a smiley face and a third eye. It was all very abstract expressionistic, Graffiti style background, and the hands were the only part that was rendered and realistic. When I posted that, people’s reactions were insane compared to any of my other work. People just ate it the fuck up.

It actually became an album cover for Westside Gunn. It became the alternate cover to his album “Pray for Paris” that Virgil Abloh designed. It was on vinyl, CDs, and cassettes. I got a lot of attention from that as well. So the smiley face thing took off in 2020, and I ran with it. It became a whole body of work that I created from 2020 to 2023. It became a heavily used motif in my work. I’m excited that people loved it and it resonated. But again, it was born in a place of anger, a place of stress, a place of anxiety, and a lot of pressure. I was tapped into a subconscious realm. I was a passenger. It came from a place that I really wouldn’t know how to describe, but I knew what I was feeling at that moment. The result turned out to be a positive thing.

Art by Isaac Pelayo | Photo courtesy of JM Art Management

SP: Those works are intriguing. There is such an emotionally driven resonance to it. You’re combining this realistic style, and even when it is rendered and naturalistic, as you mentioned, there is an expressiveness you are able to convey. I think that’s what strikes people. So having these motifs that are specific to you only elevates that. You are creating connections.

IP: It’s hard to even be me if I wasn’t including a little bit of something different. Anybody can paint; anybody can do what I do; that’s not hard. But to make art is very difficult. My job is to make work that is true to me, true to my personal experiences. Anyone can paint a pretty picture, but not too many people can transcend and move people. That’s what good art does. You transcend from one point to another, another place in time. That’s what I strive for. If it’s not moving you, it’s hardly considerable to call it art.

I’m not going to say that I’ve made art like that yet. I’m not going to self-proclaim myself as a prolific artist. That’s not what I’m focused on. I’m focused on making good work that’s true to myself, my vision, and what I stand for. Maybe then the art will do what it’s supposed to do. I don’t have to worry about that right now, though. I can just continue being me.

I feel like a lot of people these days make shit that’s just to make money. For me, I think about art as a gift. It was given to me, and I’m obligated to share it. It’s not for me. If art was for me, I wouldn’t be where I’m at today. I truly believe that there are a lot of people in the world who look at art as a way to make a paycheck or gain some sort of notoriety. But I don’t care for that shit. I never cared about attention, fame, or accolades. I’ve never really cared about who likes my work and who doesn’t. I make art for myself and those who appreciate it. That’s it. Everything else sort of falls into place, and I’m grateful for that. If I’m doing it for the wrong reasons, then surely I will be quick to fail, because half-assed shit doesn’t last long.

It is evident early on any time you talk with Pelayo that his practice, his career, and his passion for art are all derived from a pursuit of authenticity over superficiality. Painting from a place of genuine, personal expression elevates the ability of his work to connect with people in a lasting way, and that is what he has done so far in his career.

Photo of Isaac Pelayo by Castro Frank

The Geography and Genealogy of “Urban Symphony”

On June 6th, Pelayo is taking his work from Los Angeles to New York City with his inaugural exhibition on the East Coast. Taking place at the galleries of Inked Magazine, Pelayo is presenting a body of works in an exhibition titled “Urban Symphony”. The exhibition asks us to question the way we exist within our environments, especially urban ones. Looking at architecture and landscape with a lens of temporal disruption, the cacophony of the city fuses into a harmonious, synchronous display of intersecting cultures, histories, and people.

Amidst the layers of the work are glimmers of nostalgia. Perhaps it is the ability to see the world through Pelayo’s eyes, and maybe this is intensified by the inclusion of several never-before-seen pieces by his father, but the exhibition emanates a familiar sense of home. While filled with the echoes of countless unique voices, placing us within these urban symphonies, we watch them transform as each of our distinctive journeys influences what we see, the way we see, and how it defines the places we inhabit

SP: You have your first East Coast show coming up in New York this June called “Urban Symphony.” Tell us more about this exhibition.

IP: I titled the show “Urban Symphony” and it’s being held at a gallery called Inked NYC. It’s the headquarters for Inked Magazine, which is the tattoo magazine. I have a history of doing tattoos. I’ve done tattoos since I was 15. And in recent years, I’ve grown a relationship with the Inked Magazine team. Since their space serves as an art gallery as well, they asked me if I wanted to show my work. This was about a year and a half ago, and I turned the idea down until recently. I gave it some thought and said, Fuck it. Why not? I just didn’t know if I had the juice on the East Coast like I do in L.A. My last big show in 2022 had almost 1,000 people show up, and I sold a great deal of the work even ahead of the show. All by myself—no dealer, no art advisor, no funding, no media support. I had no real backbone; it was truly all me. After turning down the idea for the show with Inked, the idea grew on me. Also, my dad’s exhibiting a few works [in the show] as well. Kind of like a sub-exhibition alongside mine.

My show is about the concept of the rich and poor class. Taking inspiration from the Los Angeles landscape. Seeing the similarities in my travels. Traveling out of the country, going to Italy, and seeing 500-year-old churches covered in graffiti. Years of history, craftsmanship, and advertising layered and layered over years and years of decay, touched by so many different people throughout its life. In L.A., you go around downtown or east L.A. and you walk down the street from an Iglesia, a church, on a main street that is right next to a liquor store. You have a crude mural of the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ on the outside, while on top of it, there’s graffiti that the city is trying to cover it up, only for more graffiti to appear on top of it.

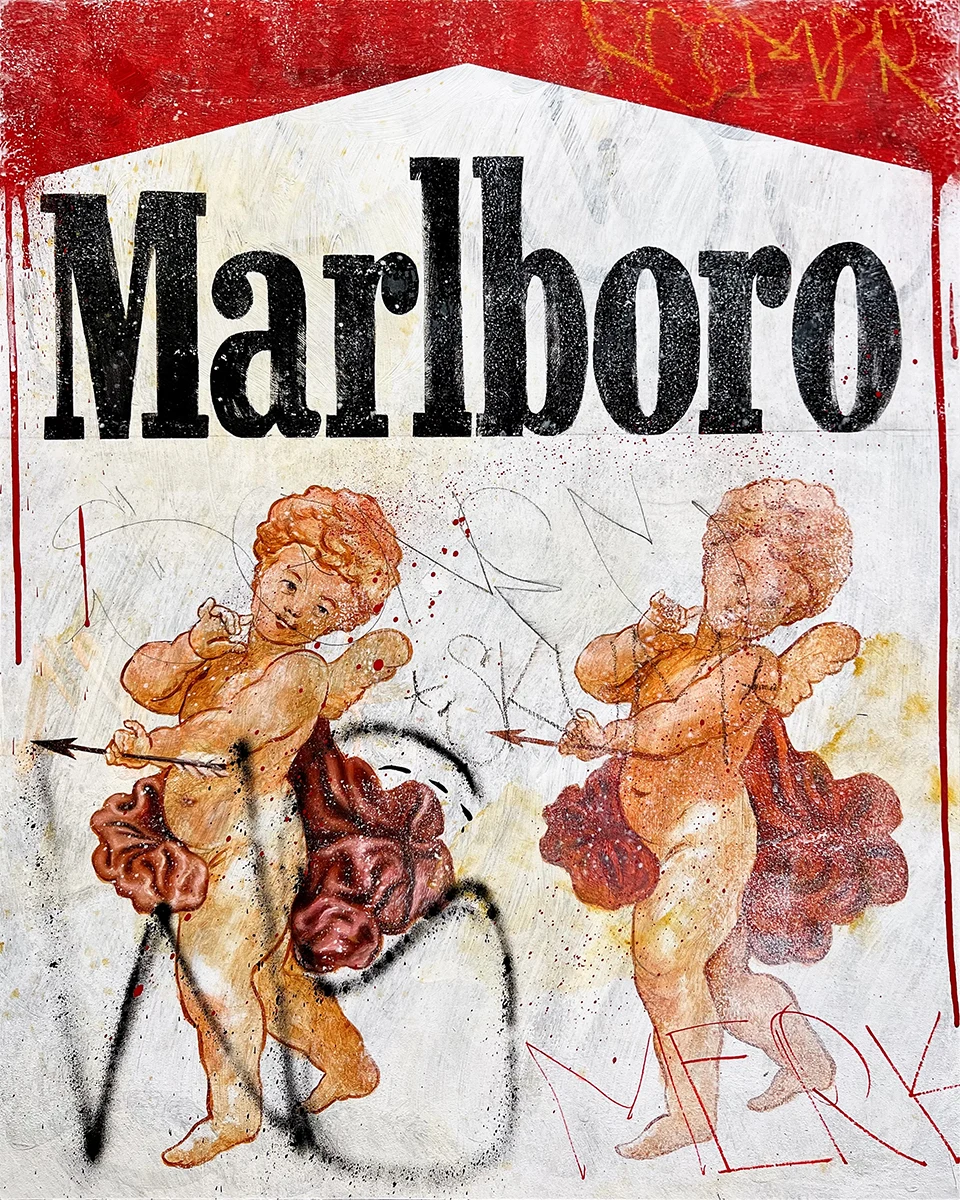

Marlboro by Isaac Pelayo

Then there’s advertising for cigarettes or some big corporation. It is a mixture of the rich and poor, people trying to survive amidst consumerism. A dialogue about being a buyer and seller. The show touches on this generation of people who come to America striving for something better. Then you have this newer generation, first- or second-generation Americans, who are angry with the government and the life around them. So they turn to the streets, maybe get into gangs, or maybe they’re street artists. They start expressing their identity through a visual representation projected on the public. In the public space, they are able to proclaim, I’m here, I exist, I’m somebody. All the while, corporate businesses that are gentrifying these smaller locations are throwing their big advertisements on the walls, making these places more modern. These places have been here for years and years, and now businesses are sweeping these poor people out. They don’t really give a shit. I grew up around that stuff. That’s why this work is true to my heart.

When I was a kid, I used to love taking long drives, staring out the window, and really taking in everything around me. Absorbing the landscape, the advertising, the colors, the textures of buildings. Looking at the graffiti and seeing how the city would cover them up. These are the things I would see on a day-to-day basis. It became a part of my everyday life—the visuals. Going from home to school, from home to work, or from home to a friend’s house—these are the things that you see every single day. They become part of your subconscious, like a subconscious splinter in your mind. It’s just there, and you don’t know why, but it becomes forever recognizable to you.

For instance, when I go to a city I’ve never been to before and I see graffiti and advertising on a liquor store, things that I grew up around, it almost makes me feel at home. There is something for us to latch on to and identify with. There are visuals that connect with certain people. If you grew up in these urban areas versus rural areas. Only poor people know about the lottery ticket system. Only poor people know about food stamps and EBT. Growing up in this environment, you recognize businesses like Cash for Gold. People are striving for big-name brands they can’t really afford, like Nike. Nike is big in the Mexican community. You always see people wearing Nike, and it’s probably been handed down, taken from the thrift store, or maybe it’s bootleg. You had to be part of that class of people to understand that shit. The work that I’m making now is reminiscent of that.

I’m incorporating imagery inspired by the Renaissance and Baroque periods as well. Using religious iconography not as a critique of religion but as a visual language prevalent in poor communities. The idea that only poor people go to church, only poor people really turn themselves to God. Rich people don’t concern themselves with such things. The art and imagery that I am painting were created 500 years ago. It was only available to the rich class, and I’m mixing it with this poor shit. I’m trying to unify everyone through art. I am saying that we are all sort of the same person, the same body; we just grew up in different spaces with different circumstances.

So the title “Urban Symphony” is a way to describe the environment over time. You look at an urban metropolis, and you think about the graffiti, the advertising, and all these small businesses. Everybody who lives in these cities, in these little communities has a hand in shaping the urban landscape. Construction through color, through advertising, and so on and so forth. It’s an orchestra. When you stand back and look at the city, it becomes this giant picture—a giant collaborative project that’s going to continue to change over the years with different people contributing. Adding more graffiti, the city trying to take it down, the city being weathered by rain and the heat of summers, new businesses popping up, new advertising, new religion. It is constantly changing. This work captures that.

SP: Is the work in this show going to consist of entirely new work, or will it be a mix of new and existing pieces?

IP: It’s all new work—10 to 15 pieces. I’m keeping the show really small. This is work that I have been creating since the end of 2023. I’m about halfway through creating the work for the show now. So I’m still creating different pieces as we speak, working on different concepts and different mockups. I’m trying to fine-tune the message and get the conversation down.

SP: You mentioned that there is going to be a sub-show of your father’s work. How do you envision that his work ties in with the work you are showing? Also, how does it feel to be having this show in tandem with him?

IP: The work that my dad’s showing is also very personal to him as a kid. My dad grew up in Mexico, despite being born in L.A. He moved back to L.A. at 19, got a job at Disney, and learned over the 30 years of his career. He kept incorporating what he learned from Disney with his own use of a pencil. He’s extremely proficient in pencil drawing and figurative work. So, he’s combining those two forms of making art to create a narrative about his upbringing in Mexico and his family migrating from Mexico to Los Angeles.

His work is sort of the backbone of my work. It’s talking about these communities that come from different countries and how they help shape these rural communities. He’s incorporating imagery like Superman. with a highly rendered portrait of one of his uncles wearing clothing from Mexico. The cartoon of Superman, when you were a kid in Mexico, was a fucking god. It was unlike anything you’d ever seen. All that American stuff. So his work definitely ties in with my work, thinking about how personal it is to our respective childhoods. The concept of what it means to grow up on a smaller scale and in a bit of a poor environment and circumstance.

SP: Thinking about “Urban Symphony” as a whole, when you have visitors come to this show, reaching a new audience now in New York, what are some of the ideas, thoughts, or messages you want them to take with them when they leave the exhibition?

IP: I hope that it creates new ideas and curiosity. Maybe the next time people walk these rural, urban communities, they’ll look at the landscape a little differently. They can look at it like art. They can appreciate it like they would the Mona Lisa. They could appreciate it like they would a museum. Maybe some of these corporate places can kind of slow down gentrification a little bit, preserve the essence of these urban cities and communities of color, and just cultivate that. You know L.A. serves as a total melting pot. for different cultures, ethnicities, and ideas. That’s what makes L.A. beautiful. New York is very much the same, if not even bigger or at least more congested. I would love for people to take this work and leave the exhibition, seeing the spaces around them differently. Maybe it sparks up some ideas or appreciation for these smaller businesses. Appreciate the people working hard to make it, to get by.

I can only say how I feel about the work. No matter what happens, once the work leaves my studio, it is out of my hands. I can’t say what anybody is going to feel about it or how they’re going to take it. I just hope that it inspires people, makes people feel at home, and gives them a sense of safety even when there is a little discomfort. Because I’m sure there’s a lot of people who relate. They don’t realize they’ve been looking out the window, looking at the same shit, and now they can appreciate it because it’s been shared in a new light.

SP: I can see that. Your work doesn’t seem like it’s proclaiming a statement in a way where you are forced to only consider one thing. It’s providing a space, a platform, for people to view the world around them and change their perceptions. It’s a space for them to reimagine.

IP: With this work, and with any work, honestly, I’m never telling people to think a certain way. I create room for new ideas, thousands of them, and I feel that’s the beauty of art. People will see and understand artworks based on their own personal experiences. People who grew up poor are going to see my work differently than those who grew up from a place of money. There are constantly going to be new ideas conceived from this work, and they’re all going to be different. The common denominator I envision for this body of work is that everybody can appreciate the urban landscape and environment. I want everybody to look at the landscape a little differently. Now I’ve planted seeds in people’s minds to go out and change the way they look at the city and everything else around them. I think that, in and of itself, is a powerful effect. If I can accomplish that, then I’m doing what I’m supposed to do.

We’re Only Scratching the Surface

For Pelayo, art has a power unlike anything else we know in the world. Transcending the literal nature of what we verbalize, the perceptions of our body language, and especially perpetuated mainstream ‘facts’, art encompasses something genuine. When Pelayo creates, this is the well he draws from. In keeping true to himself, his work has the undeniable capacity to resonate in the hearts and minds of others.

From body of work to body of work, an artistic philosophy of accessibility to art emerges. The act of viewing is something made available to everyone. What was once deeply personal undergoes a metamorphosis on the canvas, becoming a space of shared emotions that bridges the divides so often spotlit within our society today. With each iteration of a motif, a subject, or a series, he searches for original ways to tap into this fragile balance between the life of the artist and the collective experience. Pelayo finds himself eternally fueled by this need for reinvention.

SP: While I know your time is consumed with your upcoming show, creating these dozen works just for “Urban Symphony”; you mentioned early on that you were just touching the surface of what you want to do as an artist and the messages you want to convey. Do you have any plans, passions, or thoughts about new directions that you are interested in exploring?

IP: I think there are different aspects of making art. Beyond painting, I make clothing, I make music, I act, I model. So, if I’m not painting, I am always making art in some different way. It’s a really bold question, a loaded question, that I don’t have a definitive answer for you yet.

Over the last year, I have been battling with letting go. Letting go of who I am and what I’ve done for the last 20-plus years. I have been trying to find a place where I can shed the skin, shed this layer of thinking. I have been telling myself to grow into something new and bigger.

I feel like, after this show, I’m returning to a place where I can shed this skin and become a new person, become a new artist, become a bigger artist. More bright. More colorful. More creative. I’m focusing on learning to let go to make way for art that is more impactful. As I said earlier, I don’t think I’ve made the work that is really going to stand up through time, which leaves me excited for what’s to come. I’m leaving room for growth. It is like a sensei teaching young people in martial arts. If you know so much, your cup is already so full; how can you learn more? So I feel as though I need to empty my cup. Take the blinders off. Leave behind all these ideas and concepts that I see every day. Then I am able to grow into a new, better artist.

SP: One of the things I’ve picked up from chatting with you is how authentically intuitive you are with your practice. You know you’re coming from a place of emotion, not solely technical foundational sketches. Your work comes from a place that’s internal. It is exciting, as someone who works with artists and is an admirer of your work, to see what happens once you shed this skin and how your intuitiveness will manifest as you work towards this goal of creating art that will stand the test of time in your own eyes.

IP: Thank you, and I’m happy to share it with you. I’m happy to share it with the world. I’m happy to talk about it all. I love telling stories about my personal experiences and painting about them. As I’ve said, there is a power in art. It is a gift. It is for free. I feel art is obligated to be shared. When you are given a talent or a skill to create things that can move people, keeping it for yourself is selfish, and that is not something I want to be. I try to be selfless in sharing these stories, sparking up new ideas, and hopefully inspiring others.

The beauty of art is that it costs nothing to experience, and it can do so much for people. It can change the way people perceive, the way people think, and how they operate. It can almost change their genetic makeup, rewriting our pre-programmed presets. Art can reorganize people’s motherboards, and that’s dope. Even if they’re just a spectator.

SP: Art has the ability to build a community made up not just of artists and art enthusiasts; art really is for everyone, but many people don’t know that.

IP: Right. Art is everywhere. Art is in our daily lives. Art is in the clothing that we wear. It is in the way we speak. It is in the movies we watch, the music we hear, the landscape, the architecture, the food, the air we breathe, the very ground, and nature that we walk on. Art is anything that moves people. Art isn’t just a painting with oil and canvas or sculpture and marble.

Art happens the moment something is created. There’s a chemical reaction when a viewer looks at it. That moment when that person is changed. That moment is art. You can look at art as metaphysical—something that’s quantifiable. You create a painting, and it is hardly considered art if it just sits there and no one gets to see it.

Conversely, it can’t be considered art if people see it and are not changed by it. You have to have that reaction, that spark. It’s like putting a flame to gasoline. That moment of combustion is the art. Painting and sculpture, that’s just making things. That isn’t making art. Art fuels a combustion of emotion. In its inherent combustion, the universe itself is art.

Whether it be the Big Bang itself or the moment our eyes hit the canvas, according to Pelayo, art is infinitely being made around us. While still feeling he has so far left to go, we as viewers are left witnessing his artistic cycle, one of ongoing death and rebirth. He is on a journey of endless evolution, excavating the subconscious splinters festering beneath the surface along the way.

Portrait of Isaac by Castro Frank

The Subconscious Splinters of Isaac Pelayo 12

Like this project

Posted Apr 8, 2024

Los Angeles painter Isaac Pelayo is rethinking the foundations and philosophies of art making and, in doing so, taps into the human condition.

![The Art of Scotti Taylor [Artwork Descriptions]](https://media.contra.com/image/upload/w_400,q_auto:good,c_fill/zshfxoc082yyniiewtdf.avif)

![Andrea Mulcahy [Artist Bio]](https://media.contra.com/image/upload/w_400,q_auto:good,c_fill/dk10rp3vbtqoer6oej4o.avif)

![Joel Simon [Artist Statement]](https://media.contra.com/image/upload/w_400,q_auto:good,c_fill/hptoovi6nzii2zzcfz8z.avif)