Final Policy Recommendations & Insights

New Hampshire’s transportation system faces critical funding challenges that demand bold, data-driven policy action. Decades of underinvestment have left hundreds of bridges and miles of road in poor condition transportation.gov, while public transportation remains limited and underfunded (ranked 49th in the nation)advancetransit.comadvancetransit.com. With the influx of federal dollars from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) – including a 28% boost in highway funds and a 40% boost in transit funds transportation.gov– New Hampshire has a pivotal opportunity to close funding gaps and modernize its transportation network. This report presents actionable funding policy recommendations for both public transportation and highway/bridge infrastructure. Each recommendation is justified with benchmarking against peer states and aligned with state and federal priorities of improving access, equity, sustainability, and grant competitiveness. Key recommendations include:

Establish Sustainable Funding Streams: Implement legislative reforms to stabilize revenue, such as indexing the gas tax to inflation and dedicating new revenue sources to transit (e.g. vehicle registration fees or other dedicated funds). This will counteract the erosion of the Highway Fund nhfpi.org and address New Hampshire’s nation-leading underinvestment in public transitadvancetransit.comadvancetransit.com.

Maximize Federal Funding Leverage: Fully leverage IIJA funds by providing required state/local matches and utilizing flexible federal programs. New Hampshire should “flex” a greater share of federal highway dollars to transit projects, emulating Vermont’s practice of doubling transit funding by flexing 46% of its highway funds

transitcenter.org. Robust state match policies (including use of toll credits and general funds) will ensure no federal dollars are left on the table, mitigating past shortfalls.

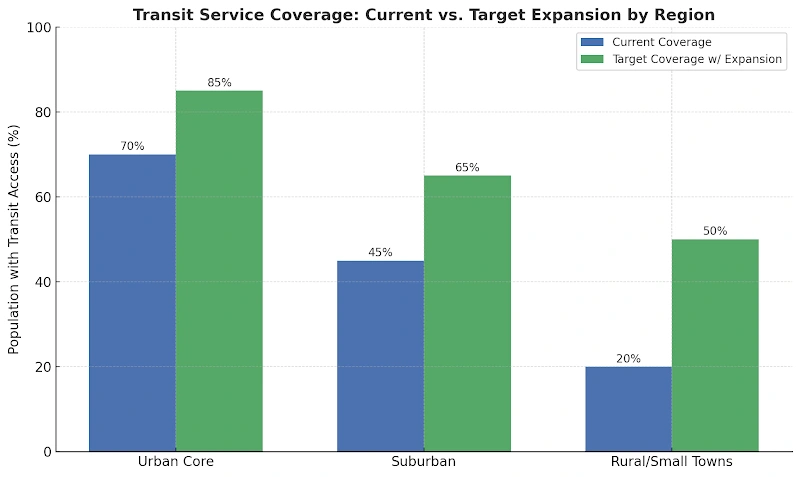

Enhance Public Transportation Access & Equity: Dramatically increase state support for public transportation operations and capital. A dedicated transit funding stream and higher annual appropriations (on the order of $5–$6+ million per year) are recommended to expand service coverage beyond the 34 communities currently served nhfpi.org, improve rural mobility, and better serve low-income and elderly populations. These investments will improve equity (transit riders in NH are disproportionately low-income nhfpi.org) and yield high economic returns (over 4:1 return on investment keepnhmoving.com keepnhmoving.com).

Strengthen Highway & Bridge Infrastructure: Prioritize maintenance and modernization of roads and bridges through stable funding and strategic use of federal programs. The state should reduce its reliance on one-time General Fund transfers

nhfpi.org by bolstering the Highway Fund – for example, modest gas tax increases or equivalent fees, as undertaken by 35 other states since 2013

ncsl.org. This will enable New Hampshire to clear its backlog of poor-condition bridges (215 as of 2021 transportation.gov) and improve road conditions while integrating resiliency and safety upgrades.

Improve Regional Coordination & Grant Readiness: Enhance coordination among state, regional, and local entities to plan and deliver projects more efficiently. Establish structures (e.g. regional transit districts or formal compacts) that pool resources and streamline service across jurisdictions. Invest in grant readiness by developing shovel-ready projects and providing technical assistance – boosting New Hampshire’s competitiveness for discretionary grants (such as federal bridge, transit, and safety grant programs transportation.gov). A small state match fund dedicated to matching grants can unlock significant federal investment.

These recommendations are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. By pursuing them in concert, New Hampshire can fully leverage unprecedented federal funding, build a future-proof transportation funding framework, and deliver a more accessible, equitable, and sustainable transportation system for all Granite Staters.

Introduction

New Hampshire’s transportation network is at a crossroads. Historically, the state has funded its highways, bridges, and transit systems at relatively low levels, relying heavily on federal funds and ad-hoc state support. The consequences of past funding decisions are evident today: infrastructure has deteriorated and transit services remain sparse, limiting access and economic opportunity. The American Society of Civil Engineers recently rated New Hampshire’s infrastructure a “C-” due to years of underinvestment transportation.gov. According to federal data, 215 bridges and 698 miles of roadway in New Hampshire are in poor condition transportation.gov, contributing to higher vehicle repair costs and safety risks. On the public transit side, only 34 of New Hampshire’s 234 municipalities have fixed-route bus service, and transit ridership accounts for just 0.7% of commute trips nhfpi.org. In 2019, New Hampshire ranked 49th of 50 states in per-capita support for public transportationadvancetransit.comadvancetransit.com– the lowest in New England, with essentially no state dollars for transit operationsadvancetransit.comadvancetransit.com. This limited transit network disproportionately impacts residents without cars, low-income workers, seniors, and people with disabilities nhfpi.org, raising serious equity concerns.

At the same time, there are major opportunities on the horizon. The 2021 federal IIJA (Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) is delivering a substantial influx of funding to New Hampshire: an estimated $1.4 billion over five years for highways and bridges (28% more per year than prior levels) and $126 million for public transportation (40% annual increase) transportation.gov. Additional federal grants are available for which New Hampshire can compete – from bridge modernization to transit capital, EV infrastructure, rural ferry service, and more transportation.gov transportation.gov. These funds come with requirements (typically a 20% state/local match for capital projects) and are governed by state policy decisions on how to allocate and utilize them. New Hampshire’s challenge is to convert this one-time windfall into lasting improvements by enacting state-level policies that provide the necessary matching resources, invest wisely in system upgrades, and set up stable funding beyond the life of IIJA.

This report synthesizes analysis of New Hampshire’s transportation funding trends and benchmarks them against peer states – from rural states like Vermont, Maine, and Iowa to larger states like Massachusetts, New York, and California. The goal is to identify best practices and actionable strategies that New Hampshire can adopt. The recommendations focus on funding policy mechanisms – such as revenue generation, dedicated funding streams, and match strategies – rather than specific construction projects. Crucially, the recommendations are designed to align with state and federal priorities: improved access and mobility, equitable service distribution, environmental sustainability (including emission reductions), and enhanced competitiveness for grants and economic development. By learning from peers and leveraging new funding tools, New Hampshire can craft policies to support both public transportation and highway/bridge infrastructure in a complementary way. The sections that follow detail the key recommendation areas, each with justification grounded in data and examples.

I. Sustainable Funding for Transportation: New Revenue & Reforms

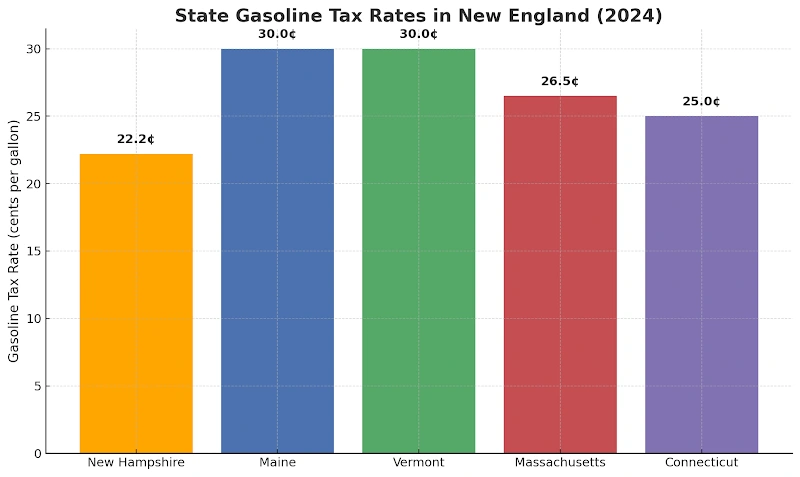

One of the most pressing needs is to reform and bolster New Hampshire’s transportation revenue streams. The state’s traditional funding sources – primarily fuel taxes (“road tolls”) and vehicle registration fees dedicated to the Highway Fund – have not kept pace with needs nhfpi.org. New Hampshire’s gasoline tax stands at 22.2 cents per gallon (unchanged since a modest $0.04 increase in 2014), and it is not indexed to inflation. As a result, inflation has steadily eroded the purchasing power of this tax, undermining the ability to maintain roads and bridges nhfpi.org. During the same period, many other states took action: 35 states and D.C. have raised or restructured their gas taxes since 2013 ncsl.org (often indexing them to inflation or fuel prices). New Hampshire’s neighbors, for example, have significantly higher fuel tax rates (e.g. Maine and Vermont at around 30 cents, and Connecticut/Massachusetts in the mid-20s), which translate into greater highway investment. To restore solvency and reduce reliance on one-time fixes, New Hampshire should enact legislative reforms to increase and stabilize its transportation revenues:

Index or Adjust the Gas Tax: Pegging the gas tax rate to an economic indicator (such as the Consumer Price Index or construction cost index) would allow revenue to keep up with rising costs ncsl.org. Even a one-time rate adjustment followed by periodic inflation adjustments would help close the growing gap. As of 2025, Mississippi, New Jersey, Minnesota, Utah and others have recently enacted such changes ncsl.org ncsl.org. New Hampshire can phase in a moderate increase and tie future changes to inflation, ensuring the Highway Fund grows alongside needs. This reform would address the current structural imbalance where General Fund dollars have been repeatedly needed to bail out the Highway Fund nhfpi.org. By securing a stable fuel tax, those general revenues could be freed up for other uses (or targeted to transit needs).

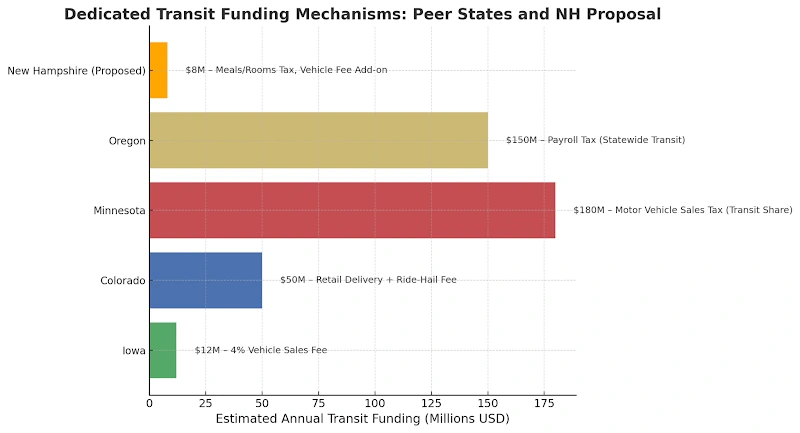

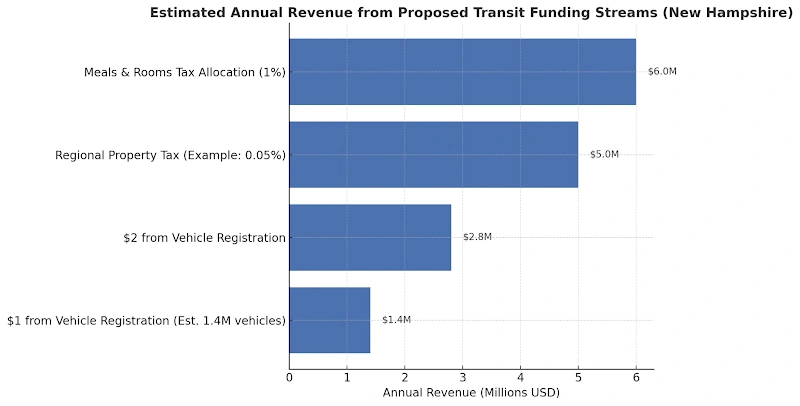

Implement Dedicated Multimodal Revenues: Because the New Hampshire Constitution restricts fuel tax and motor vehicle fees to highway purposes, the state must identify new revenue streams for public transportation. Many peer states have created dedicated funds for transit, often from sources like sales taxes, vehicle sales fees, or general fund allocations. For instance, Iowa devotes 4% of vehicle sales (new registration) fees to a State Transit Assistance program database.aceee.org, providing a steady source of transit funding. Another example is Colorado, which enacted a small fee on retail deliveries and ride-hailing, dedicating portions to a Multimodal Transportation Fund database.aceee.org database.aceee.org. New Hampshire should pursue a similar dedicated revenue mechanism for transit. Options include: a share of the state’s meals & rooms tax earmarked for a transit trust fund, a surcharge on rental cars or hotel stays directed to transit (leveraging tourism to fund mobility), or an increase in the existing $5 vehicle registration fee add-on that municipalities may charge for local transportation projects (RSA 261:153). In fact, allowing localities to double this fee (from $5 to $10) to specifically support transit service has been proposed as a solutionadvancetransit.comadvancetransit.com. Dedicated revenues would provide transit agencies the predictable funding needed to expand service and replace aging buses – which in turn improves access and sustainability.

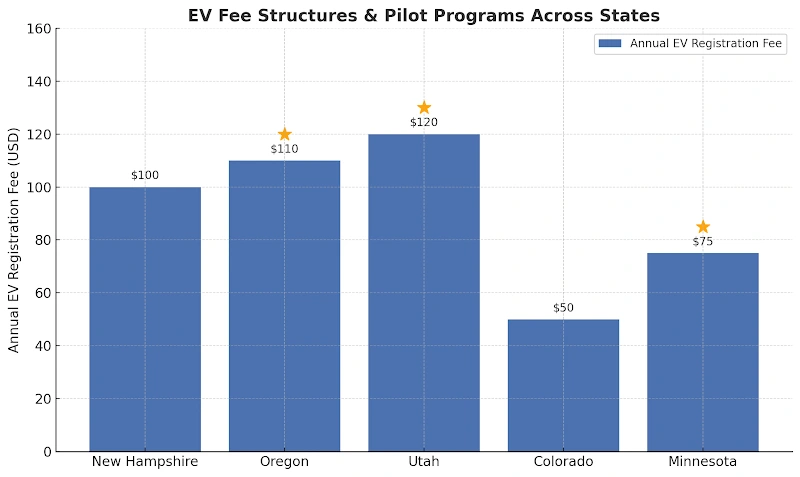

Enhance Electric Vehicle (EV) Fee Structures: With EV adoption accelerating, it’s vital to integrate EVs into the funding base so they contribute their fair share to road upkeep. New Hampshire took a positive step by approving additional annual registration fees of $100 for battery-electric and $50 for plug-in hybrid vehicles dover.nh.gov. The state should ensure these fees are reviewed periodically for adequacy and consider indexing them or moving to a mileage-based user fee pilot for EVs in the future (similar to pilot programs in Utah, Oregon, and other states). This will protect the Highway Fund as gasoline consumption declines, without unduly burdening EV owners. Revenue from EV fees (and any future road usage charges) should be dedicated to road and bridge maintenance, and possibly a portion to EV charging infrastructure, aligning with sustainability goals.

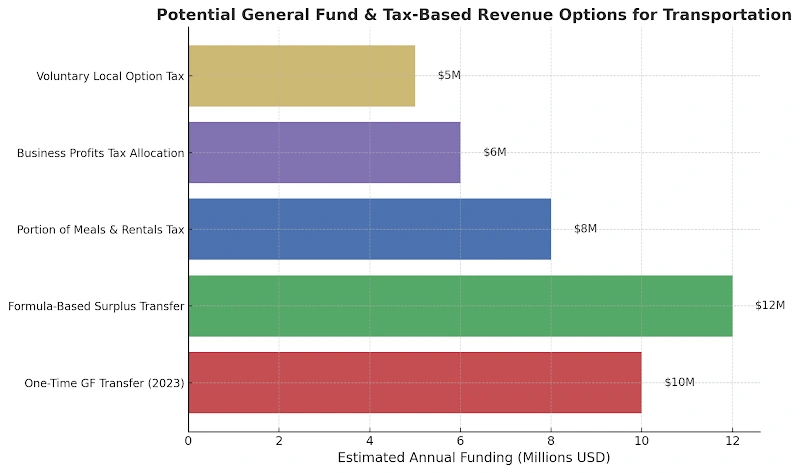

General Fund and Tax Policy Reforms: In the near term, the state’s healthy General Fund revenues (from sources like business taxes and real estate transfer taxes) nhfpi.org present an opportunity to invest in transportation. The current budget made a one-time transfer of $10 million from the General Fund to the Highway Fund nhfpi.org, but this ad-hoc approach can be improved. Policymakers could establish a formula-based transfer – for example, dedicating a small percentage of annual General Fund surplus to a Transportation Investment Fund. Such a mechanism, even if modest, would create a steady supplement for critical projects (including transit grants that cannot use highway dollars). Additionally, New Hampshire could examine its meals & rentals tax and business profits tax receipts for any opportunity to channel a portion into transportation infrastructure, given the strong connection between good transportation and economic vitality. Large states often use broad-based taxes to fund transit (Massachusetts dedicates a portion of its statewide sales tax to the MBTA, and New York uses taxes like a payroll mobility tax for the MTAadvancetransit.comadvancetransit.com). While New Hampshire lacks a sales tax, it could consider innovative analogues – for example, a voluntary local option sales or payroll tax in regions that want to invest in transit (with enabling legislation required). Any such tax structure should be designed with equity in mind (e.g. excluding essential goods if ever introduced, or offering rebates to low-income households for regressive fees).

In summary, creating sustainable funding streams is foundational. By enacting these revenue measures, New Hampshire will be equipped with the resources to match federal funds and make transformative investments. It will also distribute the funding burden more fairly – ensuring drivers (including EV owners) pay for road use, and tapping into general taxes for the broader public benefits of transit. Importantly, these steps realign New Hampshire with peer states that have already modernized their transportation funding. A well-funded system is the prerequisite for all other improvements in access, equity, and economic growth.

II. Maximizing Federal Funding: Leverage IIJA and Beyond

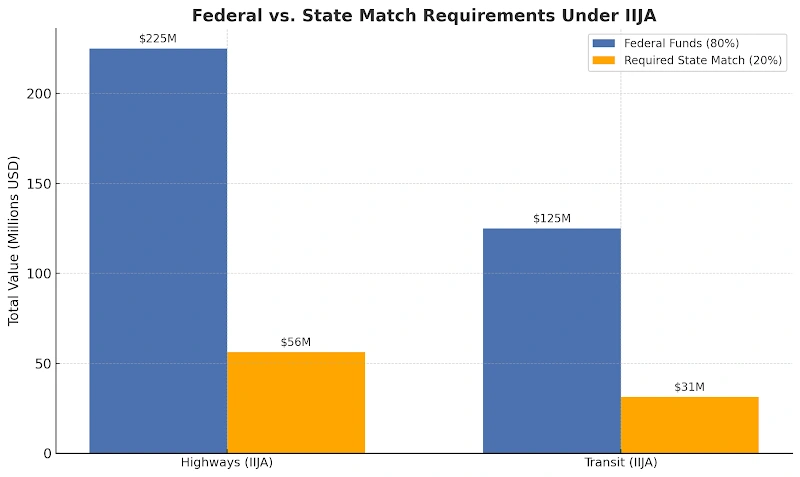

New Hampshire must fully leverage available federal funds – both formula allocations and competitive grants – to address its transportation needs. This requires proactive state policies to provide matching funds and strategically utilize flexible federal programs. In the past, New Hampshire has sometimes struggled with match shortfalls, leading to under-utilization of federal dollars (for example, transit agencies often rely on municipal funds and private grants for match, which can limit their ability to draw all federal apportionments nhmunicipal.org). With the surge of IIJA funding, the stakes are higher: every unmatched federal dollar is a missed opportunity to improve infrastructure at 80% federal discount. The following strategies will ensure New Hampshire captures the full benefit of federal aid:

Fully Fund State Match Requirements: Most federal highway and transit funds require a 20% non-federal match (although some bridge programs and safety funds allow higher federal share). New Hampshire should establish a State Matching Program that guarantees the availability of the 20% match for priority projects. This could mean reserving a portion of the Highway Fund or General Fund specifically for federal project matches, or using “soft match” where possible (e.g. toll credits). Toll credits are accrued when the state uses toll revenues for capital projects on its turnpike system, and can be applied in lieu of cash match for federal projects. States like New Jersey make heavy use of toll credits to maximize federal funds for transit and highway projects transitcenter.org. New Hampshire should similarly deploy toll credits earned through its Turnpike System to support projects (including transit capital purchases, which federal law permits using toll credits). By ensuring match funding, New Hampshire can confidently program the 28.3% increase in highway formula funds

transportation.gov and 40% increase in transit formula funds provided by IIJA. According to NHDOT, this federal boost equates to roughly $225 million extra for highways and $125 million for transit over five years businessnhmagazine.com – a significant expansion of resources if matched properly.

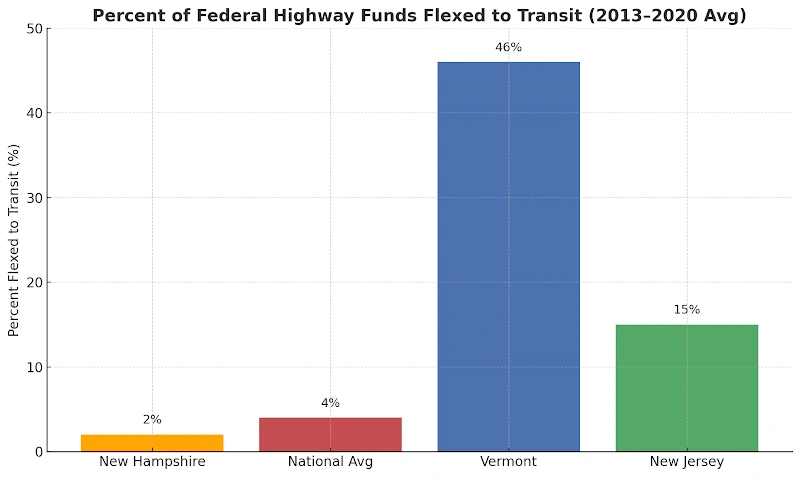

Utilize Flexible Federal Funds (STBG/CMAQ Transfers): Federal law gives states and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) considerable flexibility to transfer (“flex”) certain highway formula funds to transit uses. However, most states seldom use this flexibility transitcenter.org transitcenter.org. Between 2013 and 2020, less than 4% of federal highway funds nationwide were flexed to transit transitcenter.org. New Hampshire historically has been on the low end of flexing – likely under 2% – whereas several peer states demonstrate the benefits of flex funding. Vermont, for instance, has long used highway funds to support its extensive rural transit network, recognizing that its small population would otherwise receive insufficient transit funding transitcenter.org. From 2022 to 2025, Vermont plans to spend $205 million in federal funds on transit, of which 46% are flexed highway dollars transitcenter.org. This effectively doubles Vermont’s transit investment and helped it achieve a per-capita transit spending of $93 – higher than many larger states transitcenter.org.

New Jersey flexes about 15% of its highway funds to transit – the highest in the nation – using CMAQ funds for purchasing buses and rail cars enotrans.org enotrans.org. New Hampshire should set a goal to become a “superflexer” state (one of the top tier that flex >4% to transit transitcenter.org) by transferring eligible funds from programs like STBG and CMAQ into transit projects. For example, STBG funds could be flexed to help purchase electric buses for city transit systems or to fund intercity commuter bus routes, while CMAQ (Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality) funds could support new transit services that reduce traffic and emissions. This policy lever is especially powerful given New Hampshire’s constitutional funding constraints – flexing federal highway dollars does not violate the state’s ban on state fuel tax spending for transit, since these are federal funds being reallocated with federal permission. In essence, flexing is a way to fully leverage federal flexibility to meet New Hampshire’s unique needs: it can channel money to where it can have the greatest mobility and equity impact (such as rural transit for seniors, vanpools, park-and-ride facilities, etc.) without needing new state revenue. Coordination with MPOs will be key, as they often decide how to use STBG in urban areas – the state should encourage MPOs (like SNHPC in greater Manchester, etc.) to consider transit investments in their regional plans, offering technical support to identify eligible projects.

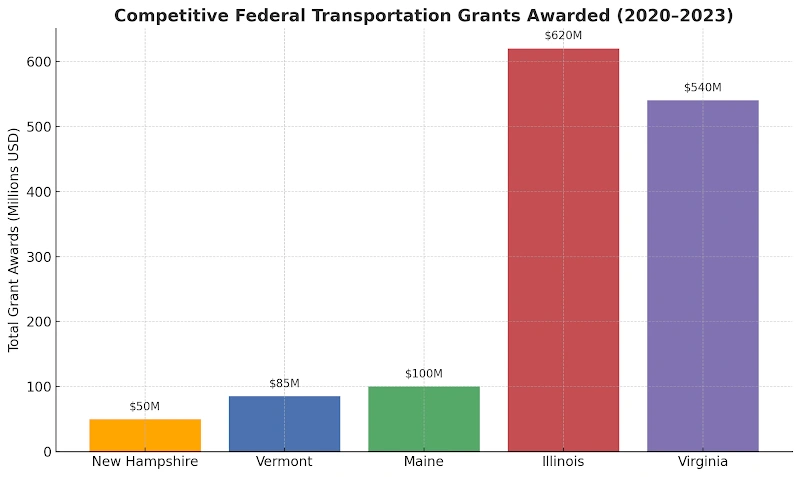

Prioritize Competitive Grant Pursuit: Beyond formula funds, IIJA and other federal programs offer billions in discretionary grants (e.g. the Bridge Investment Program, Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grants, INFRA grants for freight, Safe Streets for All for safety projects, FTA Capital Investment Grants for transit expansions, etc.). New Hampshire should adopt a grant readiness strategy to win its fair share of these highly competitive funds. This includes developing a pipeline of shovel-ready projects – for instance, advancing the design and engineering of high-priority projects (like bridge replacements or transit facility upgrades) to a stage where they can quickly be submitted for grant consideration. The state could create a dedicated “Grants Team” within NHDOT or the Governor’s office to coordinate applications, monitor upcoming grant opportunities, and work closely with regional partners on multi-jurisdictional proposals. In addition, providing state matching funds or bridging loans for grant awards will make local applications more attractive. If a city or regional transit authority knows the state will cover 20% of a project cost, they are more likely to apply for a federal grant to cover the other 80%. For example, a State Grant Match Fund could be established: whenever a New Hampshire municipality or agency wins a federal transportation grant, the state would commit to covering part of the required match (similar to programs in Illinois and Virginia that assist localities with matches). This incentivizes locals to seek grants and ensures no federal money is left unused due to funding gaps. The impact of such competitiveness is significant – New Hampshire can bring in additional tens of millions for transformative projects (e.g. station upgrades, new transit routes, major highway interchange improvements, greenway trails) that would otherwise be unaffordable.

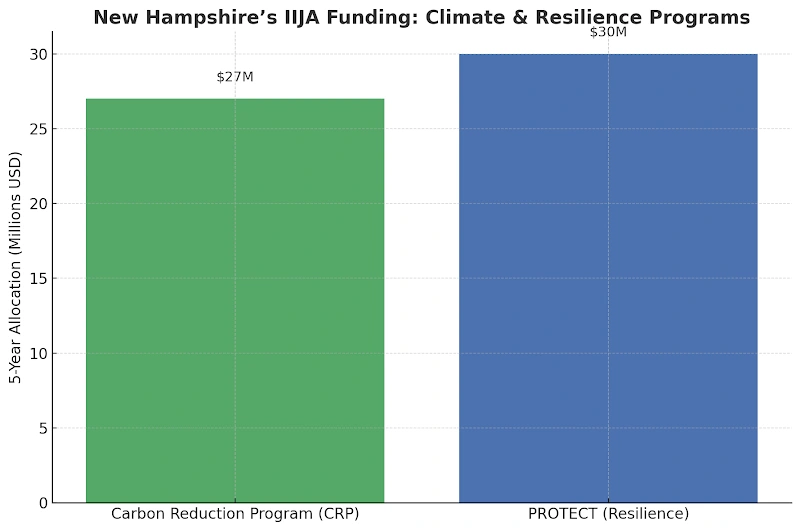

Leverage New Federal Programs for Innovation: IIJA introduced new formula programs, such as the Carbon Reduction Program (CRP) and PROTECT (resilience) funds transportation.gov. These come with flexibility to fund public transit, bicycle/pedestrian, and climate adaptation projects. The state should strategically use these programs in line with policy goals – for instance, using CRP funds to invest in electric vehicle charging infrastructure and fleet electrification, and using PROTECT funds to flood-proof critical roadways or improve drainage on state highways. Notably, New Hampshire is set to receive about $27 million over five years dedicated to reducing transportation emissions and $30 million for resilience transportation.gov. These could be directed toward projects like electric buses for transit agencies (emissions reduction) or reinforcing coastal roads against sea-level rise (resilience). By earmarking federal dollars to priority areas, the state can advance sustainability and climate goals with minimal hit to the state budget.

In summary, maximizing federal funding is about aggressively claiming what is available and aligning it with state needs. Every federal dollar carries the potential to stretch state and local funds further. Through assertive match funding, flexible transfers to transit, competitive grant campaigns, and strategic deployment of new federal programs, New Hampshire can substantially augment its transportation investment. This will accelerate improvements in infrastructure condition, expand transit services, and inject federal money into the local economy (supporting jobs and development). It will also signal to federal agencies that New Hampshire is an effective steward of federal funds – improving the state’s chances for future grants. The next section will delve into how these funds and new revenues should be directed, starting with public transportation enhancements.

III. Enhancing Public Transportation Access, Equity, and Sustainability

Expanding and improving public transportation in New Hampshire is a cornerstone of these policy recommendations. Robust transit service addresses multiple priorities: it provides access to jobs and services (economic opportunity), offers mobility for those who cannot drive (equity), reduces traffic congestion and emissions (sustainability), and even makes the state more attractive in competitive grant applications (by demonstrating multimodal commitment). Historically, New Hampshire’s transit network has been constrained by minimal state investment, fragmented local support, and a rural geography that poses challenges for service delivery. However, peer states prove that rural and small-town transit can thrive with the right support, and even large urban states offer models for funding transit operations at scale. Here we outline recommendations to bolster transit in New Hampshire, with justification from benchmarking and best practices:

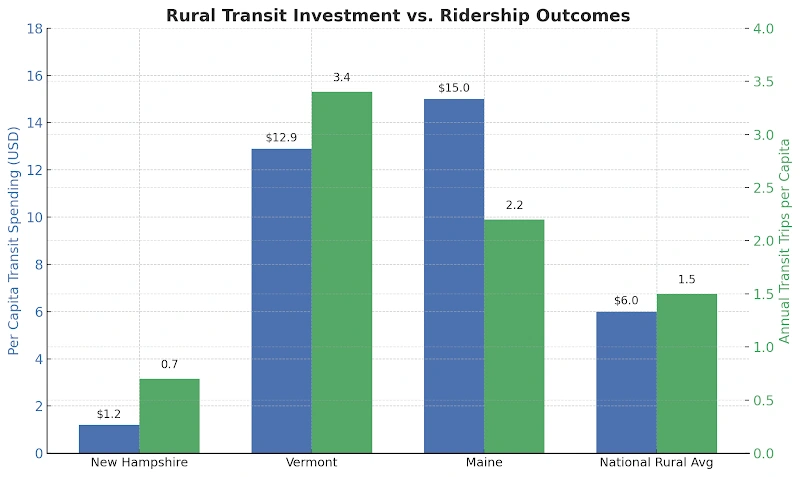

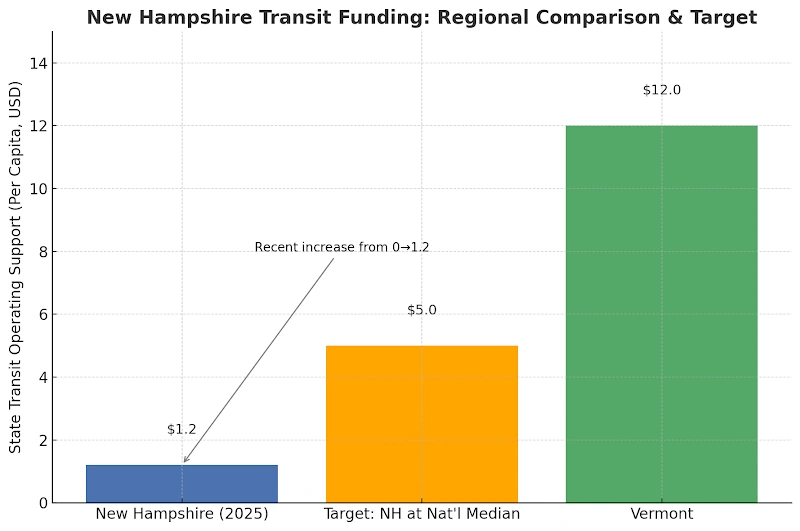

Substantially Increase State Operating Support: For many years, New Hampshire provided effectively $0 in state dollars for general public transit operations advancetransit.com, making it the only New England state without operating assistance. This changed modestly in the last budget: the state appropriated $600,000 in FY2024 and $1.68 million in FY2025 for transit operations keepnhmoving.com. The positive impact was immediate – transit providers expanded services and ridership grew by 18% in one year (2.1 million to 2.5 million trips) keepnhmoving.com. Building on this momentum, the state should boost transit funding to at least the national median on a per-capita basis over the next few years. The national median for state transit funding is around $5 per capitaadvancetransit.com, whereas New Hampshire is currently just over $1 per capita. Reaching the median would require roughly $6–7 million per year, given NH’s population. In fact, transit advocates have identified that $6.8 million per year in state transit investment could unlock an equal $6.8 million in federal funds (that are currently available but unused for lack of match), doubling the total impact keepnhmoving.com. This level of funding would still be modest compared to Vermont’s ~$12 per capita or Massachusetts’ $305 per capitaadvancetransit.com, but it would be transformational for New Hampshire – enabling longer service hours, more frequent buses on busy routes, and new routes to unserved communities. The return on investment is compelling: every $1 invested in transit yields over $4 in economic returns to the state keepnhmoving.com (through jobs, spending at local businesses by riders, increased workforce participation, etc.). Furthermore, transit investment leverages federal dollars at a 1:1 ratio in many cases keepnhmoving.com, essentially bringing “free” federal money to the table for each state dollar. Therefore, the recommendation is to establish a stable line-item in the state budget for public transit operations on the order of several million dollars annually (indexed for inflation), which would be distributed to transit providers statewide based on need and performance.

Create a Dedicated Public Transit Funding Stream: Beyond the annual budget appropriations, New Hampshire should pursue a dedicated funding mechanism for transit that grows over time. As discussed in the funding section, this could be a legislatively established Public Transportation Trust Fund receiving revenue from a new or existing source (e.g. a small portion of existing taxes or fees). Massachusetts and New York offer two models:Massachusetts’ Commonwealth Transportation Fund channels revenue from gas taxes and Registry fees into transit (with a portion specifically allocated to Regional Transit Authorities) massbudget.org, while New York’s MTA relies on dedicated taxes like a regional payroll tax and surcharges on ride-hailing. Closer to home, Vermont uses a combination of general fund appropriations and a portion of vehicle rental tax to fund transit (Vermont’s ~$7.9 million state transit funding in 2018 was partly general fund)advancetransit.com. New Hampshire could earmark, for example, a fraction of its vehicle registration fee (say $1 or $2 from each registration) into a state transit fund – given millions of vehicle registrations, this could yield a reliable funding pool for transit capital needs (buses, shelters, technology) and pilot services. Another approach is enabling county or regional transit levies: Iowa law allows counties above a certain size to form regional transit districts that levy a property tax for transit database.aceee.org. While New Hampshire does not have county-run transit, it could empower metropolitan regions (like Greater Manchester/Nashua or the Seacoast area) to hold referendums for a small supplemental property tax or fee dedicated to transit improvements in that region. Dedicated local revenue, combined with state matching grants, would significantly expand what transit agencies can do.

Expand Service Coverage and Frequency: With increased funding, the clear mandate is to deliver more service to more people, thereby improving access and equity. Currently, many communities have no public transit at all, and even in served areas, nights and weekends are often not covered. A policy goal should be to ensure that all regional population centers and rural hubs have some form of public transportation service, whether it’s fixed-route, flex-route, or on-demand. This can be achieved by supporting the growth of demand-response services in rural areas (leveraging FTA Section 5311 rural funds, which the state can match more fully) and by filling geographic gaps between existing transit systems. For example, the state could fund a connector shuttle between systems or support an expansion of service into a currently unserved county (perhaps through a competitive “service expansion grant”). In doing so, focus should remain on equity populations: low-income residents, older adults, individuals with disabilities, and rural residents with no car. The data shows public transit users in NH are far more likely to be low-income than solo drivers nhfpi.org, so expanding transit is inherently an equity strategy. Additionally, ensuring ADA paratransit services meet growing demand is critical – this is an unfunded mandate that strains transit budgets, so more state assistance here could maintain mobility for people with disabilities (which is both a civil rights issue and a quality of life issue).

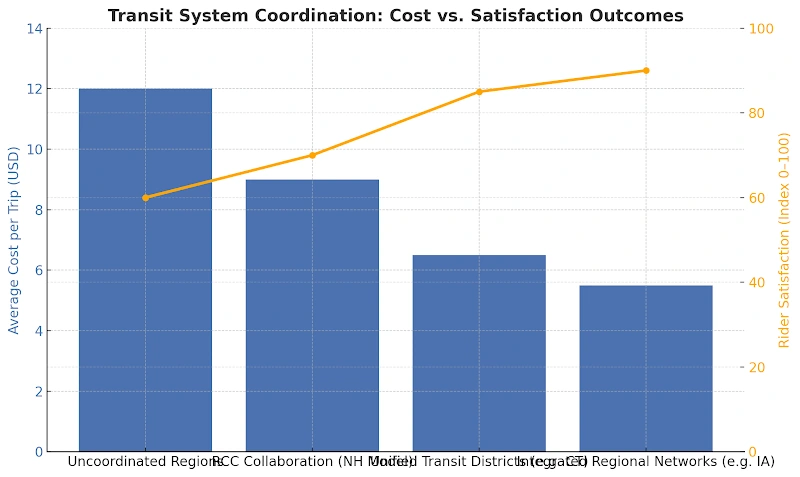

Enhance Regional Coordination and Efficiency: New Hampshire’s transit network is delivered by eight regional transit providers (a mix of public agencies and nonprofits) that collaborate through mechanisms like the Regional Coordinating Councils (RCCs) for community transportation. To maximize the impact of new funding, the state should strengthen these coordination efforts. Policy actions can include: providing funding for the RCCs to implement regional mobility programs (such as shared dispatch or volunteer driver programs), incentivizing transit agencies to consolidate services or enter inter-local agreements (if two adjacent systems can merge routes to eliminate a transfer, for instance), and supporting a statewide integrated fare system or trip planning system that makes using transit across regions easier. In peer states, regional coordination has shown success – Connecticutfamously merged 13 transit districts into a unified system in the Hartford area to improve efficiency, and Iowa’s regional transit agencies coordinate rural demand-response across county lines. New Hampshire could also explore forming a statewide transit authority or council that sets standards and distributes funds, while local entities operate service. At minimum, improving coordination will stretch dollars further and present a more unified “network” to riders. This is also attractive in grant applications: federal programs often favor collaborative, regional approaches to transportation challenges.

Promote Sustainable Transit Solutions: In line with sustainability goals, a portion of the investment should go toward “greening” the transit fleet and operations. This includes pursuing electric or hybrid buses (federal Low-No Emission grants are available, and with state match these could bring new electric buses to NH’s fleets), and incorporating first-mile/last-mile solutions like bike-share integration or microtransit in low-density areas. The state can assist by creating a bulk procurement program for electric buses and charging equipment (potentially in partnership with other New England states to get volume discounts) and by funding the installation of charging infrastructure at transit depots using the federal EV charging funds transportation.gov. Not only do electric buses reduce emissions, but they can lower operating costs long-term. Additionally, flexible service models (like on-demand shuttles or vanpools) should be funded to serve rural and suburban areas more efficiently than large fixed-route buses. This improves access for people in remote areas while keeping costs manageable – a win for both equity and cost-effectiveness. Finally, supporting transit-oriented development (TOD) through policy (working with municipalities to encourage housing and job growth near transit routes) can gradually boost ridership and make transit more self-sustaining.

By significantly boosting public transportation funding and smartly deploying it, New Hampshire can begin to close the gap with its peers and ensure transit is no longer an afterthought but a central part of its transportation system. The benefits will be far-reaching: workers will have affordable options to reach jobs, seniors will have mobility to remain independent, businesses will gain access to a larger labor pool, and the state will make progress on reducing traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, a demonstrated commitment to transit can raise New Hampshire’s profile in federal eyes, making the state more competitive for discretionary transit grants (such as FTA’s bus and facilities programs or potential future rail funding). It aligns with federal priorities of improving equity and sustainability in transportation transportation.gov.

IV. Strengthening Highway and Bridge Infrastructure for the Long Term

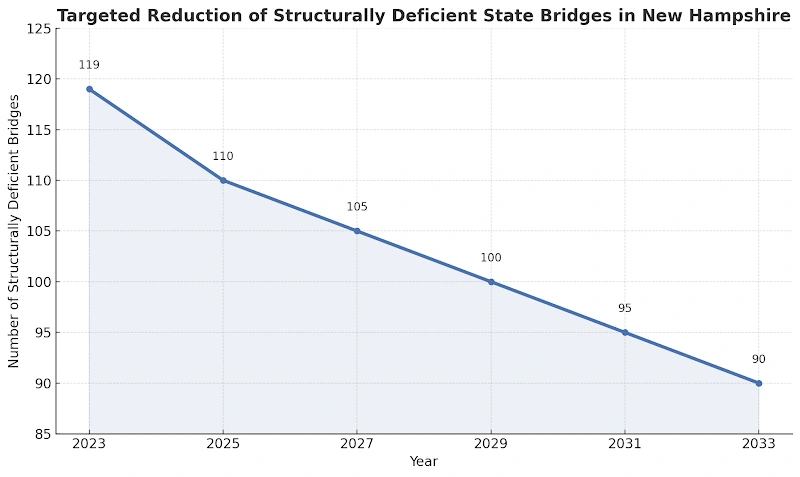

While investing in transit and multimodal options is crucial, New Hampshire’s roads and bridges will continue to carry the majority of trips and must be maintained in a state of good repair. The challenge is to do so in a way that is financially sustainable and forward-looking, incorporating modern best practices (like asset management, resiliency, and safety for all users). Historically, New Hampshire’s highway and bridge funding has been constrained, leading to aging infrastructure. As noted, over 200 bridges in the state are rated in poor condition transportation.gov, and certain categories of road (like local connector roads) have relatively high percentages in poor/very poor condition nhfpi.org. The state’s Ten-Year Transportation Improvement Plan, buoyed by IIJA funds, aims to reduce the number of “structurally deficient” state bridges from 119 in 2023 to 90 by 2033 nhfpi.org – an ambitious target that will require sustained funding and attention. Below are key recommendations to strengthen highways and bridges, ensuring that New Hampshire’s infrastructure meets the needs of residents and businesses now and in the future:

Maintain Stable and Adequate Highway Funding: As discussed in the revenue section, a top priority is to shore up the Highway Fund by adjusting gas taxes or equivalent fees so that routine maintenance and improvements are fully funded. The reliance on repeated one-time General Fund infusions (e.g. $50 million in 2022, $10 million in 2024) nhfpi.org is not a reliable strategy for the long term. By indexing the gas tax and exploring new revenue (like a road usage charge for EVs or moderate toll rate adjustments where politically feasible), the state can generate the estimated tens of millions in additional annual revenue needed to cover inflation and increased project costs. This stability will allow NHDOT to plan multi-year paving and bridge rehabilitation programs with confidence. In turn, better-maintained roads lower costs for drivers (New Hampshire drivers currently pay an extra ~$476/year in vehicle repairs due to rough roads transportation.gov) and improve safety. Recommendation: Legislate an automatic adjustment mechanism for the gas tax or an annually set highway user fee such that the Highway Fund grows at least at the rate of the construction cost index each year. Additionally, ensure the new EV fees are funneled into maintenance of the roads EVs use, as intended.

Invest Strategically in Bridge Rehabilitation and Replacement: Bridges are among the most capital-intensive assets, and New Hampshire has many that are decades old. With IIJA’s one-time $225 million bridge formula allocation businessnhmagazine.com, plus eligibility to compete for the $15 billion Bridge Investment Program transportation.gov, the state has a golden opportunity to significantly dent the bridge backlog. The recommendation is to prioritize the most critical structurally deficient bridges for immediate action, taking advantage of the increased federal share for bridge projects. IIJA allows federal funds to cover up to 100% of the cost for certain off-system (municipal) bridges – New Hampshire should help municipalities by tapping this provision, essentially fixing local bridges at no local cost. For larger state-owned bridges, the state should package them into competitive grant applications (for example, a proposal to replace several aging Connectors on I-93 or a major river crossing) and be prepared with the 20% match. Strategically, focus on bridges that, if closed or load-posted, would cause major economic disruptions – these yield high benefit-cost ratios. The state’s 10-year plan already lists bridge priorities; this should be regularly updated with the latest inspection data and climate resiliency considerations (e.g. making sure new bridges are built higher or stronger to withstand floods). Aim to eliminate the worst of the “red list” bridges by the end of the IIJA period, which appears feasible with diligent effort and matching funds.

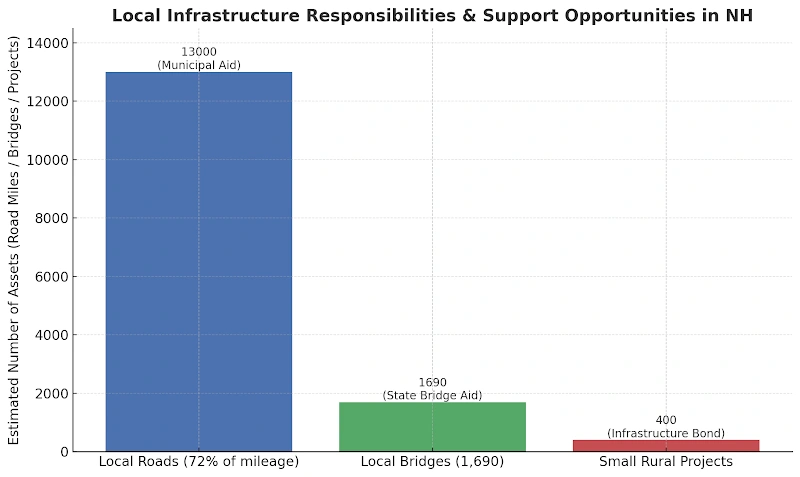

Support Local Roads and Bridges: New Hampshire’s local governments maintain 72% of the road mileage in the state nhfpi.org and about 1,690 local bridges nhfpi.org. Many rural towns struggle to afford needed repairs due to small tax bases nhfpi.org. The state has in the past provided supplemental municipal aid (like a $20 million one-time aid in the 2024-2025 budget) nhfpi.org. Going forward, a more systematic approach to aiding local infrastructure is recommended. This could be in the form of an annual Municipal Transportation Grant program that helps towns pave local roads or fix small bridges, especially if they can’t easily access federal aid. Another approach is to expand the existing State Bridge Aid program (which splits costs with towns) by increasing its funding and expediting project delivery. Ensuring rural communities aren’t left behind aligns with equity – residents in those areas depend on road connectivity for basic access. It’s worth exploring whether a share of the state’s General Fund surplus or a bonding program could be devoted to catching up local infrastructure needs (perhaps as a one-time “Community Infrastructure” bond that towns could tap for matching funds). Better local roads also contribute to the overall network’s efficiency and safety.

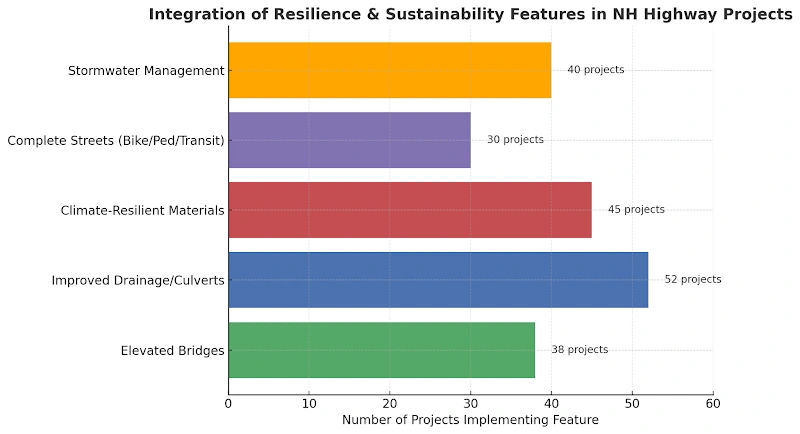

Integrate Resilience and Sustainability in Highway Projects: The effects of climate change – heavier precipitation, extreme storms, freeze-thaw cycles – are stressing New Hampshire’s roadways and bridges nhfpi.org. It is vital that new investments be made with resilience in mind, to avoid future costly damage. Using the federal PROTECT funds and other resources, the state should incorporate features like improved drainage, higher bridge elevations, and more durable materials in reconstruction projects nhfpi.org. For example, when rebuilding a flood-prone rural road, add larger culverts and stabilize the surrounding soil. NHDOT should update design standards to account for projected climate impacts over a structure’s lifespan. In addition to resilience, sustainability and complete streets principles should be included: whenever a road is resurfaced or redesigned, evaluate whether accommodations for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit (bus stops, etc.) can be added. This aligns with federal policy (IIJA explicitly focuses on safety for all users and climate mitigation transportation.gov) and state goals of reducing traffic fatalities. New Hampshire could adopt a state Complete Streets policy requiring that the needs of non-driving users are considered in all projects on state roads. While not directly a funding policy, this ensures that the funding we do spend yields multi-modal benefits and safer, more livable communities.

Plan for Future Growth and Strategic Expansions: Most of the focus is rightly on maintaining existing infrastructure, but there are cases where strategic highway expansions or new infrastructure may be warranted (for instance, addressing major bottlenecks or connecting emerging economic centers). New Hampshire’s seacoast and southern tier have seen growth leading to congestion on key corridors. The state should use performance data and travel demand models to identify if/when capacity enhancements are needed, and plan them in a fiscally responsible way. This might include selective widening of I-93 (with federal Interstate grant help), new interchanges to improve access and safety, or projects like the oft-discussed commuter rail extension to Boston (which, while a transit project, involves significant infrastructure investment and coordination with highway networks like park-and-rides). For any major expansion, ensure there is a solid funding plan – potentially using tolling or public-private partnerships if appropriate. For example, if a new lane on a turnpike can be financed through toll revenue bonds, that should be considered to avoid diverting funds from maintenance. The key is to balance expansion with maintenance so as not to create more assets that can’t be upkept. One idea is to adopt a “fix-it-first” policy, where the state commits that at least (say) 80% of available highway funds go to rehab and modernization, with no more than 20% to expansions. This mirrors policies in states like Massachusetts that emphasize state of good repair.

By implementing these measures, New Hampshire will strengthen its highway and bridge infrastructure in a sustainable manner. A well-maintained road network is fundamental for access – it ensures that people and goods can move reliably. It also supports economic development, as businesses require efficient freight routes and attractive commuting conditions for workers. Importantly, these recommendations incorporate equity (helping rural and small-town infrastructure) and safety/environmental improvements (complete streets, resilient design), thus aligning with broader transportation goals beyond just pavement and steel. As the state modernizes its funding approach, it can achieve a virtuous cycle: better infrastructure leading to economic growth, which in turn generates revenue that can be reinvested.

V. Improving Regional Coordination and Grant Competitiveness

Transportation challenges often cross city and town boundaries, requiring a coordinated regional approach. Additionally, succeeding in complex grant applications or major initiatives (like expanding intercity rail or rolling out intelligent transportation systems) often demands collaboration among multiple stakeholders. New Hampshire should bolster regional coordination structures and actively cultivate partnerships to maximize efficiency and access new funding streams. In many ways, this is about governance and planning improvements that complement the funding injections described earlier. Key recommendations in this realm include:

Empower Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and Regional Planning Commissions (RPCs): New Hampshire’s MPOs and RPCs already play a role in prioritizing projects for federal funding in their areas. The state should lean into this regional planning model by giving these bodies a stronger voice and resources to develop regional transportation strategies. For instance, the state can allocate a portion of funding to each region (formula-based on population or road miles) and let regional planners recommend how to split it between highway, transit, bike/ped projects, etc., in alignment with local needs. This approach, similar to Massachusetts’ practice of regional TIP (Transportation Improvement Program) development, ensures local buy-in and can surface innovative solutions (like a region deciding to flex more STBG to transit if that’s a priority). Additionally, providing technical support to MPOs – perhaps through a central State Planning Assistance Program – can improve the quality of regional plans, making them more competitive for federal discretionary grants. When a region has an integrated vision (say, a combined highway upgrade + transit enhancement + trail project), it can pursue federal grants that reward multi-faceted, multi-jurisdictional efforts.

Formalize Regional Transit Authorities or Districts: Building on the earlier coordination discussion, New Hampshire may consider enabling legislation for Regional Transit Authorities (RTAs). An RTA could be a quasi-governmental entity covering a group of municipalities, with the ability to receive state/federal funds and even levy fees (if approved by voters) for transit. This is the model in Massachusetts, where 15 RTAs serve different regions, funded by state contract assistance and local assessments massbudget.org. In New Hampshire’s context, existing transit providers could evolve into RTAs with more secure funding. For example, the communities served by COAST in the Seacoast could band together under an RTA structure, allowing for a fair sharing of costs and a unified governance. The state’s role would be to provide seed funding and match, while municipalities could contribute via a formula or dedicated local fees. RTAs would facilitate regional decision-making for transit (no one town can veto service expansions that benefit the region) and could take on functions like region-wide marketing or integrated scheduling. Over time, this could lead to more coherent service across the state, easier fare payment (one pass for multiple regions), and a stronger case for funding – both state and federal – because regional entities can demonstrate broader impact.

Regional Collaboration on Highways and Land Use: Regional coordination isn’t only about transit. Many highway and bridge projects span jurisdictions (e.g. a bridge connecting two towns, or a corridor that runs through a region). The state can encourage regions to identify their top inter-municipal transportation needs and come up with cost-sharing agreements or joint advocacy. For instance, if several towns along a congested route agree on the need for a bypass or a series of roundabouts, they can collectively lobby and perhaps co-fund preliminary studies, which strengthens the project’s viability. The state’s regional planning bodies should facilitate these conversations and help bundle smaller projects into bigger, impactful programs. This also touches on land use – transportation is most effective when coordinated with where housing and jobs are located. New Hampshire could support regional studies on transit-oriented development or corridor land-use planning (something the RPCs could lead with a small grant). By aligning land use and transportation on a regional level, investments will yield better long-term results (for example, a new transit line will get more ridership if affordable housing is developed along it in multiple towns).

Dedicated Office or Task Force for Grant Strategy: To boost grant competitiveness, the state might create an Interagency Grant Task Force that includes representatives from NHDOT, the Department of Environmental Services (for any waterway or air quality related transportation grants), Department of Business and Economic Affairs, and local experts. The task force’s job would be to identify grant opportunities (across DOT, EPA, Commerce, etc.) that can benefit NH transportation, and to assemble strong multi-partner applications. For example, a grant for a “Complete Streets” corridor improvement might involve NHDOT (road redesign), the local transit agency (bus stops), the town (sidewalks zoning changes), and an advocacy group (public outreach) all working together. Having a formal structure to coordinate these efforts ensures nothing falls through the cracks. New Hampshire has done well with some grants – e.g., securing funding for the expansion of I-93 and for airport improvements – but a more systematic approach could increase the hit rate, especially for new programs in IIJA related to safety, resilience, and equity. The task force can also engage private sector and institutions (like universities) where relevant, to bolster applications with additional funding or expertise.

Public-Private Partnerships and Innovative Financing: Regional coordination can extend to working with the private sector on transportation solutions. For instance, large employers or tourist destinations in a region might partner with transit agencies to fund shuttles (such as ski resorts supporting seasonal bus routes). The state can facilitate these partnerships by providing matching funds or frameworks (e.g., a “community mobility partnership” program that matches private contributions for transit service extensions). On the infrastructure side, if there’s a critical regional project like expanding a turnpike interchange near a business park, a public-private partnership (P3) could be explored where a private entity fronts some capital in exchange for toll revenue or development rights. While P3s are not a panacea, in certain cases they can bring in additional resources and innovation. The key is to have enabling legislation that protects the public interest (transparency, fair pricing) while allowing negotiated agreements. By inviting private and regional stakeholders to co-invest, New Hampshire can stretch its dollars further and show grant reviewers that projects have broad backing.

In conclusion, improving regional coordination and grant readiness is about breaking silos – between jurisdictions, between modes, and between public and private sectors. Transportation does not stop at town lines, and neither should our solutions. A more regional outlook will lead to services like transit that seamlessly cross city lines, or highway projects that consider the entire corridor’s needs, not just piece by piece. It will also position New Hampshire to punch above its weight in obtaining competitive funds, as collaborative proposals often score better. Ultimately, the residents of New Hampshire benefit from a well-coordinated approach: whether it means a smoother commute, a new bus route that connects two regions, or federal dollars funding a project that otherwise would sit idle.

Conclusion

New Hampshire stands at an inflection point in transportation policy. The outlined above provide a comprehensive roadmap for moving the state’s transportation system into a new era of stability, accessibility, and resilience. By adopting sustainable funding mechanisms, the state can break the cycle of reactive, one-time fixes and instead establish a dependable flow of investment for infrastructure. By leveraging every available federal dollar and encouraging flexibility in funding, New Hampshire ensures that it maximizes value for its taxpayers – securing improvements at 20 cents on the dollar in many cases, thanks to federal matches. Crucially, by significantly increasing support for public transportation and embracing multimodal solutions, the state addresses long-standing gaps in access and equity, ensuring that mobility is not a luxury but a reality for all residents, including those in rural areas, those of limited means, and those who choose alternatives to driving.

These recommendations are informed by the successes and lessons of peer states. From Vermont’s creative use of federal funds to boost rural transit transitcenter.org, to Massachusetts and Iowa’s development of dedicated transit funding and regional governanceadvancetransit.com database.aceee.org, to New Jersey’s strategic investment of toll revenue into transit transitcenter.org – New Hampshire has many models to emulate while tailoring them to our unique context. Large states demonstrate that bold investment yields dividends (for example, Colorado’s recent dedication of multi-million-dollar funds to transit and active transportation database.aceee.org), and small states prove that you don’t need a huge population to support effective transit and well-maintained roads (witness Maine and Vermont steadily improving their systems). By benchmarking against these peers, New Hampshire can set realistic yet ambitious targets: perhaps aiming to move from 49th in transit funding closer to the 30s within five years, or to reduce the percent of roads in poor condition to under 10%. Clear goals, backed by the policies recommended here, will allow progress to be measured and reported to the public – enhancing transparency and accountability.

Alignment with federal and state priorities has been a consistent theme. The recommended policies directly support federal emphasis areas like equity (through expanded transit access for underserved groups), sustainability (through investment in transit, EV infrastructure, and emissions reduction) and safety (through complete streets and improved road conditions). They also dovetail with New Hampshire’s own goals of economic growth and quality of life: a stronger transportation network means faster movement of goods, better access to tourist destinations, and an edge in attracting employers who value infrastructure. Additionally, implementing these funding policies can have multiplier effects, such as job creation in construction and transit operations, and reduced long-term costs as we shift to more preventative maintenance.

Finally, it is worth noting that these recommendations are actionable – many can be initiated through legislation in the next session or via policy changes at NHDOT. For example, a bill to index the gas tax, a budget line-item for transit ops, or an executive directive to MPOs to consider flexing funds are all concrete steps that could happen in the short term. Others, like establishing a dedicated transit fund or regional transit authorities, might take longer due to required studies or consensus-building, but starting the conversation now is imperative. The report has highlighted that doing nothing is not a viable option: continuing the status quo would mean leaving federal money unused, watching infrastructure further deteriorate, and falling even further behind neighboring states in mobility offerings. In contrast, the recommended actions offer a path to a more robust, equitable, and future-ready transportation system for New Hampshire.

In summary, by implementing the Final Policy Recommendations & Insights detailed above, New Hampshire’s leaders can ensure the state seizes this moment of opportunity. The investments and policies proposed are not just expenditures; they are investments in New Hampshire’s future – its economy, its communities, and its environment. With thoughtful implementation, the Granite State can build a transportation network that is second to none for a state of its size, proving that even with limited resources, smart policy and collaboration can deliver outsized results. The time to act is now, to set New Hampshire on course for decades of mobility and prosperity to come.

Sources & Bibliography

New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI)

Transportation.gov – U.S. Department of Transportation

Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL)

Advance Transit & Keep NH Moving Coalition

TRIP – National Transportation Research Nonprofit

TransitCenter.org

AASHTO – American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

Business NH Magazine

Coordinating Council on Access and Mobility (CCAM) – Federal Interagency Council

Urban Institute

DOT NH – New Hampshire Department of Transportation

Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency (DSIRE) & ACEEE

Like this project

Posted Apr 9, 2025

State Of New Hampshire Department of Transportation Final Policy Recommendations & Insights Report April 2025

Likes

0

Views

4