The Power of a Story Well Told

How the wizards of Menlo Park and Cupertino re-invented a strategy based on storytelling to finance their products and transform the world

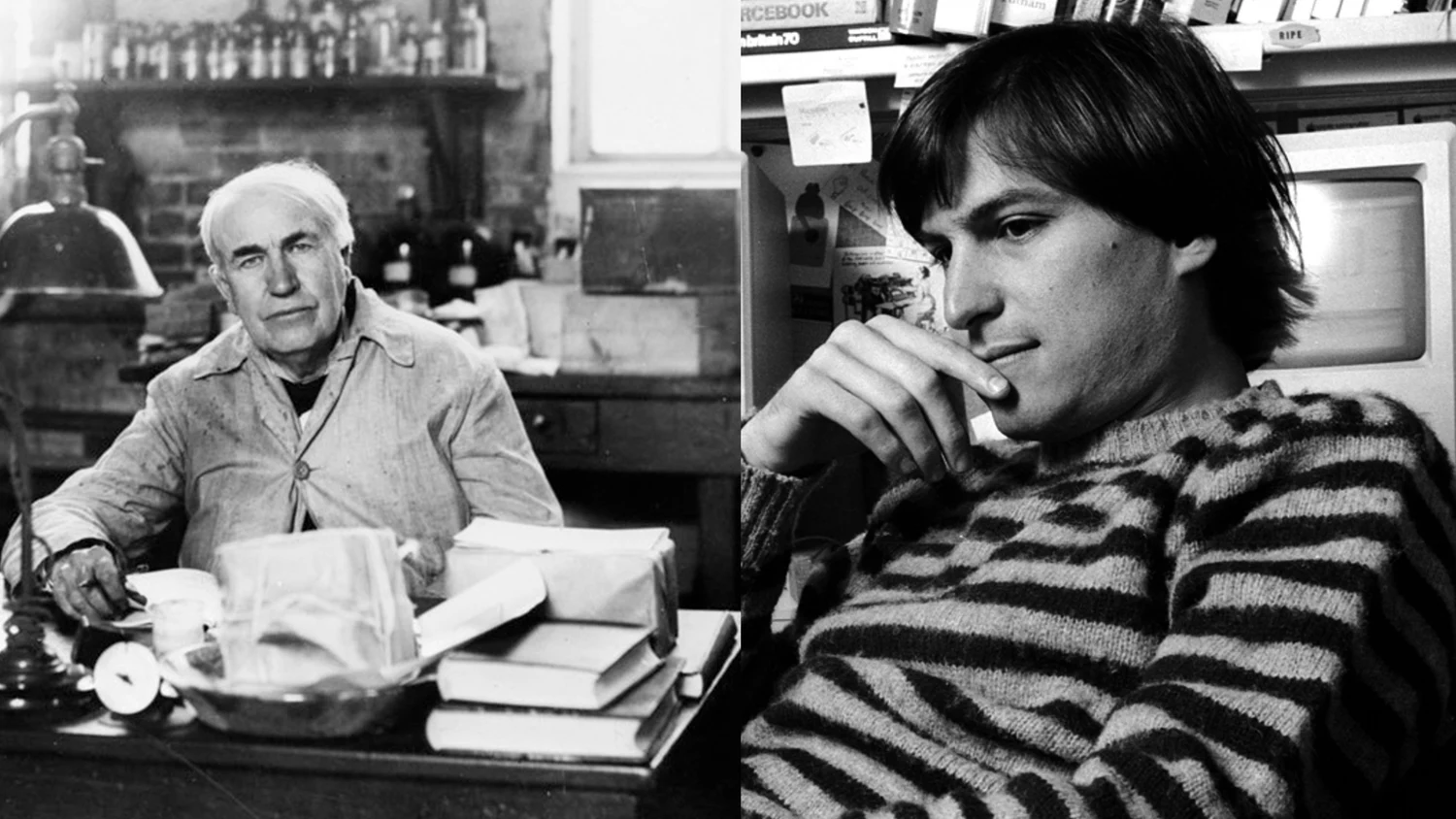

The day Steve Jobs stepped down as the CEO of Apple in 2011, publications from The New Yorker to the Economist chose one specific inventor from the past to compare Jobs’ impact on the course our lives: Thomas Edison.

Like Jobs, Edison’s inventions, may have never seen the light of day without his equally important gift as a creator of a business strategy built on powerfully inspiring stories. Edison, like Jobs after him, understood how the artistic application of a compelling narrative could help him connect with critical audiences to raise critical investment funds and sell to eager consumers.

At his death in 1930, Edison held 1,093 U.S. patents—a record not broken until 2003. His discoveries were so profound, disruptive, and long-lasting they laid the foundations of the wired, high-tech world Jobs helped to create at the end of the last century.

Exactly 100 years before Jobs unveiled the Apple II—the first highly successful personal computer—Edison invented the phonograph. A seemingly magical device in 1877, Edison’s invention took the country by storm. “There were other great inventors” during this period, notes Robert Rosenberg, director for the Thomas Edison Papers. “Then there was Edison.” He understood that inventing is not just having an idea, and so he made Edison a name to be reckoned with.”[iii]

Jobs took the clunky square boxes of early personal computers and transformed them into the Macintosh—a form of art in its own right—both in terms of design and its more intuitive operating system. With the advent of the iPhone, Apple’s vision to merge a portable computer with a cell phone created an invention consumer did not know they needed and revolutionized our lives.

While there were differences between these two icons, the similarities are profound and provide important lessons for future innovators. What truly set Jobs and Edison apart, what magnified their momentum and reach, was their genius in developing a deliberate strategy that combines art with science and the power of transformative storytelling.

Strategic Power and the Art of Storytelling

Edison first learned of the power of a good story at the age of 12 after landing a job as a newspaper boy on a Midwestern railroad. The day after a major Civil War battle broke out, Edison bought extra copies and then telegraphed cities down the line with teaser headlines to tantalize riders before he arrived. He ended up selling a thousand newspapers instead of his usual hundred.[i]

As a professional inventor years later, Edison tirelessly courted fellow scientists, investors, and the media with a carefully planned storytelling strategy. He granted exclusive interviews to favored journalists and offered private sneak-peaks of his latest light bulb before it was ready for production. Typically, he would tell the reporters he had discovered a cheap, reliable, and long-lasting filament. During demonstrations, he flipped the switch, the bulb would light up the room and they would react with cheers of amazement.

The resulting wave of publicity gave Edison a world-wide brand as an inventive genius of wizard-like proportions.

Historian Ernest Freeberg, author of The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America,[ii] says newspaper stories about the inventor captured the imagination of a turn-of-the-century American public eager to believe in the great prodigies of science and industry.

“Edison was himself a great promoter of his image, and it was important to claim to be the sole inventor in order to win the crucial patents that would determine which person got to control the market share,” Freeberg told U.S. News and World Report.[iii] “People wanted to believe in the idea of an inventive genius. Edison certainly was, by any stretch, an inventive genius, but people were very drawn to this idea that Edison was a wizard.”

Better than any of his contemporaries, Edison caught the vision and power of a good business narrative. Innovators like Alexander Graham Bell, Samuel Morse, and Nikola Tesla were all brilliant scientists, but none of them cultivated stories to create an atmosphere of infectious excitement.

— Steve Jobs

Edison’s artistry at storytelling instilled confidence and popularity, attracting big-name financiers like J.P. Morgan who invested in his research center in Menlo Park, N.J. The tales of the “Wizard of Menlo Park” bolstered a new American inventive spirit that lasted for decades. Edison became an icon of technological advancement, a celebrity who ushered America into the modern world.

Whether Jobs studied Edison’s strategy or gleaned it himself, his own flair for the dramatic—from his closely held product launch announcements to the use of strategic narrative to motivate his team of inventors—the Wizard of Cupertino captured the imagination of the public. With an authentic vision for future innovation, he built his own highly successful company that created products that transformed our lives and steered us into the information age.

Jobs asked a small group of employees in 1994 who was the most powerful person in the world. Several responses later, Jobs said they were wrong. “The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values and agenda of an entire generation that is to come.”

Jobs was referring to Walt Disney when he posed the question. The following November, Jobs’ company Pixar released the animated film Toy Story. After its Thanksgiving debut, Toy Story became the highest grossing film of the year, beating Batman Forever and Apollo 13. At the time, it was the third highest grossing animated film in history.

In the summer of 2018, Apple became the first company in history to reach $1 trillion in market capitalization, proving the deliberate merging of art and technology spiced with a healthy dose of storytelling pays lasting dividends.

At Pythia International, we know first-hand that Jobs and Edison created much more than inventions. They discovered a universal principle: storytelling is a powerful force that shapes the world.

Innovation—whether it is a new product, a technological breakthrough, or a novel form of music or art—is essential to progress. But what separates long-lasting commercial successes from abandoned research and development projects is a strategy founded on powerful art of storytelling.

[1] Ken Auletta, “The Wizard of Apple,” The New Yorker (2011). Accessed June 24, 2018

[2] “The Minister of Magic Steps Down, Economist (2011). Accessed June 27, 2018

[3] American Experience, “Edison,” Video (2015; Boston: WGBH/PBS) Transcript. Accessed May 8, 2018

[5] Ernest Freeberg, The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America (Penguin Press, 2013).

[6] Brooke Berger, “Many Minds Produced the Light That Illuminated America,” U.S. News & World Report (2007). Accessed May 7, 2018,

Like this project

Posted Oct 6, 2023

Wrote blog articles on the power of storytelling and other webpage content. The client was very pleased.

Likes

0

Views

11

Clients

Pythia International