Investigative Report: Walter J. Brown Media Archives

Conway SI 678

Investigative Report: Walter J. Brown Media

Archives and Peabody Awards

Executive Summary

The project that I chose to investigate was the Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection, which has over 250,000 audiovisual files and is the third largest broadcasting archives in the world. The Peabody Awards Collection is the main focus of the archives and they contain all the submissions from the annual awards ceremony in New York. The digitization process began in 2007 when the archives were awarded two grants to spur the digitization of its audiovisual materials. One individual used the setup provided by the grant to continue the digitization process on the site moving after the money was used up. It was also here they switched over from using J2K video format to digital video format and later ProRes. In 2012, the BMA expanded their infrastructure to meet the increasing requests for audiovisual materials and in 2015, they also hired their first digital archivist to manage the amount of increasing AV files. A couple years ago, they were awarded another grant to sixty years worth of local public media programs submitted to the Peabody Awards. The process is estimated to last about 18 months, after which they will then be available at the Brown Media Archive and the other centers.

About the project

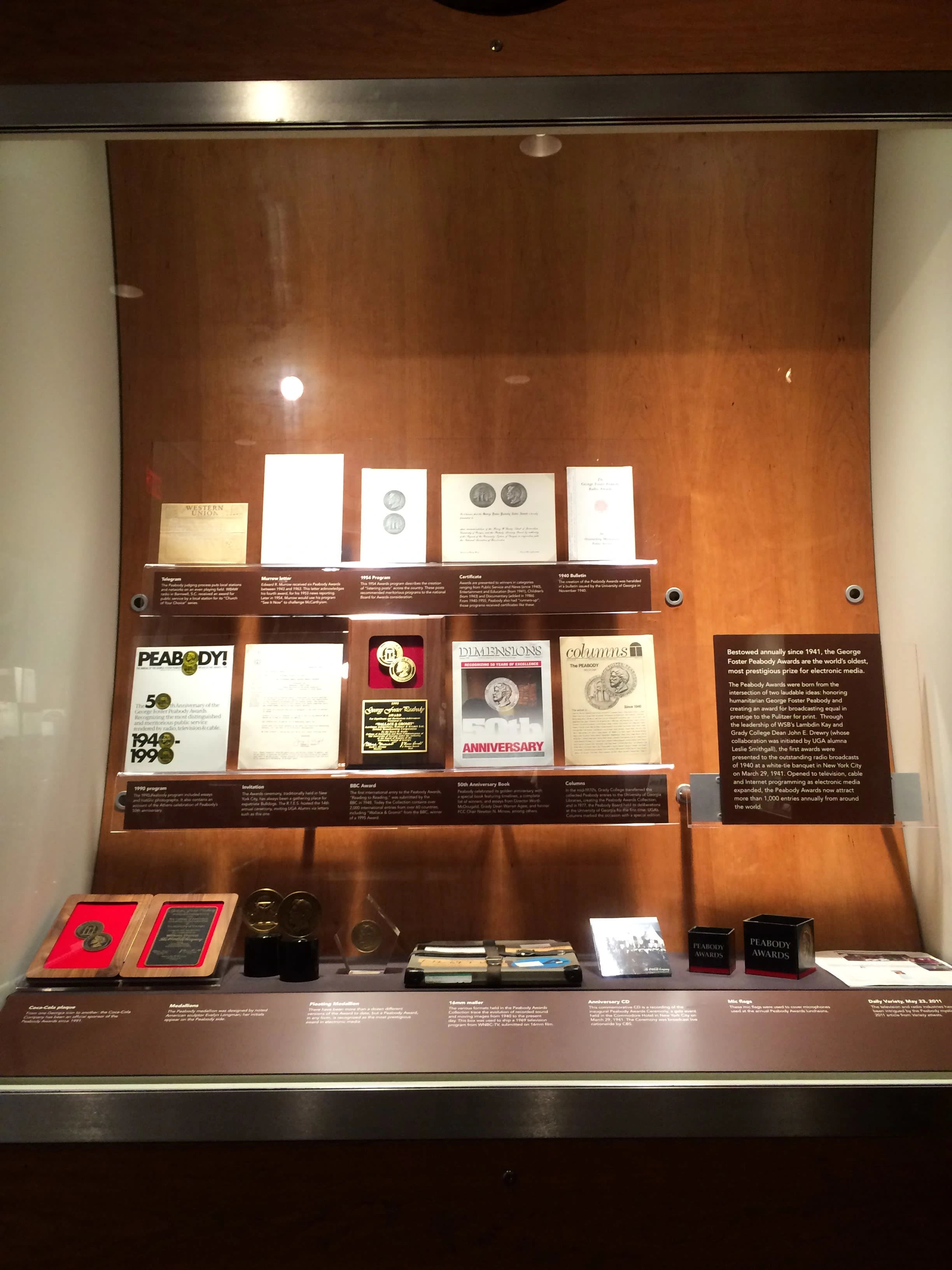

Located at the University of Georgia, the Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection has preserved countless audiovisual files, including VHSs, CDs, and film reels, as well as various audio files, such as audio cassettes, LPs, transcription discs, and audio cartridges. The collection currently has more than 250,000 audiovisual materials preserved, with some materials going back as far as the 1920s. After the Library of Congress and the University of California, Los Angeles, it is the “largest broadcasting archive” (“Walter J. Brown Media Archives”, n.d.) in the United States. According to its official website, the goal of the project is to “preserve and provide access to the moving image and sound materials that reflect the collective memory of broadcasting and the history of the state of Georgia and its people” (“University of Georgia Libraries”, n.d.) The Archives are all part of the Special Collections Library at the University of Georgia, which had recently been moved into a larger building with a better storage environment and more space to accommodate materials into education, as well as galleries to display materials.

The Peabody Awards Collection is the crown jewel, containing more than 90,000 titles, “with radio programs dating from 1940 and television from 1948” (“Walter J. Brown Media Archives”, n.d.). The awards, which are annually held in New York, honor the most influential and exceptional stories in digital media such as television, radio, and the internet. Once the judging is finished and the awards are held, the entries are moved into the main collection in order to be catalogued and preserved. The Peabody Awards Collection brings in at least 1,000 new entries annually, and many of the materials preserved in the collection are the only remaining copies that exist, particularly the initial broadcasts. It is estimated that more than “230 radio and television stations across 46 states are represented in the Peabody collection” (Eversden, 2018).

There are three major news film collections that are specifically focused on the history of Georgia: The WSB Newsfilm Collection, which chronicles the history of Atlanta and the American Southeast from 1949-1981, the WALB Newsfilm Collection, which chronicles the history of the Albany region from 1961-1978, and the WRDW Newsfilm Collection, which chronicles the history from 1961-1976. The Civil Rights Movement is a major focus in each of these collections. It also features collections of miscellaneous audiovisual materials, such as interviews, home movies, and even local-made films.

Although the Archives have been in existence since 1995, it really wasn’t until 2007 that the digitization process really took off. That was the year when the archives were awarded two grants to spur the digitization of its audiovisual materials. According to a presentation done by digital archivist Callie Holmes, the first grant was focused on the materials at the Civil Rights Digital Library, where most of the digitization was done using outside vendors. The second grant was focused on “local television programs from the Peabody Awards Collection” (Holmes, 2018). This grant was especially important, because they could buy SAMMA (System for the Automated Migration of Media Archives) digitization machines which allowed them to create MXF-wrapped J2K files, which are some of the most important files for video preservation. During these grants, there was one individual, who had a background in video production and used the outline from the grant to keep the digitization process in-house moving after the money was used up. He led the digitization process based on the business’s “current trends” (Holmes, 2018). Among other things, he also found issues using J2K video format and shifted to digital video format and later ProRes.

By 2012, more requests for audiovisual materials were coming in, not just from students and individual researchers, but also from various production companies. In order to meet that demand, the BMA expanded their infrastructure and “automated processes” (Holmes, 2018) through programming. However, as more and more digital files were created, the University of Georgia recognized the need to have a more universal approach to manage all of them. In 2015, they hired their first digital archivist to address this need. The Archives also obtained a film scanner, which allowed them to create tons of DPX files. With so many of them, it required an increase in storage and a better system to manage analog and digital collections. A new content management system called Collective Access was introduced to address this problem. However, Alex couldn’t completely get Collective Access set up during his time, and it still hasn’t been completed.

Less than two years ago, another grant was awarded to the BMA to fund to “preserve an estimated 4,000 hours of local public media programs submitted to the Peabody Awards” (Eversden, 2018) over a period of sixty years. The archivists there are working together with the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, which in turn is a “collaboration between Boston’s WGBH Educational Foundation and the Library of Congress” (Eversden, 2018). According to a news article regarding the project, one of the programs being preserved is a radio documentary about Woody Guthrie that was very well known at the time it was aired in 1999 but has now been largely forgotten about. Therefore, preserving it ensures that people will remember when it was made. Furthermore, since many of the materials will deteriorate overtime, preservation ensures they will stay around forever. Most of the money for the grant will be used to “pay for a vendor to digitize the programming” (Eversden, 2018) and the digitization process is estimated to last about 18 months. These programs will then be available at the Brown Media Archive and the other centers.

Investigative Process

As part of my investigative process to go into what the Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards are all about and what they are currently doing, I went onto the official website for the collections as well as related sites from the University of Georgia.

I also browsed around through the internet to see if I could find any news articles related to what they are doing and it was here that I discovered the grant being awarded two years ago to help them preserve a large amount of the collection.

To learn more about the process behind digitization procedure, I got in contact with Callie Holmes, who is a digital archivist at the Brown Media Archives/Peabody Awards and learned more about the process behind digital preservation, some of the standards they use, and whether or not they use outside vendors.

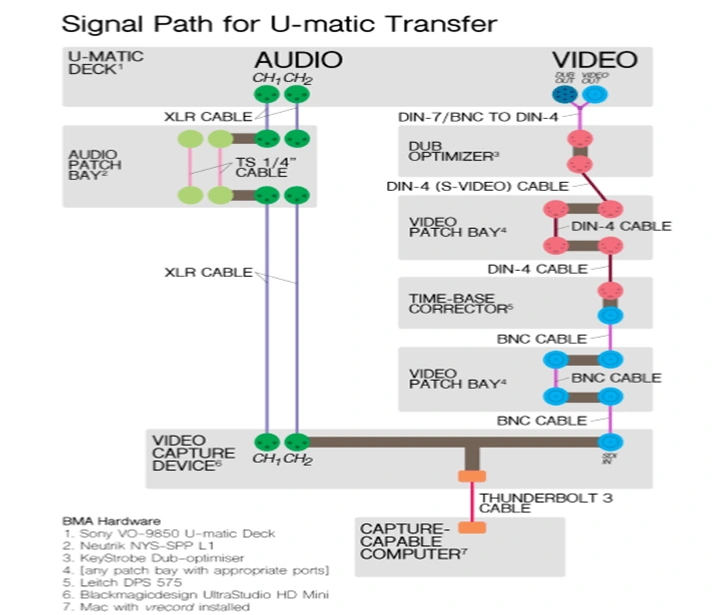

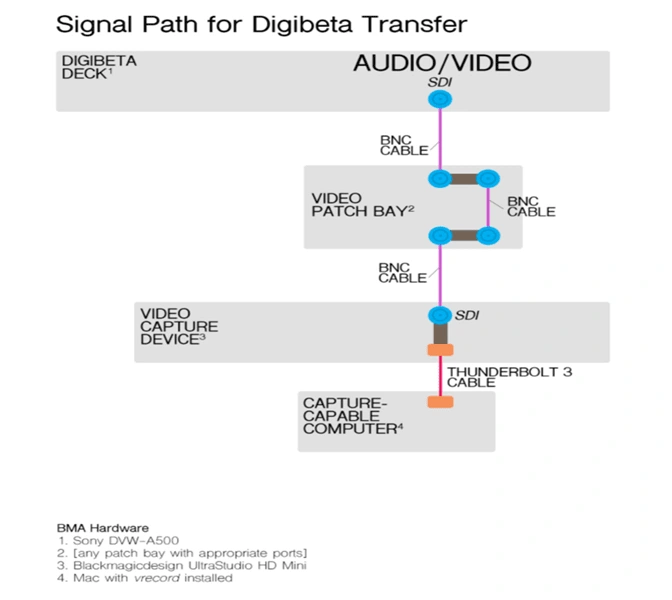

As part of the interview, she gave me several diagrams showing the signal paths for various formats and their digitization and access workflows.

I also obtained a PowerPoint of a lecture that she did regarding the background for digitization at the Brown Media Archives, and their future plans to digitize the collection.

The process behind preservation

The process for digitizing a file occurs mostly upon request; people can search through the collections through their online catalogs and request a file, which will be digitized along a few other key items., and the proxy file put online for the researcher to review. According to the interview I held, while the staff do take note of format risk and obsolescence, they are not holistically looking at the collections and digitizing based on that. There is hardly an instance in which someone needs to extract the original analog item. Some of the standards that are used for digitization are designed to create an outline for setting up a new signal path. It’s not so much a given set of instructions, but more like a series of recommendations. The digital preservation format that they use for video is MP3 coded Matroska files, and during the process, they need to look at certain levels. For audio, the preservation format is wav. file. They capture a video signal or audio signal that is losslessly compressed.

While the archives mostly digitize the files themselves, they also use outside vendors for different projects. The archives currently must digitize about 4000 items in the Peabody Awards Collection and that’s not feasible to do all of that within the main facility. If there is a request of a volume that they can’t meet, they will use a vendor. Such instances could include when the film requested is one they don’t have the resources or experience for quickly digitizing, such as 35 mm, or if they have collections that have some degree of deterioration, since those collections would require special cleaning equipment. The archives also occasionally get film prints made, which don’t just preserve digitally. Since it’s less likely that they use a film print page for preservation, they will also go for outside help. There are also instances in which it’s just easier to send off a file to a vendor because there’s a budget lined up for preservation, so they try that for digital preservation and reformatting. Unless they decide to buy new equipment, that money will be used on vendors. Some of the vendors that were specifically mentioned were Iron Mountain, ColorLab, Preserve South, George Blood, among others.

Iron Mountain has a digital archive management system known as the Digital Content Repository (DCR), which was developed by the “media and archive professionals” (“Digital Content Repository”, n.d.) exclusively for those in the field. It features the “latest technology” and organizational innovations and enables clients to take in and oversee assets with regulated “access across a team or company” (“Digital Content Repository”, n.d.), while at the same time, letting them “have access and visibility across an entire archive” (“Digital Content Repository”, n.d.). ColorLab deals almost exclusively with motion picture film and is one of the most highly regarded vendors in audiovisual preservation. Preserve South, which “[specializes] in digitization and media migration” (“Our Scanner has Arrived”, 2018), has recently obtained a new ScanStation designed to create film scans in full 5K resolution. George Blood was probably one of the very first pioneers in the field of preserving archived audio and video. Aside from “[migrating and translating data] from early tape and disc formats”, Blood also has the necessary equipment to clean up and “digitize obsolete and deteriorating” audiovisual material (“George Blood”, n.d.).

Digitization specs

The following diagrams showcase the signal paths for some of the formats used by the digitization of the Brown Media Archives:

As is seen in this diagram, the U-matic transfer system separates different AM and FM signals, known as chroma and luma, and “reduces the chroma for recording” (“TC-06 Guidelines”, 2019). In order to reduce the playback errors, the signal from the VTR is calibrated using the various settings on the VTR.

Any digitization system should include always have some form of quality control so that the transfer of the video collections is accurate and nothing is lost. Based on the readings for the IASA guidelines, U-matic has a slower rate of speed for the tape and there is “less space reserved for audio tracks” (“TC-06 Guidelines”, 2019). This ends up with a lower sound quality and is therefore not ideal for IASA guidelines.

As this diagram indicates, there are five audio channels used by DigiBeta: four digital channels, “all of them recorded at 48kHz and 20 bits per sample” (“TC-06 Guidelines”, 2019), and one analogue cue track. Since there is a much lower risk of the AV recordings being altered or some of data being lost, digital betacam is often considered a better choice for preservation based on the IASA guidelines.

Reflections

During my time in this course, I learned a great deal about the ethics for the proper preservation of sound and motion, as well as some of the most important procedures for their digitization. Whenever you digitize audio and visual recordings, you want to make sure that you are extracting the original recordings as accurately as possible and avoid practices in which the quality of the digital recording could be diminished. After investigating the Peabody Awards Collection and the Brown Media Archives, I found myself to be quite impressed by their dedication to the recommended practices of preserving sound and motion, and I am really looking forward to hearing more news about the future of this project.

Sources

Holmes, C. (2018, October 26). Open Media @ UGA [Lecture notes or PowerPoint slides].

Digital Content Repository. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ironmountain.com/industries/entertainment/digital-content-repository.

Eversden, A. (2018, August 3). UGA project will preserve decades of local pubmedia programs entered in Peabody Awards. Retrieved from https://current.org/2018/08/uga-project-will-preserve-decades-of-local-pubmedia-programs-entered-in-peabody-awards/.

George Blood. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.georgeblood.com/.

Our film scanner has arrived! (2018, March 13). Retrieved from https://www.preservesouth.com/our-film-scanner-has-arrived/

PEABODY AWARDS COLLECTION. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://bmac.libs.uga.edu/pawtucket2/index.php/Peabody/Index.

TC 06 Guidelines for the Preservation of Video Recordings. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.iasa-web.org/tc06/guidelines-preservation-video-recordings.

University of Georgia Libraries. (n.d.). The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection. Retrieved from https://www.libs.uga.edu/development/naming/brown.

Walter J. Brown Media Archives. (n.d.). About. Retrieved from https://bmac.libs.uga.edu/pawtucket2/index.php/About/Index.

Like this project

Posted Mar 21, 2025

Researched preservation practices at the Peabody Awards Collection, analyzing digitization workflows and archival strategies for audiovisual media.

Likes

0

Views

7

Timeline

Sep 1, 2019 - Nov 30, 2019

Clients

University of Michigan School of Information