Masters Thesis

Like this project

Posted Apr 24, 2024

Investigated and researched the links between redlining, policing, and food access in Philadelphia neighborhoods.

Likes

0

Views

17

Disinvesting in Food: How Philadelphia’s History of Redlining and Food Apartheid has Contributed to Mass Incarceration

A Thesis

Submitted to the Faculty

of

Drexel University

by

Farwa Zaidi

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree

of

Master of Science in Urban Strategy

June 2023

© Copyright 2023

Farwa Zaidi. All Rights Reserved.

ii

Dedications

To all the women who have always encouraged me to value my intelligence and

education: I am because you are.

iii

Acknowledgements

It takes a village, and I am so grateful for mine.

A million thanks to all of my professors at Drexel who have planted so many

seeds in me and have been so supportive, helpful, and caring. None of this would have

been possible without the help and support of my program director Andrew Zitcer, who

has been in my corner since before I even applied to Drexel. Thank you, Andrew, for

always believing in me and providing this space for me to learn and grow. To my thesis

advisor, Clara Pinsky, thank you for helping me see my potential and path with this

topic. This thesis was a team effort between the two of us, and you deserve as much

credit as I do.

To all the research subjects who took time out of their days and schedules to

speak to me and take such an active interest in my project, thank you for educating me

with your perspectives and insights.

To my family and friends, who have showered me with well wishes, support, love,

and care throughout the graduate school process- I never could have done any of this

on my own. To my Urban Strategy cohort who I’ve spent the past two years with, I am

so grateful to have shared this experience with you all and to have been able to witness

your wisdom and intelligence. I appreciate you all so much.

And lastly, to my husband Abbas- you see me even when I can’t see myself. I

could never have started on this path without you. Thank you.

iv

Table of Contents

List of Tables v

List of Figures vi

Abstract vii

Chapter 1: Introduction 1

Preface 1

Purpose and Problem Statement 2

Research Methods and Protocols 4

Expected Findings 5

Limitations 5

Chapter 2: Literature Review 7

Introduction 7

Food Apartheid, Food Swamps, and Corner Stores 8

Redlining and Disinvestment 10

Incarceration and Food Access 14

Food Access, Incarceration, and Health 15

Food Sovereignty and Food Justice 19

Urban Gardening and Agriculture 23

Conclusion 25

Chapter 3: Planning Discrimination: How Redlining Shaped Food Apartheid in Philadelphia 26

Redlining and Food 26

Food Apartheid + Food Swamps 29

Access to Resources 33

Gentrification 36

Urban Gardening and Agriculture 39

Chapter 4: How Food Access Determines Police Presence 42

Introduction 42

Criminalization of Corner Stores 42

Police Activity 45

SNAP and Food Stamps 48

Chapter 5: Recommendations 51

Chapter 6: Conclusion 59

Works Cited 60

Appendices 71

Appendix A 71

v

List of Tables

Table 1. Recommended Action Areas and Strategies to Reverse the Impact of Historic

Redlining. 51

vi

List of Figures

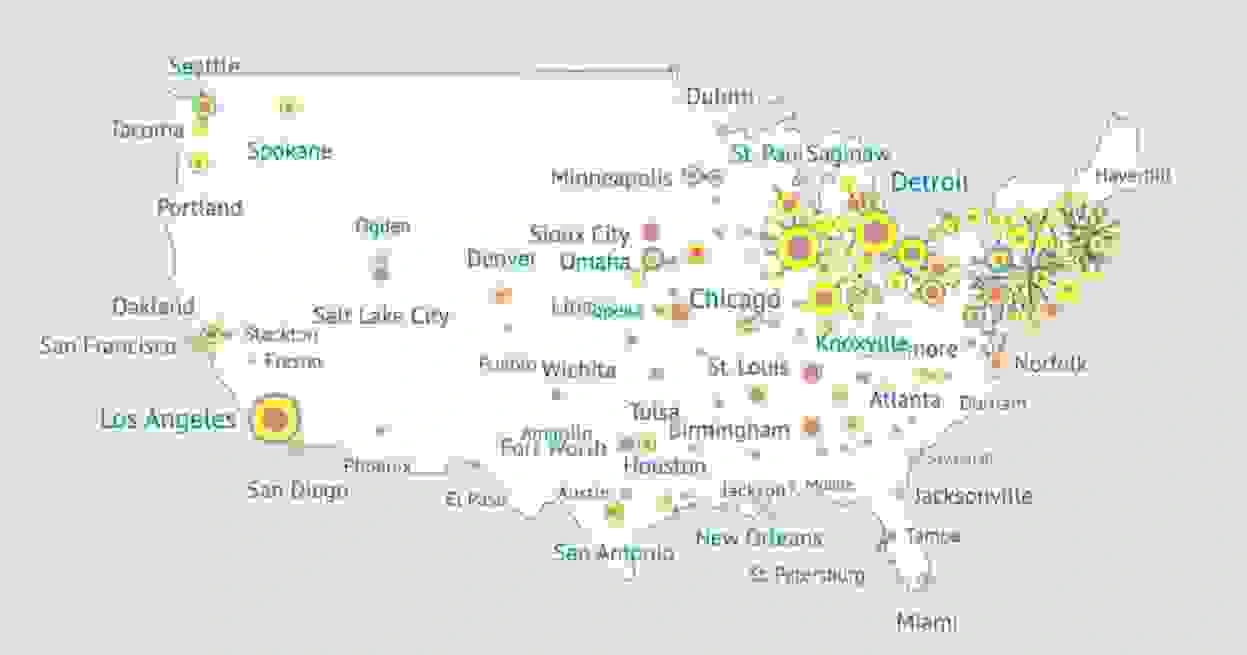

Figure 1. Redlining across the United States 11

Figure 2. Violent crime rates in redlined neighborhoods. 13

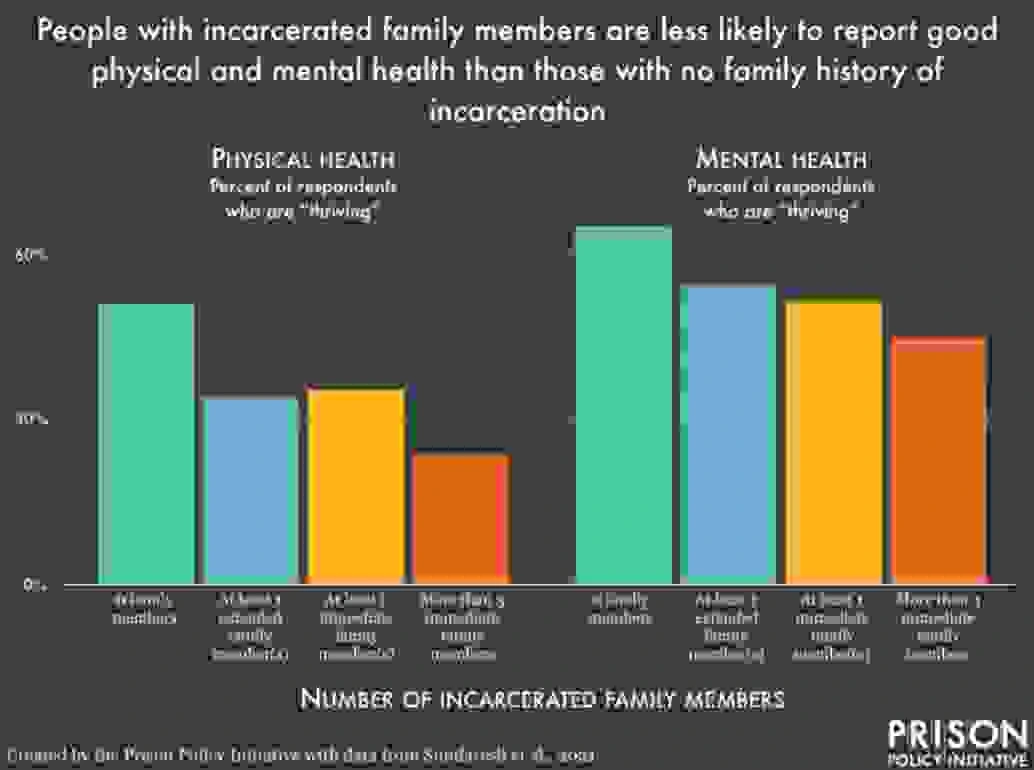

Figure 3. The Physical and Mental Health of People with Incarcerated Family Members. 17

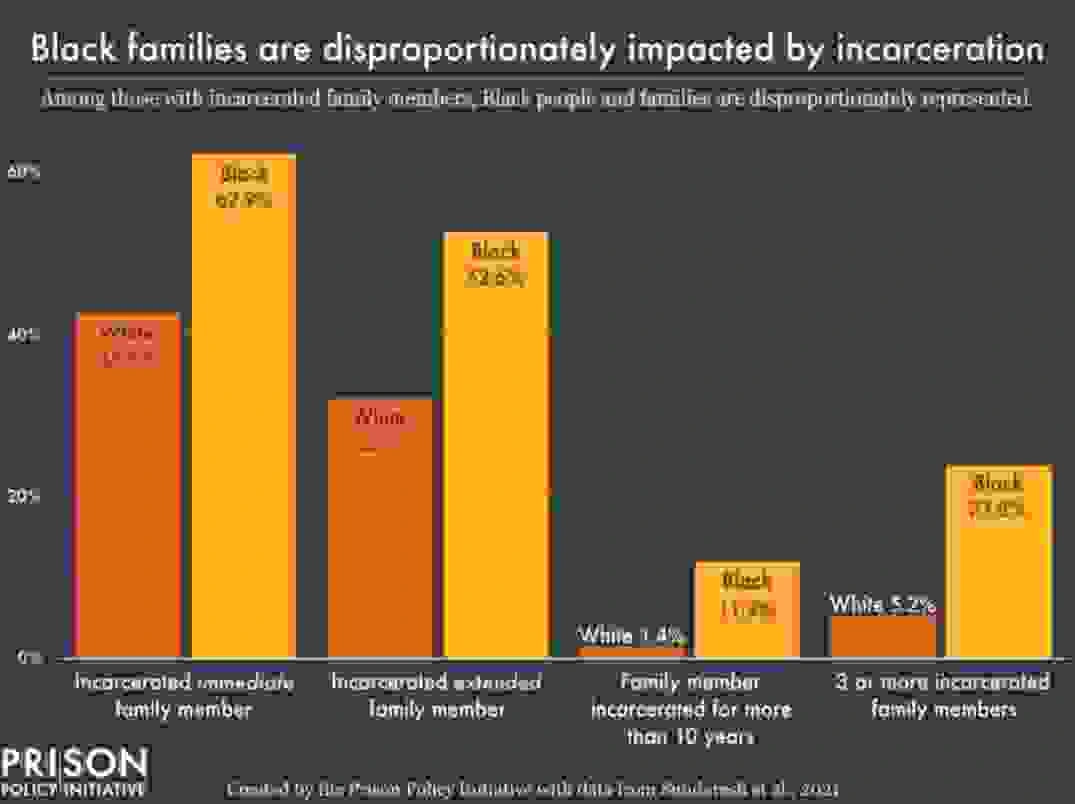

Figure 4. Rates of Incarcerated Family Members by Race. 18

Figure 5. The Six Pillars of Food Sovereignty. 22

Figure 6. A Redlining Map of Philadelphia. 26

Figure 7. Philadelphia Food Retailers. 30

Figure 8. Number of Low-Produce Supply Stores, Philadelphia. 31

Figure 9. Police Stops and Gentrification from 2014 to 2019. 37

Figure 10. A corner store threatening police action in West Philadelphia. 43

Figure 11. The rate of pedestrian stop-and-frisk incidents in Philadelphia between 2014 and

2015. 45

Figure 12. The City of Minneapolis Action Steps to Establish Equitable Distribution of Food

Sources and Food Markets for all Residents by 2040. 53

vii

Abstract

Disinvesting in Food: How Philadelphia’s History of Redlining and Food Apartheid has

Contributed to Mass Incarceration

Farwa Zaidi

Advisor: Clara Pinsky

Philadelphia has a long and tragic history of redlining and disinvestment, impacting

African American residents at disproportionate rates. Neighborhoods where African Americans

and other communities of color have lived have lost opportunities to green spaces, clean air,

quality education, and healthy food retailers. Redlining and disinvestment can also lead to higher

rates of crime, violence, and policing. The relationship between redlining, food access, and

incarceration shows the way marginalized groups have been targeted by unjust policing and

unhealthy circumstances.

This thesis examines the relationship between redlining, food access, and incarceration in

Philadelphia neighborhoods. By speaking with field experts in food access, food justice, and the

carceral justice system, I present a case study of Philadelphia and how decades of disinvestment

have led to neighborhoods with low access to quality healthy foods and high rates of pedestrian

stop and frisk incidents, gentrification, and policing. I then offer four recommendations for

policymakers nationwide to end disinvestment and increase food access: reduce poverty, create

accessible and affordable food production, address the impacts of climate change on food, and

reverse the links between food, policing, and incarceration.

1

Chapter 1: Introduction Preface

In the public health sphere, experts and students alike recognize the various elements of a

truly healthy society include access to resources such as green spaces, clean air and water,

healthcare, economic opportunities, and healthy food. It is impossible to improve just one

element while ignoring others and expect public health challenges to cease. In Philadelphia,

Black and brown residents face multiple levels of inequality that contributes to their poor health

including dangerous levels of heat in the summers, polluted air from living near refineries, and

lack of access to healthy foods.

The process of redlining Philadelphia neighborhoods in the 1930s—marking

neighborhoods where poor, Black and immigrant residents lived as hazardous and ineligible for

mortgages and credit—has contributed to many of the risk factors for poor health that Black

Philadelphians now live under. Philadelphia neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s are

now at higher risk for gun violence, food apartheid, and more.

In my years living in Philadelphia, I have observed just how scarce healthy food can be in

neighborhoods, many that were previously redlined. In addition, I began to wonder if this lack of

healthy food was connected to other factors of violence in the city. Police brutality and

incarceration are also risk factors for health (Alang and McCreedy, 2021) - are they too

connected?

The current criminal justice system in the United States is a remnant of slavery and the

plantation system; it was created in large part to target and criminalize Black and brown

communities. The first formation of policing was found in slave patrols and night watches whose

2

job it was to capture runaway slaves.1 Police brutality is an extension of this criminalization and

violence. As a police and prisons abolitionist, I believe in a transformative worldview: that we

can and should work to create a healthier and more just society for all people that will contribute

to the destruction of police and prisons. Dr. Ashante Reese writes that “A contemporary

abolitionist practice must create the conditions for healthy communities. To that end, the work of

nourishing people and building just food systems is necessary” (Reese, 2020). My thesis aims to

contribute to a healthy society by researching how food access in formerly redlined

neighborhoods plays a role in carcerality and criminalization, and how we can work to reverse

that. My intention is to see if improving access to healthy foods can contribute to the abolitionist

movement, to create more just and equitable societies for Black and brown people- particularly

in Philadelphia.

Purpose and Problem Statement My guiding research questions are: Is there a relationship between food access, or food

scarcity in formerly redlined neighborhoods, and the carceral justice system? Do people who live

in areas of food apartheid2 have a higher likelihood of being targeted by police, or being part of

the criminal justice system? What is the relationship between healthy food access and

disproportionate policing?

The purpose of my thesis is to understand the relationship between food insecurity and the

criminal justice system, particularly in Philadelphia’s previously redlined neighborhoods. I want

to explore if the availability of healthy food that has been systematically withheld from redlined

neighborhoods has an impact on the dynamic with the carceral justice system. Exploring this link

1E. Kappeler, Victor. 2014. “A Brief History of Slavery and the Origins of American Policing.” EKU Online (blog). January 7, 2014.

https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/brief-history-slavery-and-origins-american-policing/.

2Food apartheid has replaced the term ‘food desert’ in recent years, and is defined as areas empty of good-quality, affordable fresh food

(Brones, 2018).

3

can help us begin to break down systems that disproportionately incarcerate Black and brown

communities and deny them healthy foods.

My research questions are important because the results may prove that areas of food

apartheid and redlining are connected to crime and policing. A plethora of research has found

that food apartheid areas and formerly redlined neighborhoods have a direct link to health

deficits and are already a public health issue. Learning that they may also be a contributing factor

to high levels of crime and unjust policing would further prove that food apartheid must be

addressed in order to abolish prisons and that neighborhoods that were redlined in the past

should be provided with resources equal to their non-redlined counterparts.

These questions are important to the field of urban strategy because the answers might

prove that cities must invest more time, money, and energy into making healthy foods available

in all neighborhoods. The data could also show that there is a disproportionate rate of policing in

food apartheid areas, while the resources used for said policing could instead be implemented in

providing healthy foods.

Existing literature that I explored relative to my topic are articles and books that focus

primarily on incarceration, abolition, and food. Many articles explore the relationship between

food scarcity and the carceral justice system. Others explore the role of community and urban

gardens in feeding impoverished neighborhoods. Some examine the role that agriculture and the

current day plantation play in the disproportionate incarceration of Black Americans.

My research methods included gathering data and information from existing literature

and from conducting interviews with experts in the field. These experts included professors who

have researched food scarcity, Philadelphians who are working to provide healthy food to all

residents, and authors who have written on the topics. I believe these are appropriate because

4

they all provided data and research as it pertains to my research questions. They also informed

whether these links have been observed in the past, by who, and where.

Research Methods and Protocols My thesis examines and evaluates whether there is a link between food insecurity and the

carceral justice system. My qualitative research consisted of interviewing and conversing with

experts in the field who have done similar research.

My research subjects are as follows:

● Mariana Chilton, Director of the Dornsife School’s Center for Hunger Free

Communities.

● Joshua Sbicca, food justice expert and author of Food Justice Now.

● Nyssa Entrekin, Associate Director of the Healthy Corner Store Initiative at The

Food Trust

● Wayne Williams, Program Manager of Community Based Programming at The

Food Trust

● Janice Tosto, Hunger Relief Supervisor at Bebashi

● Ashley Gripper, Founder of Land Based Jawns

● Katherine Alaimo, Associate Professor, Director, Sustainable Agriculture and

Food Systems Minor and Specialization at Michigan State University

● Matt Stebins and Kaelee Shepherd, Community organizers for the Coral Street

Fridge

● Sonia Parikh, Co-Founder of The People’s Fridge

● Nicholas Freudenberg, Senior Faculty Fellow at the CUNY Urban Food Policy

Institute

5

● Ashley Gurvitz, CEO at The Alliance for Northeast Unification

● Alison Alkon, Co-editor of Cultivating Food Justice

● Kanav Kathuria, Founder of the Maryland Food and Prison Abolition Project

All my subjects received the proper IRB form, as well as being notified that our

conversations were recorded. Since they are experts in their fields, I used their real names-

however I protected the confidentiality of anyone they talk about. Since this research focuses

heavily on people who are targeted by the carceral justice system, I feel strongly that their names

should be protected.

The interview questions that guided my conversations with my research subjects can be

found in Appendix A.

Expected Findings I hypothesize that I will find a link between food scarcity and the carceral justice system.

If not a correlation or causation, a relationship. According to research I have already done, food

insecurity can lead to increased crime and violence rates. I predict that as a person’s relationship

(and access) to healthy food changes, so too does their relationship to the justice system,

redlining, and poverty.

Limitations My limitations in the paper are that I will only be focusing on Philadelphia, because my

goal is to propose policies that will help the city I know best. I will not be able to speak to

formerly, or currently, incarcerated people, due to the sensitive nature of seeking them out. I

believe my research would be bettered by learning firsthand the relationship that formerly

incarcerated people have with food, but I have few ways of achieving that. I cannot research

neighborhoods with high rates of formerly incarcerated residents, due to a lack of data. There is

also limited data on policing rates in neighborhoods of food apartheid and food swamps. There is

6

a plethora of data on where crimes occur most, but none on where police target residents the

most- regardless of whether or not crimes are committed. Additionally, I am limited in

suggesting that there is a causal link between food access and incarceration rates. While a

person’s relationship to food might impact their relationship to the carceral justice system, it will

be difficult to prove that there is a direct causation between the two.

7

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Introduction For abolitionists, the end of police and prisons is an overarching goal to achieve freedom.

However, many experts and activists recognize that abolishing these systems will not occur in a

vacuum. In the United States, policing and prisons were created to criminalize Black and brown

communities, as just one of the ways they experience everyday violence at the hands of the state.

Many experts and historians have argued that policing and prisons are simply an extension of the

slave state. Kica Matos and Jamila Hodge write that:

Because the 13th Amendment3 exempted people convicted of crimes, the criminal legal

system has been used to extract labor from enslaved people’s descendants. Immediately

after the abolition of slavery, Black codes4 criminalized activities like selling crops

without permission from a white person. Other laws criminalized Black people for being

too close to a white person in public, walking “without purpose,” walking next to railroad

tracks, or assembling after dark (2021).

Slavery’s lasting legacy can be found in today’s police and prison forces because policing and

prisons were first created in the United States to uphold slavery. Further examples of systemic

violence against Black and brown people can be found in the built environment5, gentrification6,

redlining, and more. All of these violent policies and practices are couched and rooted in racism.

A lack of access to healthy foods is one such example of this violence. Food access, or

lack thereof, lives at the intersection of the built environment, redlining, gentrification, and

3The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for

crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction" (National Archives, 2022).

4After the Civil War ended in 1865, some states passed black codes that severely limited the rights of Black people, many of whom had been

enslaved. (National Geographic, 2022)

5 The built environment can generally be described as the man-made or modified structures that provide people with living, working, and

recreational spaces. (EPA, 2022) 6Gentrification is a process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild

homes and businesses and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents. (Merriam Webster)

8

policing. My thesis will demonstrate these dynamics in action. Ashante Reese, an expert in the

field of food justice, food sovereignty, and racism in the food systems, writes that: “Abolitionist

theory…makes connections between how power that is concentrated in police forces and prisons

flows into other parts of our lives through channels such as the food system” (Reese, 2020).

In the rest of this literature review, I will focus on topics such as food apartheid and food

swamps, and the role that corner stores play in healthy food access. I will explain the history of

redlining and how it has shaped the environments that Black and poor people live in. I will also

explore the links between incarceration and the food system and describe the food justice and

food sovereignty movements and their roles in food access. Lastly, I will discuss urban gardening

and agriculture, and how they increase access to healthy foods while also providing at-risk youth

with opportunities that help them avoid the criminal justice system. I will describe these and

more in this review of contemporary and foundational literature.

Food Apartheid, Food Swamps, and Corner Stores Food apartheid, otherwise known as food deserts, describes a neighborhood or area that

does not have any good quality or affordable fresh food retailers. The term ‘food desert’ was first

introduced in 1995, in a British report on malnutrition. It was first used to describe a public

housing development whose residents had poor access to nutritious foods (Rogers, 2023). A few

years later, when it gained prominence in the United States, it became widely understood as a

primary reason for high diabetes and obesity rates (Kolb, 2022, 1). The concept became so

popular, in fact, that it grew from a fledgling idea to a source for major federal programs within

just two decades (Kolb, 2022, 1). By 2014, the term food desert was mostly often applied urban

areas with high percentages of Black residents, particularly in Detroit and Philadelphia (Kolb,

2022, 6).

9

In recent years, food activist Karen Washington coined the term food apartheid, to replace

food desert. She argues that while deserts are natural and organic, food deserts are not. They are

a direct result of the racist food system in the US (Lakhani, 2021). For the purposes of this paper,

I will be using the term food apartheid as opposed to food desert, because I too believe that the

system of food distribution is intentionally and systematically prejudiced.

In recent years, numerous policies have been drafted and proposed in an effort to

‘eliminate’ food apartheid. For example, in February of 2021, U.S. Senator Mark R. Warner (D-

VA), along with Senators Jerry Moran (R-KS), Bob Casey (D-PA), and Shelley Moore Capito

(R-WV), introduced the Healthy Food Access for All Americans (HFAAA) Act. The legislation

aimed to expand access to affordable and nutritious food in areas designated as food apartheid

areas (Warner, 2021). As of June 2023, the act has not passed.

There is prior research on crimes and food apartheid areas; one report claims that every

one percent increase in food insecurity leads to an approximately 12 percent increase in violent

crime (Caughron, 2016). There is also a plethora of research on disadvantaged communities and

incarceration. For example, one report claims that asthma rates were higher in New York City

neighborhoods with higher incarceration rates (Gifford, 2019). I aim to explore whether or not

neighborhoods with a lack of food access also have higher incarceration rates. There is already

vast research on the health impacts of neighborhood food access, such as cardiovascular health

and diet related diseases.

Relevant to food apartheid neighborhoods are also food swamp neighborhoods. Food

swamps describe an area where corner stores with unhealthy food items and fast-food

establishments are more prevalent than stores that provide healthy foods (CDC). Research in the

U.S found that food swamps actually have a higher impact on obesity and diabetes rates than

10

food apartheid areas (Daghigh, 2019). Research has found that low-income and minority

populations are far likelier to live in food swamps than their white counterparts, and it has

adverse effects on their health (Cooksey-Stowers et al., 2017). In fact, a report found that fast

food restaurants are more likely to open in neighborhoods with high concentrations of non-white

residents. This proves the relationship between race, class, and food environments, with one

report stating that “These associations raise questions about causality and suggest that the race

and ethnicity of a community shapes the actions of the food industry and community design

decision makers, which in turn, influence the food environment” (Cooksey-Stowers et al., 2017).

Redlining and Disinvestment The term "redlining" comes from the development by the federal government of maps of

every metropolitan area in the country during the New Deal. Those maps were color-coded by

first the Home Owners Loan Corp., then the Federal Housing Administration, then adopted by

the Veterans Administration, and these color codes were designed to indicate where it was “safe”

to insure mortgages. Anywhere where African Americans lived, anywhere where African

Americans lived nearby, were colored red to indicate to appraisers that these neighborhoods were

too risky to insure mortgages (Gross, 2017).

African American residents in red colored areas were rejected for mortgages and credit

from banks. Over time, their neighborhoods became the most disinvested in (Blumgart, 2017).

Redlining is how segregation has been built into our neighborhoods and cities intentionally. The

Color of Law, a seminal book on the topic, states that

Today’s racial segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended

consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but

of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United

States. [Redlining] was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present

time (Rothstein, 2017).

11

The Homeowners’ Loan Corporation mapped over two-hundred cities across the United States

(Adkins, 2021). Poor, immigrant, and Black communities were the most heavily impacted by the

system. Across the US, neighborhoods with large swaths of African American residents saw their

communities lose access to resources and mortgage lending that went instead to their white

counterparts. As seen in Figure 1, many Northeastern states where African Americans had

escaped to post-slavery were the most heavily redlined.

Figure 1. Redlining across the United States Source: Adkins, 2021

Redlining and segregation have also played a role in the current system of mass

incarceration in the United States. The long-term disinvestment in schools and education led to

high dropout rates and less job opportunities in Black neighborhoods, incentivizing crime for

many Black men (Waterman, 2016). Additionally, the infamous War on Drugs in the US in the

1980’s intentionally targeted poor Black Americans in low-income, inner-city neighborhoods.

12

Many of these neighborhoods had a previous history of redlining (Wingfield, 2022). This

intersection of drugs, incarceration, and poverty has had a lasting impact on African American

communities:

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and 1988 established mandatory minimum sentences

which largely targeted communities of color. Five-year mandatory minimums were

placed for first-time possession of five grams of crack cocaine, compared to a five-year

mandatory minimum for first-time possession of five hundred grams of powder cocaine.

Crack cocaine was more common in low-income, inner-city neighborhoods, often

communities of color, whereas powder cocaine was more expensive and associated with

whites. As a result of these disparities in sentencing for crack versus powder cocaine, the

criminal justice system was racialized. A link was made between the Black community,

drugs, and crime that would be cemented in American rhetoric, policy, and systems of

law enforcement for years to come (Wingfield, 2022).

Residents of historically redlined areas are subject to increased rates of gunshot-related ED visits

and injuries, increased odds of preterm birth, and higher rates of diabetes specific mortality and

years of life lost (Egede et al., 2023). Redlined neighborhoods also have higher rates of violent

crime, as shown in Figure 2.

13

Figure 2. Violent crime rates in redlined neighborhoods. Source: Townsley et al., 2021

Redlining and food apartheid are linked in a phenomenon called supermarket redlining.

Supermarket redlining is when major chain supermarkets are disinclined to locate their stores in

inner cities or low-income neighborhoods and usually pull their existing stores out and relocate

them to suburbs (Zhang and Debarchana, 2015). In the 1990s, many supermarkets fled urban

neighborhoods in a process similar to White Flight7. Urban planner Julian Agyeman writes that

There is a cultural bias among large retailers against putting outlets in minority-populated

areas. Speaking about why supermarkets were fleeing the New York borough of Queens

in the 1990s, the city’s then-Consumer Affairs Commissioner Mark Green put it this way:

“First they may fear that they do not understand the minority market. But second is their

knee-jerk premise that Blacks are poor, and poor people are a poor market” (Agyeman,

2021).

7A term that originated in the United States, starting in the mid-20th century, and applied to the large-scale migration of people of various

European ancestries from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions.

14

It is important to remember that these communities were made poor intentionally by redlining

and the disinvestment that followed. The wealth gap was created by redlining.

Another result of decades long redlining and disinvestment is gentrification. Redlining

has devalued real estate in inner cities so much that it has now become profitable for investors to

come in and start making money by purchasing properties at low cost, tearing them down and

building higher priced homes (World Food Policy Center). After decades of disinvestment that

resulted in poor food access, education quality, and greenery, gentrification shows that when

neighborhoods are populated with low-income Black and brown residents, they are perceived as

not worth investing in. Only once white middle class residents move in does investment flow.

Incarceration and Food Access Prisons and policing have roots in slavery and plantation ideology. Plantations have long

been abolished, but their remnants can be seen today in the targeting of Black people by the

police (Reese and Sbicca, 2022). Not only has the carceral state shaped Black communities'

relationship with the food system since slavery, now the food system is also reinforcing the

relationship to incarceration and the carceral state. When discussing the abolition of police and

prisons, we must also discuss the need to abolish unhealthy food systems (Reese, 2020a).

A primary example of the relationship between food access and incarceration and

recidivism is the Farm Bill. Amendments to the bill have repeatedly completely cut access to

food stamps, known as SNAP, for people who have been convicted of violent crimes (Cooper,

2013). These cuts to SNAP make it nearly impossible for formerly incarcerated people to provide

for their families, leading to high recidivism rates when they return to ways they made money

prior to being incarcerated, which in many cases could be the reasons they were incarcerated.

More than 630,000 people are released from prison annually, with forty-three percent of that

population returning to prison within the first year (Francois, 2018). Cutting access to food

15

stamps is one way to throw people back into prisons or other dangerous situations to make

money.

Along with losing access to SNAP, people who have previously been incarcerated are

more likely to live in food swamps and food apartheid areas (Testa, 2018). Not only does this

increase the likelihood of going into dangerous situations to make money, but it also exacerbates

health disparities in formerly incarcerated people (Testa, 2018). The United States’ history of

mass incarceration has led to wide health disparities targeting Black and brown people. These

disparities can be linked to poverty, poor employment, unstable housing, and of course, food

insecurity (Dong and Feng, 2021).

The families of incarcerated people are also impacted by unjust food systems. The

economic losses caused by incarceration can impact any children involved and can shape their

relationship to healthy food for the remainder of their lives (Gifford, 2019). One study found that

a parent’s involvement with the criminal justice system can be linked to the entire family’s risk

of food insecurity (Santos et al., 2022). Unlike adults, children are not able to travel to areas

outside their neighborhood for different food options. A lack of access to healthy food has also

been linked to low test scores in children from low-income backgrounds (Rowe, 2022).

Incarceration, food apartheid, and food insecurity have countless impacts on children and

families.

Food Access, Incarceration, and Health When discussing communities that are at high risk for diet related diseases, it is important

to note that they were made that way intentionally. Mariana Chilton states that “they are not

‘unhealthy communities.’ They were made unhealthy. They are minoritized communities. They

are discriminated against communities. And that's policy. Over multiple generations, over many

years, hundreds of years in the making. Communities are made unhealthy by the policies that are

16

put into place” (Chilton, 2022). The health of residents living under food apartheid also plays a

vital role in their life expectancy, relationship to incarceration, and their overall well-being in

neighborhoods that were designed against them.

The greatest killer of Black Americans in the United States is not violence but diet related

diseases. Multiple factors coincide to make this a reality: poverty, unclean air and water,

stressors, and of course unhealthy foods. Additionally, studies have found that other factors that

disproportionately impact Black Americans can also lead to a high-risk factor for diet related

diseases (Olokotun et al., 2022). According to one study,

There is strong evidence linking heart disease to socioeconomic status, drug use, cigarette

smoking, unemployment, and stress. In addition to these factors, incarceration has also

emerged as a variable of interest that may be associated with chronic health conditions

such as heart disease. Evidence shows that individuals who are currently incarcerated

have a higher burden of heart disease compared to individuals in the general population,

raising concerns about the relationship between exposure to incarceration and heart

health (Olokotun et al., 2022).

Studies also report that having an incarcerated family member can have an adverse effect

on health. Even if an individual has not been incarcerated themselves, studies show that women

with incarcerated partners are at higher risk for depression, diabetes, and hypertension compared

to those with non-incarcerated partners (Widra, 2021). Additionally, children whose parents are

incarcerated have higher rates of mental health problems and substance use disorders (Widra,

2021). All of these factors impact Black Americans at higher rates than their white counterparts,

and all can lead to lower life expectancy. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, incarceration does not

only impact those who are incarcerated, but their families as well.

17

Figure 3. The Physical and Mental Health of People with Incarcerated Family Members. Source: Prison Policy Initiative

18

Figure 4. Rates of Incarcerated Family Members by Race. Source: Prison Policy Initiative

Living under food apartheid has a notable impact on an individual’s health and well-

being. Among low-income families in food apartheid areas, low access to healthy foods

contributes to poor nutrition and can lead to higher rates of obesity (Meeks and Alexis, 2021).

Additionally, Black Americans, who are also more likely to live in food apartheid areas, have the

highest rates of diet related diseases such as diabetes and hypertension (Meeks and Alexis, 2021).

As always, redlining also plays a role. In a new study conducted by the Journal of the

American College of Cardiology, researchers found that as neighborhoods' redlining grade

decreased, the rates of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking increased (Rodriguez, 2022).

Further, researchers found that while health insurance can help people with diet related diseases

manage their illnesses, nearly twice the number of adults did not have health insurance in D-

graded areas compared to residents in A-graded neighborhoods. This proves the association

between redlining and health outcomes. (Rodriguez, 2022).

It is clear that food access, redlining, and incarceration can all have adverse effects on a

person’s health, even if the person themselves is not incarcerated. The fact that a family

member’s incarceration can negatively impact someone’s cardiovascular health is evidence that

incarceration has far reaching consequences beyond keeping one person in prison. Above that, if

a person has lived under food apartheid and other impacts of redlining their entire lives and is

later incarcerated, the odds are invariably stacked against them, health wise. Not only do redlined

and food apartheid neighborhoods offer meek healthy food options, but so too do prisons.

Unfortunately, Black and poor Americans are most likely to live under all of these conditions,

and their health is most likely to suffer the most as a result. Food is arguably the most critical

19

‘thing that promotes health’, and in urban areas food choice is often severely constrained

(Eisenhauer, 2001).

Food Sovereignty and Food Justice Food sovereignty is defined as the right of those who grow food to create their own food

and agriculture systems, as well as maintain access to healthy foods (La Via Campesina, 2018).

In urban areas of food apartheid, food sovereignty is seen as a solution. La Via Campesina, the

organization responsible for launching the concept of food sovereignty in 1996, says that:

Food Sovereignty is about systemic change – about human beings having direct,

democratic control over the most important elements of their society – how we feed and

nourish ourselves, how we use and maintain the land, water, and other resources around

us for the benefit of current and future generations, and how we interact with other

groups, peoples, and cultures (La Via Campesina, 2018).

The current food system we live under proves a need for food sovereignty, which first gained

momentum in the Global South, where global food corporations have exploited the livelihoods of

small and local farmers for years (Alkon and Agyeman, 2011). Experts have argued that food

sovereignty is the first step to food security, which many low-income communities have been

fighting for. Demands for global food sovereignty are largely anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist,

and seek to create food systems that are sustainable, equitable, and healthy (Holt Gimenez and

Shattuck, 2011).

Urban agriculture can be a method by which people living in food apartheid areas achieve

food sovereignty (Colson-Fearon and Versey, 2022). According to a study done in Baltimore,

participants of a neighborhood urban garden noted that if supported, urban agriculture could: (1)

address food access inequality; (2) support community empowerment; (3) encourage health

promotion; and (4) provide sustainable access to healthy food (Colson-Fearon and Versey, 2022).

While food sovereignty began as a mechanism to support farmers in the Global South, it has

become a means for Black Americans living under food apartheid to combat food insecurity.

20

Race plays a pivotal role in the food sovereignty movement. America’s history of food

and agriculture is so entrenched in racist codes and policies, that it is impossible to discuss, and

more importantly achieve, food sovereignty without addressing race explicitly (Cooper, 2018).

Not only was American land first stolen from Indigenous people, but that land was then

maintained by enslaved African Americans, who later were denied the opportunity to purchase

their own land, and even later were used as labor again through the prison system (Roots of

Change, 2022). The history of food growth and farming in the United States is couched in racism

and anti-Blackness. Many food sovereignty and food justice activists have argued that America’s

racist food systems have in fact contributed to inequitable access to healthy food (Alkon and

Mares, 2012). As seen in the six pillars of food sovereignty below, food sovereignty values food

providers- especially Black and brown people who have been forced to grow food for the

wealthy and struggled in the process.

21

22

Figure 5. The Six Pillars of Food Sovereignty. Source: La Via Campesina, 2018.

The food justice movement has been vital in the United States over the past several years.

Due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, hunger rates increased—as did a need for food

justice. According to the organization Feeding America, most Americans who were most

impacted by the pandemic were food insecure or at risk of food insecurity prior to COVID-19

and are now facing even greater hardship since COVID-19 (Feeding America, 2021). In response

to rising hunger, unemployment, disrupted supply chains, and unaffordable food costs, the food

justice movement became more popular throughout the country. Many community fridges and

pantries were opened as a response to the pandemic, including the West Philadelphia People’s

Fridge. Community gardens also became more popular as a result.

23

Food justice activists use food as a tool for social justice (Sbicca, 2018). While food

security and access have been a part of the larger conversation on food for many years, food

justice brings to light the fact that low-income and impoverished communities are often erased

from the narrative, and in fact are the most harmed by the current food system (Alkon and

Agyeman, 2011). These communities are erased from the narrative due in part to the racism that

keeps them from being able to achieve food sovereignty. Food justice activists also argue that,

due to racist federal policies such as redlining and land theft, Black and brown communities are

completely excluded from the US food system (Alkon and Mares, 2012). These same

communities lack local access to healthy foods, and the healthy foods that they do have physical

access to are often outside their price range (Winne, 2009).

Leah Penniman, a scholar-activist, and farmer, frequently writes about liberation theology

in farming. Liberation theology generally refers to a theology applied to the core concerns of

marginalized communities in need of social, political, or economic equality and justice (B.

Bradley, 2016). It is a vital tenet of food justice and the need for food sovereignty. Penniman and

other Black farmers are working to increase equity and access in agriculture. Research has found

that Black people working in the food system earn less wages than their white counterparts,

receive less benefits, and live with less access to healthy food (Penniman, 2018, 8). Creating an

anti-racist and anti-carceral framework within farming is more than necessary. Food can be a

way to examine the prison system by exploring the role that the plantation plays in food and

nutrition (Reese and Sbicca, 2022).

Urban Gardening and Agriculture Urban gardens have provided produce and nutrition to many since World War II. During

the war, ‘victory gardens’ began being planted around the country. These gardens were providing

24

the only produce that many households could get at the time, due to the low supply of consumer

goods (Hall, 2020). In the present day, urban farms are still a source of nutrition and produce in

food apartheid areas and food swamps. In places like West Philadelphia, many community

members have grown and maintained gardens as a way to combat food insecurity. Urban farms

and gardens can improve food security by providing fresh and renewable access to grains, nuts,

fruits, and vegetables (Krishnan et al., 2016).

Not only does gardening increase access to healthy foods, but it can also help build

community and prevent violence. In North Carolina, a community came together to build a

garden on the land of an abandoned prison. The project aimed to help keep young men out of

prison, and the organizers found that over the years of 2011 to 2016, of the twenty-four youth

who were involved, the garden was 92 percent effective in preventing incarceration and

recidivism (Cooke, 2020).

For incarcerated members of society, gardening has become a rehabilitation device

(Chennault and Sbicca, 2022). In the United States, at least 662 adult prisons have gardening and

farming activities, the stated purpose of which are rehabilitative, financial, and reparative

(Chennault and Sbicca, 2022). However, many scholars and experts argue that the system of

agriculture in prisons is as exploitative and harmful as it is rehabilitative (Hazelett, 2021). Due to

the violent history of slave labor and agriculture in the United States, it is arguable that prison

agriculture is an extension of this history (Chennault and Sbicca, 2022). Additionally, prison

agriculture is part of a campaign of green prison reforms that do not acknowledge or challenge

the need to abolish the prison system entirely (Hazelett, 2021).

The history of food growth and food systems in the United States is built on systems of

racism and oppression. Black Americans were brought to the US as slaves to grow food, but once

25

slavery was abolished, they too were forced out of farmlands. Over the course of the last century,

Black American farmers have lost a total of 12 million acres of farmland, due in large part to

racist federal policies like redlining, and inequitable social practices (Meredith, 2022). In recent

years, Black Americans have worked to remake these harmful systems, and take back their land.

In 2010, food activist Karen Washington began the annual National Black Farmers and Urban

Gardeners Conference, which brings together over five-hundred Black farmers (Penniman, 2018,

3).

Conclusion A plethora of research suggests the links between food access, incarceration, and health.

Black and brown people in the United States fight different injustices daily, and access to food is

just one piece of the puzzle. Of all the violence these communities face, the biggest killer of

Black Americans is not gun-related violence, but diet related diseases. These diseases impact

low-income and Black communities at higher rates, in part due to their proximity to food

apartheid, food insecurity, and food swamps (Penniman, 2021). The entire system is working in

tandem to target Black Americans.

In my research, I aim to fill the gaps left by scholars. Where past literature has examined

formerly incarcerated peoples’ lack of access to healthy food, I want to explore the relationship

between a lack of access to healthy food and future incarceration rates. I will apply this

foundational literature to a case study of Philadelphia to examine the ways that redlining and

food apartheid can be linked to incarceration. Ultimately, it is my hope that my research can start

to build a pathway for healthier communities that can help shape an abolitionist future.

26

Chapter 3: Planning Discrimination: How Redlining Shaped Food

Apartheid in Philadelphia

Redlining and Food

8

Figure 6. A Redlining Map of Philadelphia. Source: National Archives and Records Administration via UrbanOasis.org

Philadelphia has always been a ‘free’ city and was in fact a destination for many runaway

slaves escaping the South (Waterman, 2016). In Philadelphia, many Black families were able to

rebuild their lives and shape new communities away from the oppressive Jim Crow laws of the

8Redlining maps classified neighborhoods in 4 categories: A – “Best” areas, colored green; B – “Desirable” areas, colored blue; C – “Declining”

areas, colored yellow; D – “Hazardous” areas, colored red.

27

South. However, systemic racism followed them. Despite being free, the North had racism of its

own (Waterman, 2016). In the 1930s, the system of redlining began in Philadelphia and

elsewhere in the United States. A map of the way Philadelphia was redlined can be seen above in

Figure 6. Although the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was passed to fight redlining, its impacts are

still felt today. Today, Philadelphia neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s have the

highest rates of gun violence, poor education, food apartheid, heat islands, and unclean air

(Ackley, 2020; Jaramillo, 2020; Li and Yuan, 2022; Palmer et al., 2021 Rhynhart, 2020). All of

these factors work in tandem to create neighborhoods where low-income Black and brown

people live in poor health, and the built environment in Philadelphia intentionally made these

neighborhoods poor and unhealthy. Food justice author and organizer Alison Alkon tells me that

because of redlining, “you'll find relationships if you look at incarceration rates by zip code and

you map them onto areas of food apartheid. They're going to line up with poor education systems

and every marker of marginalization that we see” (Alkon, 2023).

With less access to food, Black people in redlined neighborhoods are more likely to steal

it (Rangel, 2020). This leads to more encounters with police and the carceral justice system.

Kanav Kathuria, who has extensively researched the links between incarceration and food for the

Maryland Food and Prison Abolition Project, says that “the same neighborhoods that were

subject to historic oppression are bearing the brunt of food apartheid right now, and they are

hyper incarcerated” (Kathuria, 2023).

Supermarket redlining has been a large issue in Philadelphia, so much so that in 2004, a

statewide financing program called The Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative (FFFI)

began in order to build supermarkets and grocery stores in minority urban and rural

neighborhoods (Reinvestment Fund). FFFI ran from 2004 to 2010 and ended because the limited

28

funds had run out. The aim of the program was to remove financing obstacles and lower

operating barriers for supermarkets in poor communities; reduce the high incidence of diet-

related diseases by providing healthy food; and stimulate investment of private capital in low-

wealth communities (Reinvestment Fund). According to the Reinvestment Fund, a partner in the

project, “FFFI attracted 206 applications from across Pennsylvania, with 88 projects financed as

of June 2010. In total, more than $73.2 million in loans and $12.1 million in grants were

approved. Projects approved for financing were expected to bring 5,023 jobs and 1.67 million

square feet of commercial space.” This project was able to provide supermarkets to many

neighborhoods in need, but unfortunately did not have enough funding to continue past 2010.

Redlining, food access, and health also intersect in myriad ways. Research has found that

diet and cardiovascular related diseases disproportionately impact people who live in both

redlined and food apartheid neighborhoods (Mujahid et al., 2021). A study on the links between

redlining and cardiovascular health found that redlining has a lasting impact on cardiovascular

risk for Black Americans (Mujahid et al., 2021). The report on the study states that: “...similar to

the institution of slavery, redlining is one manifestation of structural racism that drives health

outcomes today. This work underscores the necessity to investigate structural racism as a root

cause of racial/ethnic health inequities” (Mujahid et al., 2021).

While the relationship between cardiovascular health and redlining are vastly

understudied, the authors of the report did find links, including the way that redlining has played

a role in segregation, poverty, and low-income levels—all of which have previously been linked

to negative cardiovascular health (Mujahid et al., 2021).

It is clear that redlined neighborhoods are disinvested in and this impacts residents on

multiple different levels. The drug war, education, public health, and food access are all ways in

29

which redlined neighborhoods are disadvantaged as compared to their non-redlined counterparts.

While it is difficult to map out a direct causation between redlined neighborhoods, food, and

incarceration, it is clear that redlined neighborhoods suffer from public health detriments in

many ways- all that are linked to the carceral justice state. We cannot discuss the ways that

redlining and food access and incarceration have impacted neighborhoods without taking a step

back and seeing how the three are linked.

Food Apartheid + Food Swamps Not only does low access to food indirectly lead to interactions with the criminal justice

system, but redlined neighborhoods are also likelier to also live under food apartheid. Ashley

Gurvitz tells me that in many cities, “certain neighborhoods have better outcomes around food,

and certain neighborhoods do not, and it's another transformative form of redlining, just to keep

people behind” (Gurvitz, 2023).

The violence of redlining, food apartheid, and incarceration are all linked in their purpose

to keep Black people and neighborhoods unhealthy. In fact, Kanav Kathuria says that “prisons

and food apartheid are really two formations that stem from the same core of racial capitalism

and premature death being the outcome of both of them” (Kathuria, 2023). The violence of food

apartheid is exactly why the term has replaced ‘food desert’ in recent years. Ashley Gurvitz is

clear about her definition of the term, telling me that “I’m not afraid to say it's apartheid, because

there are so many oppressive structures in place with it” (Gurvitz, 2023). The way apartheid

systemically works to oppress people of lower social mobility makes it the perfect descriptor for

how food access is mapped out in neighborhoods.

Many Philadelphia neighborhoods can be described as food swamps. A majority of the

city’s food stores sell only unhealthy foods, and the density of these stores increases as the

neighborhood income decreases (City of Philadelphia, 2019). Further, across Philadelphia, the

30

number of stores selling unhealthy foods outnumbers the number of stores selling healthy foods

by nearly 10 to 1 (City of Philadelphia, 2019). Figure 7 depicts how the majority of food retailers

in Philadelphia are corner stores, chain convenience stores, and gas stations.

Figure 7. Philadelphia Food Retailers. Source: Neighborhood Food Retail in Philadelphia, 2019

Neighborhoods that have a history of disinvestment and poverty are not just losing access to

healthy foods, but also have disproportionate access to foods that can lead to health issues and

illnesses. Figure 8 shows the amount of low-produce supply stores around Philadelphia, of which

corner stores are many.

31

Figure 8. Number of Low-Produce Supply Stores, Philadelphia. Source: Neighborhood Food Retail in Philadelphia

Figure 6

32

As figure 6 shows, in comparison with figure 8, neighborhoods that had lower HOLC

classifications in 1937 now have higher concentrations of low-produce supply stores, also known

as corner stores and mini markets. South Philadelphia had especially low redlining grades, and

now has especially high numbers of corner stores.

According to experts, adults over 50 who live in food swamps had a higher risk of stroke

compared to those who do not (Yang, 2023). Additionally, adults with diabetes who live in severe

food swamp areas had higher hospitalization rates (Phillips and Rodriguez, 2019). It is believed

that the availability of healthy vs. unhealthy foods can influence dietary outcomes, meaning that

living in a food swamp can impact a person’s likelihood of developing diabetes or other diet

related diseases and making them more vulnerable and prone to diabetes. (Phillips and

Rodriguez, 2019). According to an article about supermarket redlining and health, poor and

Black communities have the odds stacked against them and their long-term health in various

different ways, including low access to healthy foods: “Health hazards can always be either

exacerbated or ameliorated by social conditions, and the low status and diminished opportunities

that the urban poor experience aggravate the simple facts of low income and few food sources.”

(Eisenhauer, 2001).

Areas living under food apartheid and food swamps are dealing with multiple macro-

aggressions on a daily basis. Their neighborhoods face constant disinvestment, they are living

under poor economic conditions, and they have little to zero access to quality foods and

healthcare. All of these factors will undoubtedly impact a person’s long-term health, especially as

it pertains to their hearts. The fact that redlining, food apartheid, and food swamps can all have a

detrimental effect on cardiovascular risk is not an accident– it is by design. Later on, I will

33

discuss how incarceration can also affect cardiovascular health. All of these factors are

inextricably linked.

Access to Resources Not only do redlined neighborhoods have limited access to healthy foods, but also to

many other resources that could improve their health, well-being, and development. The Food

Trust, a local food-providing organization in Philadelphia, has been working hard to provide

healthier food options to people in these neighborhoods. The Food Trust is working to create

healthy corner stores, to bring healthy foods to food swamp areas in and around Philadelphia as

part of their Healthy Corner Store Initiative. According to the Food Trust website, the

organization provides fresh produce to these stores, as well as training, equipment, and

marketing materials to help sell the items (The Food Trust, 2022). Food Trust employee Wayne

Williams tells me:

When you look at the demographics of those that are incarcerated and where they live or

where they grew up, we know for the most part, most of them live under food apartheid.

And so, food is one aspect of that environment. But there's a whole list of other

circumstances that leads them to [incarceration.] Education, of course, is one of them.

These neighborhoods don’t just lack proper access to food, but also education, and they

are often left out of political conversations. So, with all this negligence, it's only natural

that most of the people we find in these neighborhoods are not only suffering from food

inequality, but they’re also suffering from other inequalities. That's what leads them, in

many cases, to the prison system (The Food Trust, 2023).

The quality of education in redlined neighborhoods is unfortunately low. A 2022 report found

that schools in the Philadelphia area are among the most segregated in the United States,

meaning that Black and brown students in Philadelphia are receiving substandard education

(Mezzacappa, 2022). According to the report, Philadelphia spends less per student than many

surrounding districts, even though most Philadelphia students, who are low-income students of

color, generally have more needs (Mezzacappa, 2022). The report states that:

34

American schools today are… highly segregated by economic status. Racial redlining of

neighborhoods has been replaced with exclusionary zoning policies that keep low-income

families out of certain communities. Housing markets are heavily impacted by school

district boundaries and attendance zones. And school choice policies create an uneven

playing field for families of different socioeconomic means trying to access different

schools (Potter, 2022).

Lack of education in these neighborhoods does not stop at schooling. Many residents in these

neighborhoods also lack education about the types of foods they should be eating, the nutrients

their bodies require, and the unhealthiness of the foods they are eating. According to a 2012

study that examined the health literacy and nutrition behaviors of a sample of adults enrolled in

SNAP, the researchers found that only 37% of participants had adequate health literacy. Less

than half of the participants reported using nutrition labels when purchasing food. Questions that

required numeracy skills were the most challenging for participants. Race and parental status

(whether or not the participants had children) were found to be significant predictors of health

literacy (Speirs et al., 2012). Many Philadelphians are users of the SNAP program: while

Philadelphia residents make up only 12% of Pennsylvania’s population, they represent 26% of

the 1.9 million Pennsylvanians enrolled in the program (Prihar, 2023).

Another consequence of redlining and White Flight impacting food access in Philadelphia

is the current public transit system, otherwise known as SEPTA (Southeastern Pennsylvania

Transit Authority). In the late 1930s and early 1940s, federal transit funding in Philadelphia was

dedicated to the development of freeways to surrounding suburbs for the white and wealthy

residents who could afford to live there (Segregation by Design). The systematic development of

highways and freeways across the United States was part of a larger urban renewal plan, which

targeted low-income Black communities for removal (Stromberg, 2015). “Highways were a tool

for justifying the destruction of many of these areas” (Stromberg, 2015). Urban renewal and

35

highway development are also part of the long-term legacy of disinvestment in low-income

Black urban communities due to redlining.

While Philadelphia removed many trolley stations that low-income and Black residents

depended on, they continued funding regional rail lines that serviced the same white, wealthy

suburbs (Segregation by Design). According to Segregation by Design, the Philadelphia budget

is servicing the suburbs at the expense of the inner city. While only 11% of commuters use the

regional rail, 40% of SEPTA’s entire budget is dedicated to it. Additionally, the city and county

of Philadelphia is contributing 83% of regional rail’s operating costs, while the four surrounding

suburban counties only contribute 17%. In other words, according to Segregation by Design, “the

city is paying for suburban transit service at the expense of local service” (Segregation by

Design).

In addition to transit redlining and disinvestment in Philadelphia, many low-income

residents also don’t own cars. According to U.S Census Data, Philadelphia is one of the most car-

free cities in the country (Otterbein, 2013). While many residents are car-free by choice, poverty

also plays a role. Philadelphia’s rate of poverty was over 26% in 2013, while 33% of families did

not own cars (Otterbein, 2013). Many families are unable to afford the costs of a car, leaving

them with few options to travel- including to supermarkets outside their neighborhoods. The

United States Department of Agriculture has measured Americans’ access to healthy food by

using ½-mile and 1-mile demarcations to the nearest supermarket for urban areas, 10-mile and

20-mile demarcations to the nearest supermarket for rural areas, and vehicle availability for all

tracts (USDA, 2021). When a family does not own a car, their access to food is impacted

severely.

36

All of these barriers- lack of education, public transportation, and car ownership- are

factors in a person’s access to food and their relationship to policing and prisons. These barriers

are a primary reason why so many residents in Philadelphia have taken up the cause of feeding

their neighbors. Matt Stebbins of the Coral Street Fridge tells me that “people are drowning in

many different waves. They don’t have access to a phone that they can apply for benefits on,

they don’t have access to transportation, or childcare, or caseworkers, many times English isn’t

their first language. And then they face barriers to food on top of everything else” (Coral Street

Fridge, 2023).

Gentrification Gentrification9 in lower class cities also plays a role in the access that residents have to

different resources, compared to their wealthier counterparts. When white and wealthy people

move back into cities to gentrify them, it changes the entire landscape of the city and which

resources go where. It also changes the way police interact with residents. Black residents might

have lived in a neighborhood much longer than the white people who are gentrifying the area,

but they are policed more due to the color of their skin. Simply put, according to Nicholas

Freudenberg, “there isn’t a simple relationship between percent Black and policing because of

the variable of gentrification. When middle class people move in, they want more policing, and

that policing is focused on Black and brown youth” (Freudenberg, 2023).

Because of the role that race and poverty play in segregation in Philadelphia, the only two

outcomes of gentrification for Black and brown residents are forced removal or over policing

(Harrison, 2022). According to Philadelphia based think tank Economy League, “residents in

9The process whereby the character of a poor urban area is changed by wealthier people moving in, improving housing, and

attracting new businesses, typically displacing current inhabitants in the process (Oxford Dictionary).

37

gentrifying neighborhoods note that social norms and surveillance—particularly in the form of

policing—change as previously low-income neighborhoods undergo the gentrification process”

(Smith and Shields, 2021).

According to the same report, non-gentrifying tracts had the largest proportion of stops,

followed respectively by gentrifying and non-gentrifiable tracts. In fact, in 2019, non-gentrifying

tracts—which are predominantly low-income with higher concentrations of Black and Latinx

residents—saw an average of 57 stop-and-frisks for every 100 residents. The scale of stops

greatly exceeds the violent crime rate (Smith and Shields, 2021).

Figure 9. Police Stops and Gentrification from 2014 to 2019. Source: Smith and Shields, 2021.

For decades while inner cities were ignored and disinvested in, they lacked access to

amenities like supermarkets, gardens and parks, and quality public schools. With the influx of

middle-class white people moving into these cities, these resources start to appear, but are only

accessible for the new residents—not the low-income Black people who were there before them.

38

While a common refrain might be that low-income neighborhoods should get these

resources before being gentrified, unfortunately these resources can lead to gentrification as well

(Johnson, 2021). A study found that planting trees was associated with gentrification over time,

otherwise known as green gentrification (Johnson, 2021). In fact, Alison Alkon believes that

community gardens can contribute greatly to green gentrification. She says that “sometimes

realtors and people who are really interested in urban development see a community garden and

think ‘oh, somebody cares about this place. I could open up a fancy coffee shop and make some

money or, I could sell the houses around here for more money, or I can put this in my

advertisement for why this neighborhood is up and coming’” (Alkon, 2023). It seems that lower-

income residents are caught in the trap of wanting to keep their homes versus wanting better

access to amenities for their health.

Gentrification can have a positive effect on food access in many communities, bringing in

new food outlets and grocery stores, but on the other hand is also responsible for driving out

affordable food retailers and bringing in higher priced restaurants and supermarkets to service

newer residents (Rick et al., 2022). Additionally, gentrification increases housing prices, making

many families more rent burdened and less able to purchase healthy foods (Rick et al., 2022).

The new food stores in these communities are not targeted towards long term residents who are

suffering from food insecurity; instead, the high-end grocery stores such as Whole Foods and

Trader Joes can contribute to their being priced and pushed out of their homes (Blackwell, 2016).

Gentrification is also a result of decades long redlining and disinvestment. Redlining has

devalued real estate in inner cities so much that it has now become profitable for investors to

come in and start making money by tearing them down and building higher priced homes (World

Food Policy Center). After decades of disinvestment that resulted in poor food access, education

39

quality, and greenery, gentrification makes clear that low-income Black and brown residents are

not worth investing in but their neighborhoods are once they become populated with middle class

white people.

Urban Gardening and Agriculture A popular response to food apartheid is urban gardens and farms. In Philadelphia, there

are hundreds of community gardens around the city, with new ones popping up each year

(Farming Philly). Urban agriculture is a form of resistance in line with the long tradition of Black

rebellion. It is a way for Black people living under food apartheid to take back control of the land

and control of the food that they are able to eat (Kathuria, 2023).

Community gardening can unfortunately play a role in green gentrification. Not only can

it make neighborhoods more desirable for new real estate, but also to new residents. However,

gardening does have a positive impact on crime. A study found that ‘sprucing up’ vacant lots by

cleaning up trash and mowing the grass curbed gun violence in Philadelphia neighborhoods by

nearly 30% (Dengler, 2018). The study reports that:

Neighbors felt safer. Residents living near lots converted to parklike environments

perceived less crime in their neighborhoods and reported feeling 58% less fearful of

going outside than people living near unimproved lots. People who lived near renovated

lots also used the spaces to relax and socialize 76% more than inhabitants near

unmodified lots (Dengler, 2018).

Community gardening can be a source of food sovereignty for many people living under food

apartheid. Andrea Vettori, the founder of Philadelphia’s Sanctuary Farm, says that residents in

the neighborhood are eating more greens than ever because of a pride that comes from knowing

that the food was grown in their own community (Sagner, 2021). Food sovereignty is becoming

more and more vital in an economy where not many people have access to healthy foods, and the

healthy foods available are outside their budget. Food organizers believe that food sovereignty is

40

the only way to ensure food security. Janice Tosto, who runs a community pantry out of North

Philadelphia, says that “we need to have systems in place where people have access to land so

that they can learn to grow their own food, and they can teach their neighbors to grow food”

(Tosto, 2023). According to Tosto, food sovereignty is one of the few ways to ensure that a

person will always have access to food.

On the contrary, other organizers and experts argue that food sovereignty on its own

cannot solve food insecurity. Because of the changing climate Philadelphia’s soil does not ensure

long term farming prospects. Gardening and food sovereignty also does not combat poverty.

Mariana Chilton is passionate about combating the root causes of poverty and hunger and

believes that community gardens do not do that. She tells me that “gardens help to ease the pain

of poverty, but they don't end poverty” (Chilton, 2022). The outcome of food sovereignty is

feeding people, but not addressing why they are hungry in the first place. There must be policies

in place to help people who are systematically underfed.

In our conversation, Chilton is adamant about the ways that poverty and hunger must be

addressed. She says that while there is a burgeoning community garden movement, its impacts

are limited. Without access to home kitchens or electricity, an outside garden is futile for many

people. The real impact of a garden, she says, is that it builds community:

They build a sense of resilience, and they help people connect with nature and connect

with their food and demonstrate respect and understanding the rhythms of life. Their

natural world is deeply important. But you're not going to see that making a change on

food insecurity, because food insecurity measures whether people have enough money for

food, so the measurement is different. (Chilton, 2022).

Still, urban gardening can be a way for Black Americans to reclaim their relationship

with farming and soil. Post slavery, Black farmers were evicted from farmlands in the South,

unable to own land and use their agriculture skills to support their families (Meredith, 2022).

41

However, with the recent boom in popularity of urban gardens, Black Americans are finding

their way back to the practice, according to Philadelphia urban gardener and food justice activist

Ashley Gripper:

Farming is not new to Black people. While some dominant modern narratives talk about

urban agriculture as an innovative way to build community and fight food insecurity,

Black folks in this country have been growing food in cities for as long as they have lived

in cities. Before that, our ancestors lived in a deep relationship with the land. Growing

food is a tool for dismantling systemic oppression (Gripper, 2020).

Many other Black Americans have been disconnected from farming, bearing inherited trauma

from oppression (Kuang, 2020). In their case, urban gardens are not the balm that they are to

others. They should still have access to healthy food in their neighborhoods, whether they want

to dig in the soil or not (Alkon, 2023).

42

Chapter 4: How Food Access Determines Police Presence

Introduction

I grew up in Queens, New York, which I find similar to my current neighborhood in West

Philadelphia. There are many similarities between the two cities, but one that seems to stick out

to me the most is the plethora of corner stores, also known as bodegas. Growing up, I would

walk home from school on Northern Boulevard in Jackson Heights and have at least three

bodegas to choose from when I wanted to purchase an after-school snack. The bodegas were

usually family owned and operated, and mainstays of the community. When I walk into similar

corner stores and bodegas now, in Philadelphia, I feel a pang of nostalgia for those days- but also

the realization that the situation is different in Philadelphia than it was for me in Queens. In

Queens, while there were many bodegas and corner stores, there were also multiple food markets

and grocery stores in the same neighborhoods. This is not the case for food swamp

neighborhoods in Philadelphia.

Criminalization of Corner Stores Many of the unhealthy food retailers in Philadelphia are corner stores and mini markets in

poorer neighborhoods. Corner stores have multiple links to the carceral justice system. Many of

them do not accept SNAP and EBT—which eliminates many poor people’s ability to shop

there—and they are also over policed.

In Cedar Park, a West Philadelphia neighborhood, a corner store that recently opened in

March 2023 has a sign in the doorway that reads “This location is under 24/7 live surveillance to

the 18th Precinct. Any illegal activity will be prosecuted. Drug dealers will be prosecuted to the

fullest extent of the law.”

43

Figure 10. A corner store threatening police action in West Philadelphia. Source: Photo taken by the author.

Due to the nature of these neighborhoods that were redlined, historically disinvested in,

and now live under poverty and food apartheid, many residents are forced to resort to activities

that are deemed illegal to earn money and feed their families. Corner stores have largely become

overpoliced because employees and police tend to assume the worst when dealing with Black

and poor residents. A recent and widely known example is seen in the death of George Floyd in

Minneapolis. Floyd was purchasing cigarettes from a corner store when the clerk noticed that the

bill he used to pay was counterfeit, and called the police when Floyd left the store. This act led to

the events that ended Floyd’s life (Bogel-Burroughs and Healy, 2021).

The painful and completely avoidable death of George Floyd signals a grave example of

the role that corner stores and their policing play in the oppression of Black Americans, as well

as the double standards that Black Americans face. When the government and banks