[💡10] How to avoid the Four Horsemen of the Future of Work

Like this project

Posted Nov 1, 2023

LinkedIn article about the Future of Work through the lens of "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse".

Likes

0

Views

11

From time to time I watch old episodes of shows I grew up with to soothe my nerves. As a child of the 90s the OG Charmed is one of my go-tos. The other day I watched episode 2x21, Apocalypse Not, featuring the good old staple of all fantasy media – the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse have been a popular trope in fantasy TV shows and movies for decades, serving as harbingers of the end of the world. Their menacing presence makes them a perfect fit for the genre, appearing in everything from The Simpsons to X-Men.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are figures from the book of Revelation in the Christian Bible. They are described as four horsemen, each representing a different aspect of the end of the world: war, famine, pestilence and death. The exact origins of the myth are uncertain, but it is believed to have been inspired by earlier apocalyptic myths and legends from various cultures. Over time, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse became a recurring theme in art, literature, and popular culture, particularly in the fantasy and horror genres. Their foreboding reputation and the sense of impending doom they bring have made them a popular choice for writers and filmmakers looking to create tension and drama in their stories. So now I’m using the characters to create tension and drama regarding the future of work.

While the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse make for great entertainment, their real-life counterparts in the workplace of tomorrow (read: today) are quite insidious. They may not have the same ominous ring to their names, but they're just as destructive. The Horseman of War, in the workplace of today, are obstinate leaders who resist change and view business as a battlefield, using war analogies like "our sales team needs to be on the front lines" or "we're in a war for talent". This mentality does not pass the vibe-check and inevitably leads to conflict and tension. Poor communication and fragmentation within and between hybrid teams represent Famine. Failure to examine the impact of changing work arrangements can leave teams feeling starved for connection and collaboration. In what has been referred to as a “Burnout Epidemic”, Pestilence can be seen in the apparent rise in chronic work-related stress; and no amount of mask-wearing or sanitising can keep the unrelenting pressure of modern work from infecting employees with stress and exhaustion. As for Death, well, organisations face certain death, should they not be mindful of changes and developments in the future of work that may result in reduced employee engagement. So let's saddle up (yes I went there), and use the metaphor of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, to examine how one might guard against common challenges associated with the future of work.

The Horseman of War: Resistance to change

You know the type. The one who speaks on everyone’s behalf without taking the time to actually speak to everyone. The one who fetishizes hardship by romanticising the past. The one who makes sweeping statements like "I do think for a business like ours, which is an innovative, collaborative apprenticeship culture, [remote work] is not ideal for us. And it’s not a new normal" (David Solomon, CEO – Goldman Sachs). The one whose BFF is the status quo.

If you squint and tilt your head to the side, you’ll see that resistance to change is really just resistance to losing control. Sure, you can make the argument that having control over one’s life is a basic emotional need and that leaders are humans too. Of course, if you do make that argument but then you would be guilty of gaslighting because you and I both know it’s not about control over your own life it’s about control over others. In the future of work, the Horseman of War lives in views among leaders that anything new or different presents a threat to their position of power. They cling to the old ways of doing things, even if those ways are no longer effective, and they discourage others from exploring new ideas or taking risks.

A tell-tale sign that the Horseman of War has a VIP suite in the company stables, is when it seems like winning is everything. If the complexities of organisational life in the new normal are consistently reduced to short-term victories, long-term change is unlikely. If the organisation’s leadership claims to care about innovation, sustainability, or whatever else, but doesn’t have the receipts to back it up, claims are just that – claims. A surefire way to detect the clippity-clop of this Horseman’s approach, is to check the ‘strongly agree’ column for the pulse survey item “If I don’t meet my targets, my ass is grass”. If you are not allowed to include this item, incorporate these into your apocalyptic early detection system:

Lack of communication: If organisational leadership is not open to discussing changes and the reasons behind them, it may be an indication of their resistance to change.

Consistently rejecting new ideas: If organisational leadership consistently rejects new ideas or proposals without providing any valid reasons or alternative solutions, it may indicate a resistance to change.

Avoiding risk: If organisational leadership is risk-averse and prefers to stick to what has worked in the past, they may be resistant to change.

Lack of experimentation: If organisational leadership is not open to experimenting with new ideas or approaches, it may indicate a resistance to change.

Rigid hierarchies: If organisational leadership insists on maintaining rigid hierarchies and structures that stifle innovation and creativity, it may be an indication of a resistance to change.

Punishing failure: If organisational leadership punishes failure instead of encouraging experimentation and learning from mistakes, it may indicate a resistance to change.

Now that we've assessed the likelihood of coming face-to-long-face with the Future of Work Horseman of War, what steps can we take to avoid it? Glad you asked. Do this:

Review performance management policy and instruments: Redefine ‘good performance’ as more than the bottom line and reward collaborative behaviour. Remember Piper’s club in the original Charmed series? P3? You know what else has 3 Ps? The triple bottom line, namely ‘People, Planet, and Profit’. Coincidence? I think not!

Build an appreciation for diversity into the structure of your organisation: Here I don’t mean just diverse representation – yes that too – but also diversity of thought. From time to time change-averse individuals will find a way to slither into positions of power. Having organisational structures that promote and reward diversity of persons and thought helps mitigate the potential adverse impacts of such leaders.

Create spaces of psychological safety: Hear me out! I know the notion of psychological safety has been so overused in organisational settings that it's become the corporate equivalent of 'thoughts and prayers' - it sounds good, but rarely leads to meaningful change; but in order to embrace change, one must be willing to take risks. Unfortunately, this is not up for debate, as we have seen in the last few years that the future of work is constantly evolving. So, unless your employees can see evidence that taking calculated risks, making mistakes and learning from them, doesn’t threaten their livelihoods, it is unlikely that new ways of working will be welcomed and your organisation will suffer for it.

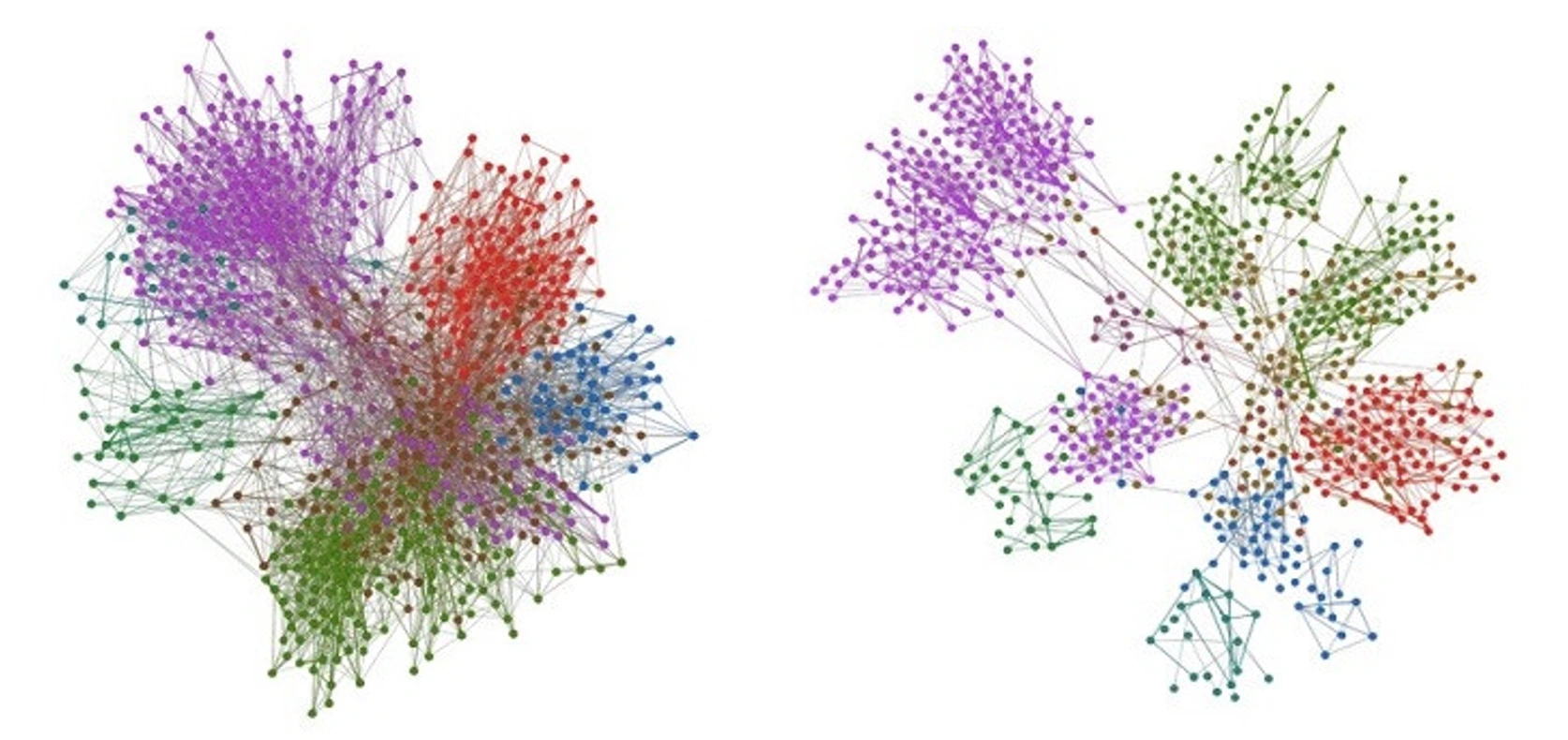

The Horseman of Famine: The Neighbourhood Effect

According to the recent work of Michael Arena and others, a loss of social connectivity has led to the erosion of both bonding and bridging social capital after prolonged virtual work. This has resulted in socially disconnected ‘neighbourhood’ structures that are more dependent on a limited set of local interactions – leaving employees starving for connection…clop-clop…clop-clop 🐴. Such losses in social connectivity have in turn necessitated greater efforts to traverse network voids to openly share ideas, information, and communication. The image below depicts the fragmenting consequences of failing to evolve organisational structures and processes alongside changing work practices.

Source: HR Exchange (2022) The Neighbourhood Effect: Implications of Hybrid Work

Now, the Horseman of Famine might have you believing that the future of work needs to revert back to the…well…‘past of work’. You’d be wrong in thinking that. That hybrid work is here to stay is not up for debate – it’s the new reality. So what we need to do is work towards understanding these new dynamics better, so that we can evolve ways of working more holistically. The so-called ‘Neighbourhood Effect’ is still a new concept, but what we know is this: After extended periods of hybrid work arrangements without any other changes in how individuals and teams interact, employees not only become detached from each other, but also from the broader organisational purpose. In fact, according to research done by Reward Gateway, HR leaders believe employees are 41% less connected to colleagues and 32% less connected to their organisation’s purpose.

While the Horseman of War can be identified by the foul stench of hostility it leaves in its wake, identifying the Horseman of Famine is less about a malodorous presence, and more about the absence of inviting aromas. If these mixed metaphors are confusing, just use this checklist to spot the culprit:

Taken-for-granted practices that produce employee isolation: To what extent are employees isolated from people other than their direct team or manager? In a hybrid world, it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking a quick daily check-in is sufficient for satisfying our natural need for social interaction. We need broader engagement, both in quantity and quality.

Reduced collaboration: This one goes hand-in-hand (read: hoof-in-hoof) with employee isolation. How is work organised? Is work structured in a way that everyone just “does their own thing” to “make things easier” in a hybrid environment? What you gain through short-term efficiencies, you’ll lose through long-term social capital is erosion. Don’t fall for it!

Silos start emerging: Insufficient cross-functional interactions can create silos and impede the flow of information and ideas across the organisation. This can lead to massive long-term problems where the organisation becomes so fragmented that cross-functional value chains completely break down.

There are limited opportunities for socialisation: In the future of work, organisations can not shirk responsibility in creating spaces for socialisation (even if these spaces are virtual). On top of formal deliverables, employees cannot be left to their own devices to engage with colleagues. This is the corporate equivalent of burying your head in the sand.

Increased reliance on formal communication channels: If employees rely almost exclusively on formal communication channels, such as email and video conferencing, rather than informal interactions, such as phone calls, text messages, and even Instagram likes, this could be a sign that social capital is eroding.

Decreased trust: Dead giveaway! If employees are less likely to trust their colleagues and managers, this could be a sign that social capital is deteriorating.

Social fragmentation in organisations limits growth and adaptive capacity. As social connections erode, an organisation limits its access to new ideas and insights, potentially stifling speed and execution as local social interactions are restricted. So how does one avoid the Horseman of Famine in the future of work? Like this:

Promote safe spaces for informal communication: Encourage employees to communicate regularly in an informal manner. Encourage employees to engage in informal interactions without fear of being perceived as “slacking off”.

Foster collaboration: This needs to be formalised and incorporated into how work is organised and performance is measured. Business processes and practices should be redesigned for the future of work, so that it includes deliberate opportunities for cross-functional collaboration.

Encourage knowledge-sharing: Like collaboration, knowledge-sharing requires a formal component. The nature of knowledge sharing is so that it cannot be fully formalised, but space can be carved out in formal duties and responsibilities that allow for the sharing of expertise.

Ensure equitable access to resources: Few things demoralise people like trying to do good and not having the tools to do so. This becomes even more urgent of a consideration for geographically dispersed teams. Management must be held accountable for ensuring that all employees have access to the same resources and opportunities, regardless of their location or work arrangement.

Shift HR centricity from human capital to social capital: Individual skills and abilities are insufficient for addressing the complex challenges of the future of work. HR professionals should focus on creating value for the organisation by developing and leveraging employees' social capital. This is only possible through identifying and building strong relationships between employees across different departments and locations.

Embrace alternative organisational structures: The hierarchy is no longer fit for purpose in the future of work. In fact, it poses a significant risk for the Neighbourhood Effect occurring. Matrix and network organisational structures are more suitable for the hybrid work environment and do not rely on the flawed assumptions underpinning conventional organisational structures.

The Horseman of Pestilence: Burnout

COVID wasn’t even properly over when the Burnout Epidemic trotted into the room like:

Image source: RuPaul’s Drag Race (2013) Season 5, Episode 1

The best expression I’ve heard, critiquing the pervasive overworking cult, is that we are no longer working from home, but living at work. Burnout is not new. People have been talking about Burnout for a hot minute. Herbert Freudenberger is known for some of the earliest work on the phenomenon in the 1970s. Freudenberger described Burnout as “to fail, wear out, or become exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources”. More recently, the World Health Organization recognised Burnout as a distinct “syndrome that results from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”. Some of the most notable work on the subject has been done by Christina Maslach and Michael Leiter, which is evident in the manner in which the WHO define Burnout, namely “feelings of energy depletion, increased mental distance from one’s job, and reduced professional efficacy”.

The problem with the discourse around Burnout in the future of work is that it is consistently framed as an employee issue, when in fact it’s an organisational issue. Yet, the internet is firewall-to-firewall articles with titles like “7 tips to avoid Burnout” and “The biggest mistakes that lead to Burnout”. I’ll tell you what your mistake is: working for a company that thinks you can time-manage away oppressive workloads and unsupportive managers. Miss me with that BS.

Burnout may manifest as individual symptoms, but it is the result of systemic dysfunction. In order to identify Burnout – or at least the level of risk for Burnout occurring among your workforce – and in order to avoid it from occurring in the first place, we can draw on the work of Christina Maslach and Michael Leiter. To try and get a whiff of the Horseman of Pestilence in the future of work, look for:

High emotional exhaustion: Work-related stressors can result in feelings of being drained or depleted, both physically and emotionally. If you notice increasing reports of employees feeling tired, behaving irritably, or displaying apathy, it could be as a result of high emotional exhaustion.

High depersonalisation: Feelings of detachment or being disengaged from others, particularly in a work-related context, could be an indication of heightened depersonalisation. Managers should carefully monitor cynical sentiments within their teams, as well as indifference towards clients or colleagues. Difficulty empathising with others is also a dead giveaway for high depersonalisation.

Low personal achievement: An enduring sense of disappointment or frustration with one's own performance or productivity, despite putting in significant effort at work could be an indicator of Burnout. Signs of low personal achievement may include feeling ineffective or unproductive and having difficulty finding a sense of meaning or purpose in one's work.

While the above are well-known indicators of Burnout, focusing only on symptoms is a bit like putting the cart before the horse (yes, I did that). Testing for Burnout has a time and place, but as with most issues of wellness, prevention is better than cure. To avoid Burnout, we can use another framework proposed by Maslach and Leiter:

Workload: Design work in a manner that is reasonable and sustainable, taking into account employees' workload capacity and skills. Provide adequate support and resources to help employees manage their workload more effectively.

Control: Empower employees with decision-making power and autonomy over their work. Provide opportunities for employees to participate in decision-making and offer support and guidance to help them make decisions effectively.

Reward: Ensure that employees feel recognised and valued for their work by providing regular feedback and recognition, as well as fair and equitable compensation. Create a positive work environment that values employee contributions.

Community: Foster a supportive and inclusive work environment that promotes collaboration and teamwork. Provide opportunities for social interaction and support, and encourage open communication and feedback.

Fairness: Ensure that organisational policies and practices are fair and just; and are perceived as such. Provide clear and transparent guidelines and procedures, and treat employees with respect and empathy. Address any concerns or grievances promptly and fairly.

Values: Create a work environment that promotes a sense of purpose and meaning by communicating the organisation's values and mission clearly. Provide opportunities for employees to engage with their work in a meaningful way, and encourage personal and professional development.

The Horseman of Death: Low employee engagement

Popular media will have you believe that the future of work’s Horseman of Death isn’t the Horseman of Death, but simply a passing fad galloping by. I don’t mean to sound dramatic, but honestly, the manner in which low employee engagement is discussed in popular discourse makes me want to hurl myself in front of a herd of wild horses. Employee engagement is a well-established focus area in organisational studies, yet news outlets and online content creators insist on coming up with cutesy nicknames for the same thing. Seriously, "The Great Resignation"? "Quiet Quitting"? "Quiet Moonlighting"? "Career cushioning"? Spare me. These gimmicks only divert attention away from the root cause underlying observed phenomena, namely low employee engagement. Low engagement equals organisational death, so let’s giddy-up, shall we?

Disengaged employees are a silent killer for companies, leading to decreased productivity, low morale, and increased staff turnover. Disengaged employees are emotionally disconnected from their work and don't feel invested in the success of the organisation. At this point you might think this sounds like Burnout, but low engagement is a horse of a different colour (yep, went there too). Low employee engagement represents a lack of motivation, commitment, and willingness to make an emotional investment in one's work, while Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and mental distress caused by prolonged stress and overwork. Thus, while they may have similar symptoms, they have very different underlying causes and require different approaches to address and prevent.

So, why such discontent? Well, according to Vox, companies are raking in record profits while front-line workers are enduring poor working conditions and even worse pay. In addition to employees resigning in droves, large organisations such as Starbucks, Apple, Amazon, and Trader Joe's have also seen a stampede in unionisation efforts towards better pay and working conditions. The jig is up – simply claiming that “your people are your most valuable asset”, is not enough to stop the exodus of your top talent…quiet or otherwise. Listen for the subtle snorts of the Horseman of Death by looking at:

Decreasing productivity: Low employee engagement can result in decreased productivity due to a lack of motivation and commitment. Keep an eye out for teams or individuals who consistently miss deadlines or fail to meet performance goals. Sometimes it’s not a simple ‘disciplinary matter’. No amount of written warnings will make your employees more engaged.

Increasing staff turnover: Disengaged employees are more likely to seek employment elsewhere, leading to high turnover rates. In a complex and unpredictable future of work attracting and retaining the appropriate skillsets is crucial for an organisation’s survival. Track turnover rates and identify any patterns or trends in terms of which departments or roles are experiencing higher turnover.

Little, if any, innovation: Employees are less likely to contribute innovative ideas or solutions if they are not engaged in the mission and purpose of what it is the organisation wants to achieve. In the future of work, things simply change too rapidly for organisations to not actively pursue innovation. Monitor the level of employee participation in idea-generation sessions or innovation initiatives to identify ‘innovation dead zones’.

That said, organisations need to take proactive steps to prevent disengagement and promote employee engagement. Sure, you can use the list above to identify problematic areas and attempt to remedy it, but consistently maintaining engagement is always a better approach than to periodically try and fix poor engagement. You may do so through:

Designing purpose-driven work: Create a work environment that emphasises purpose and highlights the impact of employee contributions to the organisation's overall mission. Offer opportunities for employees to connect with the purpose of their work and communicate how their work is making a difference in- and outside of the organisation. An easy way to do that is to create links to important socio-economic issues such as inequality, sustainability, and public health.

Skills development: Provide opportunities for employees to develop new skills and advance their careers within the organisation. Show that you value employee growth and development by offering training programs or other professional development opportunities that are in line with developments in society and predictions for the future.

Flexible work arrangements: Offer flexible work arrangements, such as remote work or flexible scheduling, the 4-day work week, unlimited leave, among others. In the future of work lip service to ‘holistic people management’ is no longer an option. Employees need to feel supported in maintaining work-life balance if organisations wish to keep them engaged.

Fair compensation: This one is kind of a no-brainer. And by ‘no-brainer’ I mean when I look at what some organisations consider ‘fair compensation’ I’m left wondering if the person who came up with it has a brain or not. Wealth inequality is higher than it has ever been and it cannot coexist with an engaged workforce. There are many new alternatives organisations may consider, such as idiosyncratic deals for high-performers, but essentially what it comes down to is paying people enough so they don’t need a side hustle to be able to cover basic expenses for themselves and their families. I can’t believe that actually needs saying but here we are…

Employee recognition: Regularly recognise and reward employees for their contributions and achievements, both individually and as part of a team. Celebrate successes and milestones, and show that you value and appreciate your employees' hard work and dedication. Note, this is NOT a substitute for fair compensation.

Explore new alternatives to engagement such as “Thriving”: Like many other organisations, after the pandemic, Microsoft decided to make a change in how it approached engagement and introduced the concept of “Thriving”. They define Thriving as “being energised and empowered to do meaningful work”. Personally, I am not entirely convinced this is a distinctly different construct from engagement, but I do applaud the effort to look into ways in which we can improve on old ways of doing things in the future of work. I encourage other organisations to do the same and I look forward to seeing further developments in this area of research.

Beware the prophesied Four Horsemen of the Future of Work: the Horseman of War, Famine, Pestilence, and Death, who ride rampant in the hybrid landscape, threatening to sow discord, disconnection, burnout, and low engagement. Choose to ignore the prophecy and you may find yourself facing the following fate:

![[💡11] Coaching and the Future of Work: Less new things, more...](https://media.contra.com/image/upload/w_400,q_auto:good,c_fill/awr2oslg4ikidqbyem8i.avif)