Hand Washing in Kenya’s Informal Settlements and the Impact on …

This paper explores the importance of governments, key stakeholders and donors in the WASH sectors working collaboratively towards improving and increasing access to safe water in the informal settlements towards mitigating the risk of transmission of COVID-19.

Background

As of August 2020, over 1 million persons have contracted COVID-19 in Africa with a death toll of 28,051. COVID-19 has not only affected the health sector, but has had a spillover effect on most socio-economic rights of individuals. Among other personal prevention measures, The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends hand hygiene which involves frequent handwashing using soap and water or the use of an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, as being the most effective actions in reducing the spread of pathogens and infections including COVID-19. However, as a UNICEF study has shown, only 14% of the population in Kenya has access to hand-washing facilities, including soap and water at home.

WHO goes on to state that in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, it is necessary to have WASH and waste management practices that are evidence based and consistently applied. A lack of access to WASH facilities, apart from increasing the spread of COVID-19, infringes on the human right to access Water and Sanitation. This contribution emphasises the importance of integrating participatory human rights-based approaches to WASH programming so as to effectively respond to COVID-19 and other future pandemics.

The United Nations (UN) recognizes the access to water and to sanitation as a human right, essential in every human’s life. The right to water entitles everyone to have access to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The right to sanitation entitles everyone to have physical and affordable access to sanitation in all spheres of life that is safe, hygienic, secure, and socially and culturally acceptable. A rights-based approach to pandemics is required to address inequalities and discriminatory problems that are present in the right to water and sanitation and which may impede the process of development.

Despite the existing resources being directed to the sector, an estimated $14 billion in investment in water supply and $5.4 billion in investment in urban sewerage infrastructure are needed in Kenya over the next 15 years to close financing gaps in achieving universal access to water and sanitation. An estimated 20 out of 50 million Kenyans source water from ponds, shallow wells and rivers which are not clean while 35 million Kenyans lack access to improved sanitation. Furthermore, 9.4 million Kenyans drink directly from water sources that are contaminated (the third highest in Sub-Saharan Africa), and about 5 million of the population still practice open defecation due to the lack of access to sanitation facilities such as toilets.

The individuals that are affected are both in rural and urban areas. In informal settlements, the majority of households lack access to the public water supply and rely on private water vendors, owing to the privatisation of water supply systems by unscrupulous and corrupt individuals. According to a grassroot human rights defender located in Mathare, an informal settlement located in Nairobi, Kenya, access to water during this time of the ongoingCOVID-19 pandemic is “not just a basic right, but a question of life and death.” Lack of adequate water coupled with a lack of handwashing vessels and soap negatively affects hand hygiene which is essential in curbing the spread of COVID-19. A survey carried out by the Office of the High Commissioner Human Rights (OHCHR) in Kenya reveals that only a minority of respondents in informal settlements have regular access to public water supply, which is regulated, and less costly. The study also revealed that 1.4% of the government national budget for the period 2014 to 2018 was allocated to water and sanitation, with an estimated 92% of this allocation being directed to development and water infrastructure projects. However, a majority of these projects have either not commenced, have stalled or have been abandoned altogether; as such the impact on improved access to water on the population residing in informal settlements remains unclear. A limited supply of water forces slum residents to prioritize water use to the most urgent need which is for consumption. Anne Nyokabi , a slum resident in Kibera informal settlements in Nairobi explains it this way: “We don’t have enough water to drink and cook our food, so where will we get water to wash our hands frequently?”

Innovation

The UN has classified the right to water and sanitation into five normative dimensions: availability, accessibility, quality and safety, affordability, and acceptability. Availability means a sufficient quantity of water for personal and domestic use and a sufficient number of hygiene facilities particularly for hand washing, menstrual hygiene, children faeces’ disposal and food preparation. In increasing access to WASH facilities, efforts need to be geared towards either increasing the number of WASH facilities or reducing waste of limited WASH resources.

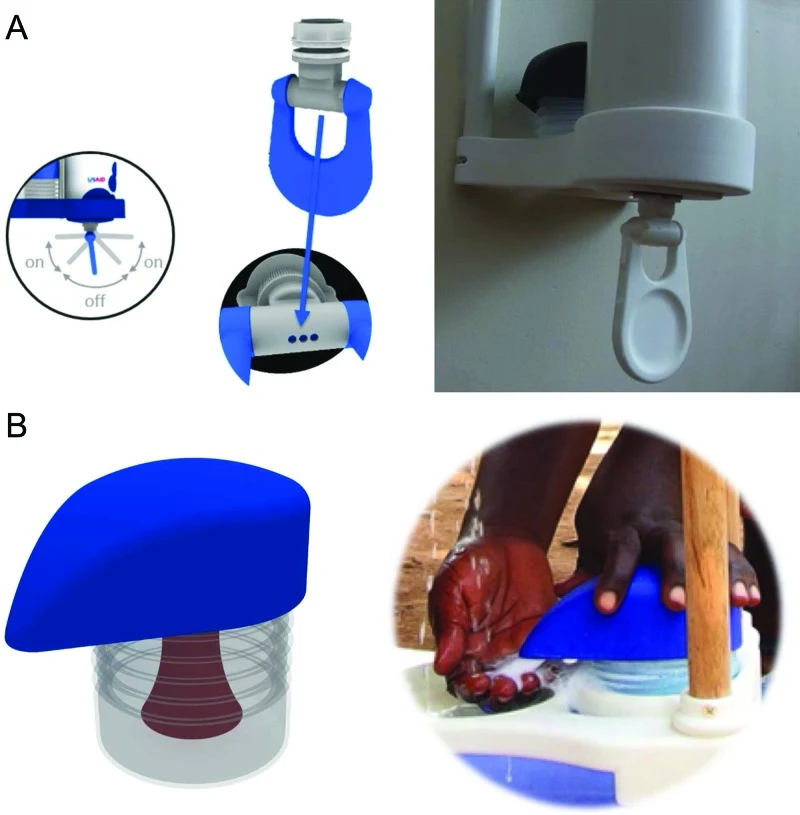

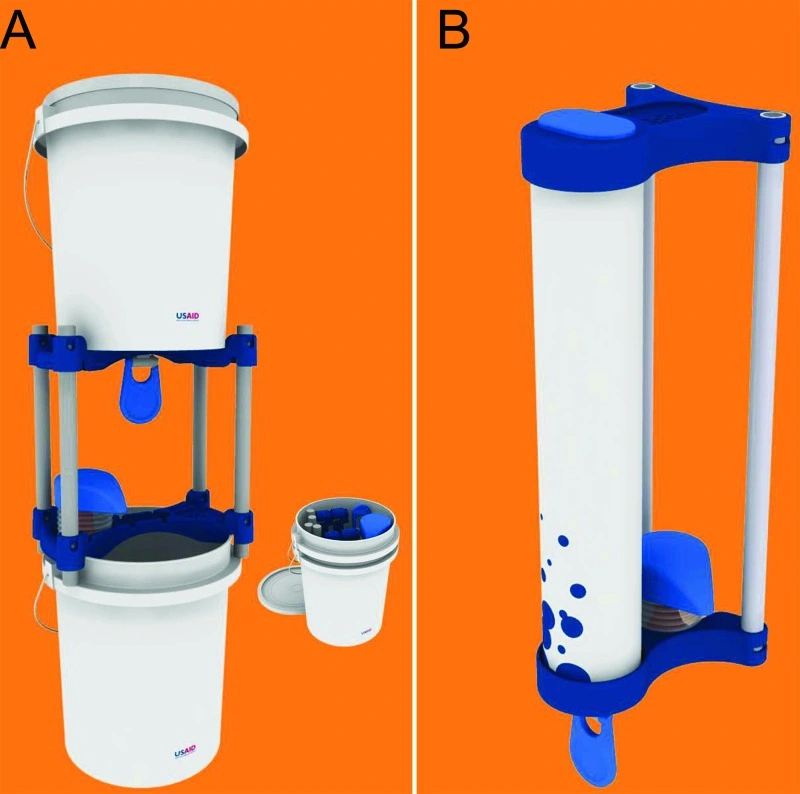

One such innovation is the Povu Poa station (translated to ‘Cool Foam’ in Kiswahili language), a water-efficient, soap-frugal and portable handwashing system. The Povu Poa station comes with an innovative soap foam dispenser that conserves soap, and a “swinging water” tap that is hygienic, easy to use, and conserves water. This handwashing innovation is ideal for use in informal settlements where majority of residents are faced with limited water supply and finances. A research finding reveals that people are more likely to wash their hands if hygiene facilities are readily available. The ‘Swing Tap’ enables people to use the tap hygienically with the back of their hand. The swing tap dispenses water from 3 holes; this is controlled based on how far forward or backward they pull/push the tap. The Povu Poa Soap Foamer works by creating foam by mixing soapy water and air.

Figure 1: A demonstration of how the handwashing station works © IPA and Catapult Design

Figure 2: The Povu Poa Bucket and Swing model © IPA and Catapult Design

Povu Poa stations provide optimal use of water and hand hygiene resources thus increasing access to water and hygiene for individuals. Povu Poa stations have recorded great results in increasing handwashing by 32% in schools and 75% in clinics. Additionally, the stations are relatively more affordable cutting down costs of handwashing facilities by an estimated 77%.

Access to water and sanitation is a human right which has proven to be even more critical particularly during these challenging times when the continent is faced with a major pandemic. The lack of access to safe water and sanitation facilities has a spillover effects to other human rights such as the right to education, housing, health, life and work. A rights-based approach to the provision of safe drinking water informs individuals, particularly the poor and marginalised of their legal rights and empowers them to realise these. Through community participation and the planning and design of water and sanitation programmes, water and sanitation services are assured to be relevant and appropriate, and thus ultimately sustainable.

Cite as: Ngao, Jacqueline. "Hand Washing in Kenya’s Informal Settlements and the Impact on Prevention of COVID-19", GC Human Rights Preparedness, 17 September 2020, https://gchumanrights.org/preparedness/article-on/hand-washing-in-kenyas-informal-settlements-and-the-impact-on-prevention-of-covid-19.html

Written by Jacqueline Ngao

Jacqueline Ngao is an intern at the HEFDC Group in Nairobi, Kenya. She is currently in her final semester at the University of Nairobi studying Economics. Having undertaken other WASH and hand hygiene related projects, this experience and knowledge inspired the choice of topic for this discussion paper.

Add a Comment

Disclaimer

This site is not intended to convey legal advice. Responsibility for opinions expressed in submissions published on this website rests solely with the author(s). Publication does not constitute endorsement by the Global Campus of Human Rights.

CC-BY-NC-ND. All content of this initiative is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Like this project

Posted Jul 4, 2023

This paper explores the importance of governments, key stakeholders and donors in the WASH sectors working collaboratively towards improving and increasing acc…

Likes

0

Views

38