Exploring Happiness and Meaningfulness

Like this project

Posted Aug 4, 2025

What is the secret ingredient to have a happy and meaningful life?? Science kind of has an answer!

“Do everything with intention.” “Money can’t buy happiness.” “Find meaning in all.”

We’ve all heard these quotes or something similar, especially with our newfound focus on healthy, happy living. But what do these feel-good mantras really mean? Sure, hearing a Zen yogi say these after lying in shavasana for a few minutes makes us feel a little more at peace, but how do we actually find these things in our day-to-day life? I may not have the answers (shocking, I know), but I believe the key to a happy life is finding meaning. Helpful, I know. But hear me out...

We know that the relationship between a happy life and a meaningful life can be hard to determine. Some of us may view one as more important than the other, while others may believe that the two depend on each other (spoiler: it’s the latter). Now here’s an added layer: figuring out what makes a happy or meaningful life can shape whether one seems more important — or if they go hand in hand. Super simple, right? I argue that these two ideas are interdependent, specifically that happiness stems from meaningfulness. Let’s break it down.

First, it's helpful to understand what exactly “happiness” and “meaningfulness” mean. For this thought experience, we’re going to use Diener’s definition of happiness and Ryan and Deci’s definition of meaningfulness:

Happiness, or hedonic well-being, is characterized by frequent positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and high life satisfaction (Diener, 1984).

Eudemonic well-being is concerned with living in accordance with one’s true self and fulfilling one’s eudaimonic well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001).

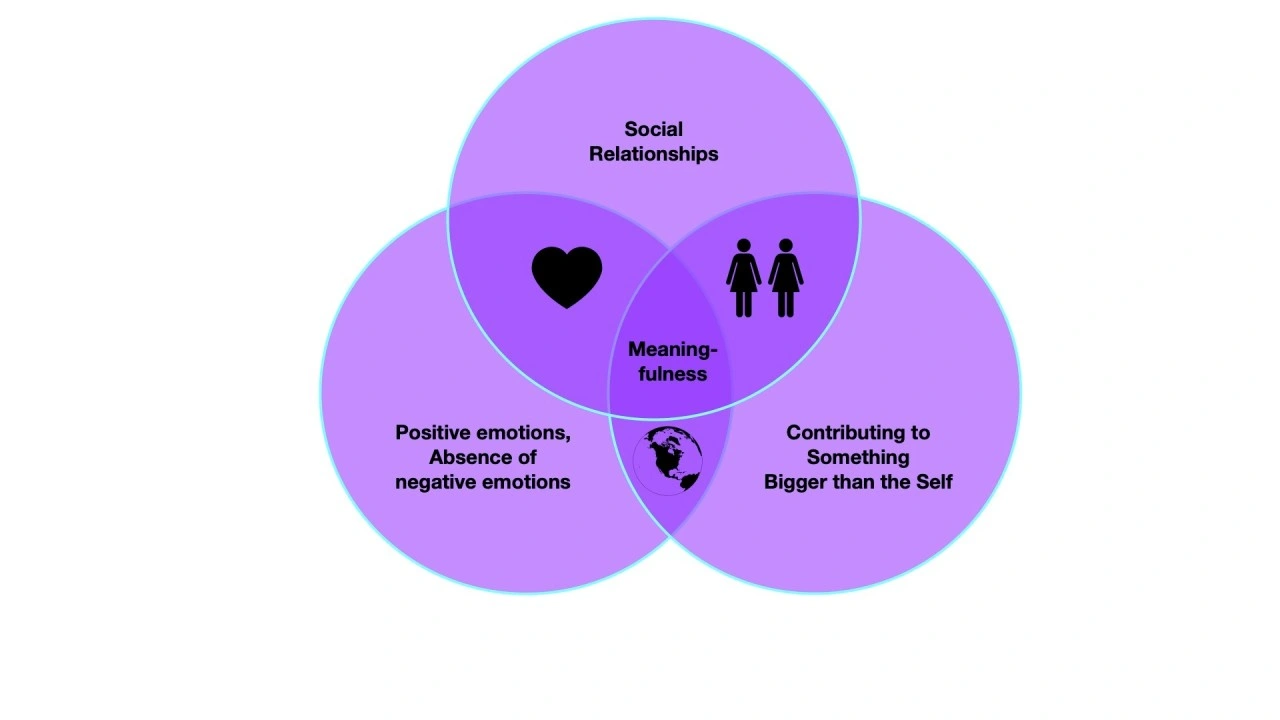

In layman’s terms, happiness can be defined by generally having positive emotions (e.g., calm, excited, happy, etc.), rarely having negative emotions (e.g., anger, sadness, ennui, etc.), and being generally satisfied with one’s life. Meaningfulness, on the other hand, is more about feeling that you have purpose, achieve personal growth, and contribute to things larger than yourself.

Now let’s put these concepts into tangible examples. Typical examples include family, friends, loved ones, partners, and other socially based interpersonal relationships. And for good reason, Mackenzie and Baumeister explain that meaningfulness is developed through the social and cultural aspects of life, mostly from relationships and interactions with others (Mackenzie & Baumeister, 2014, pp. 25–37). To back this up, research

conducted by Lambert et al. found that “68% ranked family as their primary source of meaning in life and another 14% ranked friends as the primary source, so that for 82% of participants, personal relationships were the primary source of meaning” (2010, as cited in Mackenzie and Baumeister, 2014). They go on to state that to have a meaningful life, four requirements must be met: purpose, value, efficiency, and self-worth (Mackenzie & Baumeister, 2014, pp. 25–37).

Happiness in life is often misidentified as physical things, such as items and money, which causes people to spend more time and money on obtaining objects to increase happiness. While this may give a short-term dopamine boost, these things don’t lead to long-term true happiness (Nielsen T.W.). Research by Post, Neimark, and Seligamn shows that the highest levels of happiness that remain stable are produced through having meaning in one’s life (2011, 2007, & 2002, as cited in Nielsen T.W, 2014).

So, happiness stems from meaning, and meaning is founded in relationships. Now what does this mean?

From a psychological standpoint, having meaning in life is to build loving social relationships with others. But as we’ve all experienced, the relationships that provide meaning change as we age. In younger adulthood, people tend to have more friends than they do when they’re older (Cavanaugh & Blancher-Fields, 335). In older adulthood, people tend to become more focused on their family relationships, work, and responsibilities. This change in focus and life satisfaction factors may show a greater sense of meaningfulness and happiness in older adults. While young adults rely on friendships to find meaning and therefore happiness, older adults show more focus on aspects of meaningfulness.

Many people find great life satisfaction in contributing to a family and raising children

Raising children can be seen as “contributing to something greater than yourself”

Pursuing a dream career can be contributing to society at large and can provide

On the reverse, being in a toxic, unwanted, or stagnant career can strongly limit life

Now fast forward 10 years. Do parties and large friend groups sound more satisfying than having a job you don’t hate and focusing on relationships that hold weight?

Don’t worry – we don’t get boring as we age, and we aren’t shallow when we’re young. If the “key” to happiness is having a meaningful life, then our relationships and interactions with our most valued people are vital. While the fact that happiness stems from meaningfulness remains consistent throughout life, the focus on what makes a meaningful life changes as we age. When we’re young, we may be more focused on having lots of friends and lots of fun, but as we grow, we begin to focus on the quality of these dynamics, as well as other elements of our lives (family, career, growth, something bigger than us). We build a fuller understanding of what gives us meaning - and that only comes from, well. Living.

Happiness is the presence of positive emotion, lack of negative emotions, and having overall life satisfaction

Meaningfulness is based on having purpose, personal growth, self-realization, and contributing to something bigger than yourself

Happiness stems from having meaning, and meaning largely stems from interpersonal relationships and interactions

Nielsen, T. W. (2014). Finding the keys to meaningful happiness: Beyond being happy or sad is to love. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 113–132). Routledge.

Mackenzie, M. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Meaning in life: Nature, needs, and myths. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 25–37).