Wearable Devices and Insomnia Management Study

Introduction

Insomnia is a chronic condition where an individual regularly has problems sleeping, typically treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (NHS, 2024). However, there is another method which encourages at-home treatment of insomnia and sleep-deprivation; sleep wearables which determine and record sleep via sensor-reported methods such as polysomnography (PSG), which measures brain-wave activity, and actigraphy (AG), a measurement of physical activity (Spina et al., 2023). This case study aims to see whether providing support for interpretation of sensor-reported sleep data and monitoring sleep using wearable devices has a significant effect on managing insomnia symptoms, as it has shown for healthy individuals in the past (Berryhill et al., 2020).

Challenge

There are often differences between self-reported and sensor-reported sleep perceptions in individuals with insomnia, which is most often referred to as sleep-wake state discrepancy (SWSD) (Bensen-Boakes et al., 2022). The most common discrepancies are present in sleep onset latency (SOL; time to fall asleep) and wake after sleep onset (WASO; waking up from sleep but not “getting up” (Shrivastava et al., 2014)), and total sleep time (TST). This can prevent effective treatment from occurring, since unresolved disagreement in how sleep methods are affecting the individual can make self-regulation of sleep much more difficult regardless of medical intervention.

Method

This study was a randomized controlled trial conducted by a team at Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, Monash University, Australia. 113 English speaking individuals over the age of 18, scoring greater than 10 on the Insomnia Severity Index, took part. Individuals who had shift-work schedules during the duration of the study, significant symptoms of untreated or insufficiently treated sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, restless legs syndrome, circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders, moderate or high suicidal ideation or had used Fitbit or Dreem (the software used in this experiment) less than a month before the trial were excluded from the trial. The measurements were done with reference to the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS). The exact models of software used were Fitbit Alta HR (Fitbit Inc., 2017 release), worn on the non-dominant hand, and Dreem headband (Rhythm SAS., version 1), worn on the head whilst sleeping. Participants also recorded their sleep perceptions in a sleep diary. (Spina et al., 2023)

Pre-Study

Interested participants took part in a screening interview via telephone and, if successful, were randomly assigned to either the control group or intervention group (57 members in the intervention group, 56 members in the control). They were then asked to complete a baseline questionnaire assessing the primary measure (Insomnia Severity Index: ISI) and multiple secondary measures, namely sleep-related impairment (SRI), sleep disturbance (SDs), depression and anxiety. (ibid)

Week 1

The intervention group attended a feedback session conducted by a Provisional Psychologist and supervised by a Clinical Psychologist. This feedback session covered differences between sleep variables measured using self-report and sleep wearables, as well as SWSD and its relevance to insomnia.

The control group attended a sleep education session conducted by the provisional psychologist. The session covered psychoeducation about sleep and overall sleep hygiene. (ibid)

Week 2-5

The intervention group was asked to give a sleep report each following week of the trial, giving data on TST, sleep efficiency, SOL, WASO, and sleep stages throughout the past week. In week 2 and week 5 (1 and 4 weeks after baseline), both control and intervention groups received check-in calls to manage any troubleshooting issues and encourage regular and honest adherence to the test. (ibid)

Post-study

Both groups were asked to complete a survey assessing the metrics assessed earlier at baseline. They were also given a final group-blind telephone call during this assessment and were assessed for clinical insomnia in accordance with DSM-5 criteria. After the post-survey and return of research equipment, participants received up to 70 AUD for participation. They received 20 AUD for completing the questionnaires and 10 AUD for each week the experiment collected data for 7 nights.

Results

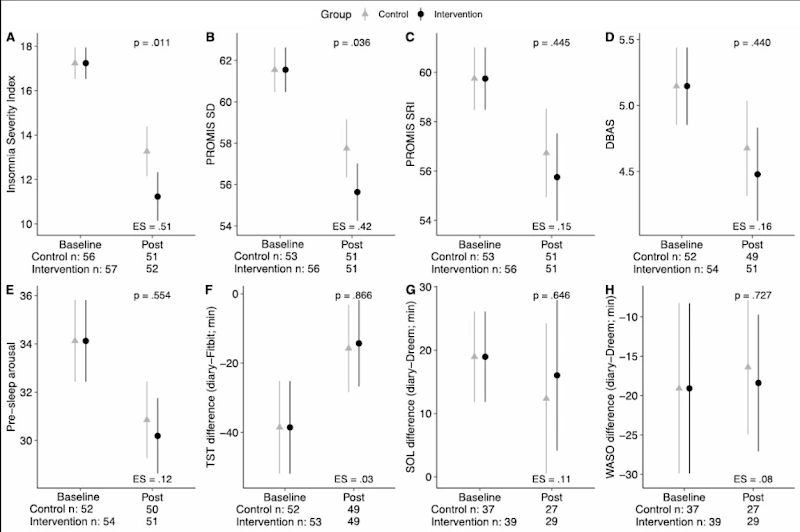

The results in the figure (Spina et al., 2023) show the intervention group had significantly lower ISI (Graph A) in comparison to the control group (p=0.011) post-study, suggesting a greater reduction in insomnia symptom severity. They also had a significantly lower SD (Graph B), indicating better sleep quality (p=0.036). 58.8% of intervention participants and 78.4% of control participants met criteria for DSM-5 Insomnia Disorder. All other metrics did not display significant differences (ibid).

Evaluation

Intervention participants had a lower ISI, SD and rates of DSM-5 Insomnia Disorder on average. However, secondary measures such as SRI, TST, SOL and WASO did not have meaningful differences. Spina et al. (2023) interpret the results as saying that: providing feedback and guidance did not alter sleep perception and SWSD more than sleep education and hygiene. This surprisingly opposes prior preliminary findings that suggest otherwise (Bensen-Boakes et al., 2022). However, there are limitations to the study. The researchers mention a few limitations that could not be avoided but were considered. The sample cannot be generalized to individuals with physiologically based sleep disorders or severe health conditions. The sample taken was predominantly white, working full-time, and in a relationship, which limited samples. Occasional missing data was also a concern, as there were only two check-in calls given for the participants to troubleshoot their devices. Finally, the study did not explore individual differences in response to the intervention, making it possible that some members did benefit from the intervention due to uncontrolled alternate factors. Understanding how the data relates to other outside stressors and if the intervention could benefit greater with slight alterations requires further research (ibid).

There are also other limitations that may not have been as significantly considered. The study was single-blind, meaning there may have been unconscious bias from the participants whilst taking part, causing a response that may have contributed to certain results having an insignificant difference, or causing them to alter their lifestyle habits due to unconscious bias based on group assignment. Questions were slightly leading, with phrasing like “At this point, how successful do you think this program will be at enhancing your sleep?” and “By the end of the program, how much enhancement in your sleep quality do you think will occur?”, potentially leading to a placebo effect that may cause participants to believe that the program will certainly improve their sleep quality, or the opposite. The study was also marketed as the “Novel Insomnia Treatment Experiment”, which may have further added to unconscious bias from the participants.

However, the study does have some practical applications. While the effects of using feedback and guidance via wearable devices alone seems likely to not better than the benefits of CBT, there may be some benefit in combining the two approaches, especially since an increasing number of individuals come to clinics with their own recorded sleep data, and expect that clinicians will use that data to aid them (Spina et al., 2023). Sleep diaries are also present as a core component of CBT (ibid), and applying sensor-reported data to the customary practice of sleep diaries in CBT may help the clinicians in determining the best and most effective course of treatment, giving tangible data they can use to check progression of insomnia symptoms. Overall, there is some validity to the conclusion presented by Spina et al. (2023), however, much more research is required to indicate if this is a viable treatment, especially with larger, more diverse samples and outside stressors, and if this can be used alongside current treatments like CBT.

References

Bensen-Boakes, D.-B., Lovato, N., Meaklim, H., Bei, B. and Scott, H. (2022). ‘Sleep-wake state discrepancy’: toward a common understanding and standardized nomenclature. SLEEP, 45(10). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsac187.

Berryhill, S., Morton, C.J., Dean, A., Berryhill, A., Provencio-Dean, N., Patel, S.I., Estep, L., Combs, D., Mashaqi, S., Gerald, L.B., Krishnan, J.A. and Parthasarathy, S. (2020). Effect of Wearables on Sleep in Healthy individuals: a Randomized Crossover Trial and Validation Study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 16(5), pp.775–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8356.

NHS (2024). Insomnia. [online] NHS. Available at:https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/insomnia/.

Shrivastava, D., Jung, S., Saadat, M., Sirohi, R. and Crewson, K. (2014). How to interpret the results of a sleep study. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, [online] 4(5), p.24983. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v4.24983.

Spina, M.-A., Andrillon, T., Quin, N., Wiley, J.F., Rajaratnam, S.M.W. and Bei, B. (2023). Does Providing Feedback and Guidance on Sleep Perceptions using Sleep Wearables improve Insomnia? Findings from ‘Novel Insomnia Treatment Experiment’: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Sleep, 46(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsad167.

Like this project

Posted May 21, 2025

Study on wearable devices' impact on insomnia management.

Likes

0

Views

4

Timeline

Oct 24, 2024 - Nov 23, 2024