How Ice Skating Made Fifth Avenue a Fashionable Destination

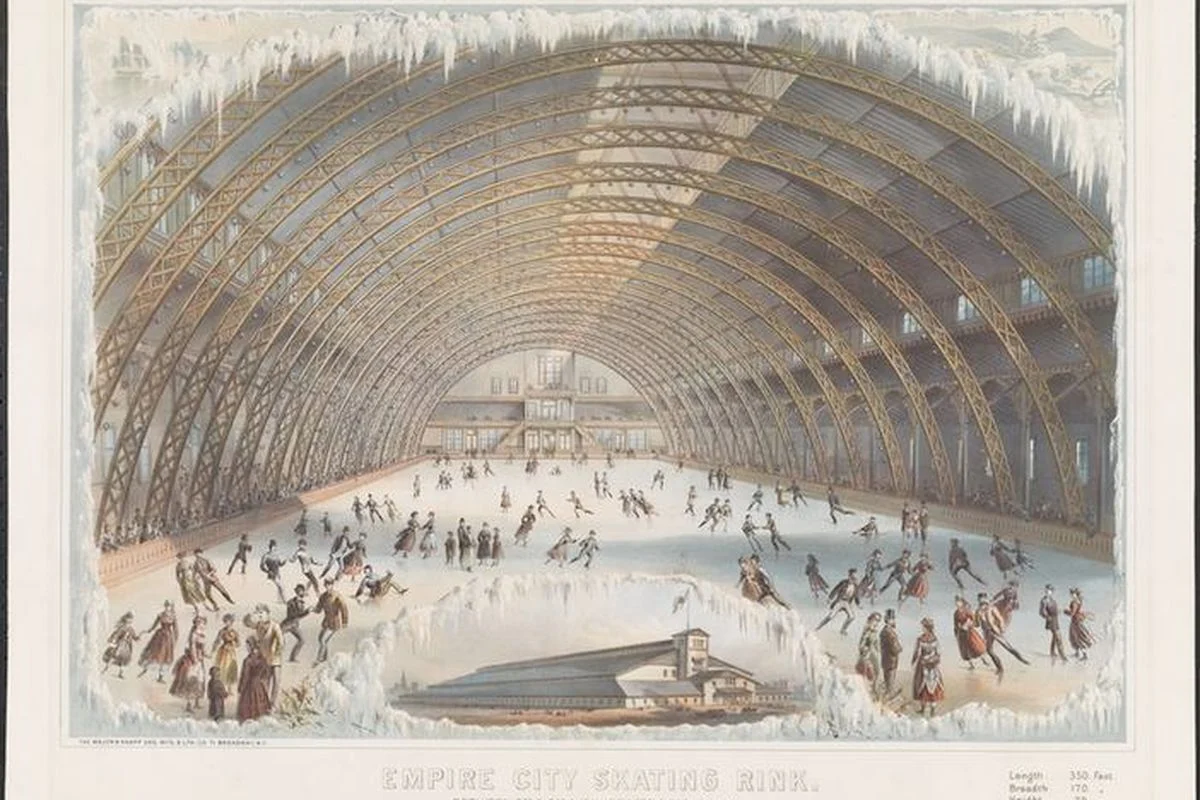

The Empire City Skating Rink. Major & Knapp Engraving, Manufacturing & Lithographic Co. (New York, NY). /

When Central Park opened, upper Fifth Avenue was rural and remote. Ponds and streams dotted the area around 59th Street. Unpaved roads were lined with cattle yards and stables. Saks was far in the future. Yet fashionable New Yorkers still trekked north from Washington Square—to go ice skating.

In the 1860s, when the neighborhood tipped from sylvan to stylish, private skating ponds led the charge. They lured the elite with costume balls, fireworks, music, spacious restaurants, and selective membership. Two ponds were located across the street from one another at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, where the Plaza Hotel and Apple Store now stand, and another at 46th and Fifth, now a Guess store. Skating there was the highlight of the winter social season.

Central Park spurred this transition, drawing the masses to the city's outskirts. It was a hike for most residents, who lived below Madison Square, but was reachable by carriage or by the horse railway cars on Third or Eighth avenues. One of the first parts of the park to open to the public was the skating pond, now called the lake, in the winter of 1858-1859. The pond kicked off a skating mania. New Yorkers had practically forgotten the sport, since the downtown ponds that had once been used for skating, like the Collect Pond, had long been built over. Central Park, as intended, reintroduced residents to such fresh-air pursuits. Within a few years, three more park ponds were opened for skating.

Park commissioners waited to open the ponds to skating until there were four or five inches of ice, which held thousands of skaters at a time. Once it was deemed safe, they raised a red ball by the bell tower just south of the reservoir. "The ball is up" became the universal code for a skating day and the words created a frenzy. "The city railroad cars would have deceived any stranger to the city," the Herald reported about a freezing cold day in 1860, "and made him believe the Japanese had returned to New York, for at the end of each vehicle was a flag, with a flaming red ball on a white ground." Some cars were even said to fly this flag falsely in order to attract customers.

The skating pond was surrounded by buildings for renting skates or warming up by a fire. The "rude but comfortable" Casino, on the southern shore, served beer, cream soda, and hot chocolate. For 25 cents or less, hungry skaters could order fried oysters, pickled tongue, chowder, sandwiches, or cakes. The Casino and the saloon at the lower lake were run by Charles A. Stetson, owner of the Astor House, a luxury hotel. Yet unlike that exclusive downtown spot, the park restaurants catered to a wide range of New Yorkers. Visitors to the skating pond were of "all ages, sexes and conditions of life, from the ragged urchin with one broken skate, to the millionaire in his richly-robed carriage," said the Times. Scots held curling matches on the lower pond. Workers from Ireland and Germany thronged the ice on Sundays.

Ladies were the main attraction of the skating ponds. At first, they had their own enclosure in Central Park, but it didn't last long. For many women, the whole point was to show off to the men and skate together. Ice skating was one of the only activities that single men and women could do together unchaperoned. At the park, wrote the Times, "it was a common sight to see a gentleman with two pairs of skates on one arm and a bundle of crinoline on the other." Skating also conveniently drew couples close together on moonlit nights. "The habit of depending upon gentlemen for support is a most pernicious one," a contemporary observed, but it was hard for learners to avoid. Men were often treated to the flash of an ankle or even—oh sweet lord—the chance to tie a woman's skates and get "the faintest peep of the hem of a Balmoral," an undergarment. Fit and attractive, the women made prime wife material. "Many a young fellow has lost his heart, and skated himself into matrimony, on the Central Park pond," said an 1866 guidebook.

Reporters panted over the sight of "pretty girls, prettier legs, the prettiest feet" on the ponds. But women were more than just eye candy. They were talented skaters who thrilled in the sport. It was a liberating escape from the stultifying ballroom, the cold be damned. Contemporary observers welcomed it as an invigorating new amusement that gave women strength and energy (plus a healthful glow in the cheeks).

Women made ice skating fashionable. But Central Park was too crowded for patrician sensibilities and soon enough the upper class got its own private pond. In 1862, Major Oscar Oatman—who ran Park Slope's high-end Washington Skating Club—opened the Fifth Avenue Pond, the first private pond in Manhattan. It was, the Herald said, "the resort of the higher classes, who desire to be select in their skating as in everything else."

The Fifth Avenue Pond was naturally formed, one of several in the vicinity, and fed by a spring. For years boys had skated on these ponds, especially those on the Beekman estate around 61st Street between Fourth (now Park) and Fifth avenues. Like Beekman's, the Fifth Avenue Pond was located in a hollow that sheltered it from the wind. Covering an area of 11 acres, it sat between 59th and 57th streets and Fourth and Fifth avenues. Madison Avenue originally ended at 42nd Street and apparently didn't cut through the pond for a few years; the first mention of it affecting the pond was in the Tribune in 1865. The article said that its dimensions had been curtailed that summer, as "the inexorable hand of improvement…[pushed] a raised thoroughfare almost through its center." But the shrunken pond stayed open until at least 1868.

Oatman fenced the area and erected buildings for a cloakroom and a saloon with warming stoves. He was a constant, genial presence at the pond, attending to every detail. The ice was kept "clean as a parlor," with workers quickly sweeping up snow and cigar stumps. Women and children could take lessons, while those unable to skate could be pushed in chairs with gliders. At night, calcium lights (also called limelights) and large reflectors illuminated the pond. Every afternoon, a brass band played "a variety of national and operatic selections." This could be a challenge in the cold. Even when the city experienced record, below-zero temperatures in January 1866, the musicians blew on through chattering teeth.

Most importantly, Oatman only admitted members of "character and respectability," who could produce quality references and pay $10 for a season pass, more than most New Yorkers made in a week. The pond opened as early as 7 a.m., since "fashionables are in the habit of skating before breakfast," and shut at midnight. It was closed on Sundays, which was then considered in good taste. It also happened to be the only day most people had off.

The patrons at the Fifth Avenue Pond looked sharp on the ice. They wore beribboned caps, Highland plaids, fur muffs, and custom skates costing up to $50 (some $700 today). Bright colors prevailed, with dark hues deemed too gloomy for the merry scene. Dresses were "short," just above the ankle. Men wore chinchilla pea coats and Scottish wool trousers. Each season, Harper's Bazaar made detailed recommendations for fashionable skating dress: fur-trimmed Russian suits, plumed seal-skin toquet hats, jaunty short jackets, or calf-skin skates with chamois lining. It advised against white undergarments while skating, preferring blue merino stockings. As for a lady's hair, "elaborate coiffures are in bad taste in the half undress of the skating costume," it said in 1869. Better: "A braided chignon with a crimped tress is not too dressy."

The highlights of the season were the skating carnivals, or costume balls on the ice, a spectacle "rarely if ever before seen out of Russia." The events drew carriage after carriage of patrons and featured costumed skaters, ice-dancing, and fireworks. At one ball in January 1865, the Tribune reported, some skaters wore grotesque masks or dressed as Seneca Indians. Others came as Zouave officers, a brightly-attired regiment in the Civil War, which was still being fought a world away from Fifth Avenue. People gathered outside the pond to look down at the spectacle: "There you beheld a beautiful girl, with a jockey hat and rooster feather, executing, in wonderful style, a charming pas de deux with a fur-clad gentleman…Now half a dozen young men come flying along with Roman candles in their hands…some have lanterns on their ankles, and glide by like fireflies in the summer night."

Oatman also hosted ladies' skating matches, cannily capitalizing on his pond's primary draw. The "novel contest" drew crowds to the surrounding banks to watch women compete for a solid gold medal. At a match in February 1868, the Evening Post reported, spectators comprised "ladies and gentlemen belonging to the highest circles of society in this city." After announcing a winner, "Major Oatman, with his usual liberality, gave notice that each of her competitors would also receive a gold medal," handed out like Little League trophies.

The judges of the contests were members of the New York Stating Club. Founded in 1863, the club was headquartered at the Fifth Avenue Pond from 1865 until 1868. These so-called "fancy skaters" had their own clubhouse on the property and put on a constant show at the pond. "Many of the members," the Herald said, "are perfect masters of the art of skating, and their graceful motions on the ice never fail to excite the admiration of all visitors to this uptown resort." These included E.B. Cook, the club meteorologist and expert in the form, and Alexander McMillan, a champion skater who also manufactured ice skates. McMillan even designed a "New York Club Skate," a pricey model made of solid steel and iron.

The club moved across Fifth Avenue in 1868, probably due to the closure of Oatman's pond. That year, Mary Mason Jones began building a chateau-style marble mansion (right, via MCNY) on Fifth Avenue between 57th and 58th Streets. An old-money matriarch and aunt of Edith Wharton, Jones also erected matching houses on the block, known collectively as "marble row." Its construction signaled the end of bucolic midtown and likely squeezed out the Fifth Avenue Pond. The other ponds soon followed.

In a thinly-veiled portrait of Jones in The Age of Innocence, Wharton describes her aunt's "geographic isolation." The character Manson Mingott would "sit in a window of her sitting-room on the ground floor, as if watching calmly for life and fashion to flow northward to her solitary doors." In reality, the area was not quite so dull. St. Patrick's Cathedral slowly rose on 50th Street and a few other pioneers built homes nearby. Jones would have spied activity kitty-corner to her property, at Mitchell's Pond, which next hosted the New York Stating Club. Located at the current site of the Plaza Hotel, it had similar amenities to Oatman's, with skating contests, live music, and polka-dancing on ice.

After Mitchell's closed, the club briefly moved to McMillan's Pond at 46th Street and Fifth Avenue, run by one of its own members. Surrounded by elegant mansions, it replaced the Fifth Avenue Pond as a gathering spot for the elite. On a Christmastime visit in 1870, a sports magazine observed that "so many people representing many of the leading families in the city were never seen on a skating pond before. This cozy little pond—the ice of which is in excellent skating order—is peculiarly adapted to the convenience of the ostentatious specimens of humanity in which New York abounds." Perhaps even Mary Mason Jones deigned to visit.

This party too was short-lived, as development plowed northward. Soon artificial rinks replaced natural ponds. New Yorkers could now skate protected from the elements at the likes of the Empire City Skating Rink at 63rd Street and Third Avenue, which opened in 1868. The size of a football field, it had a 70-foot-high arched ceiling, hundreds of gas lights, and commodious refreshment rooms—modernity incarnate. Thirty years later, when John D. Rockefeller wanted a private pond for skating, he simply made one, pouring water onto a shallow slab of concrete. Built on his 54th Street property, it was, according to the Times, "probably the costliest ice in the world."

McMillan's Pond was paved over in 1871 to build the Windsor Hotel. Grand Central Depot had just opened on 42nd Street and travelers needed a place to stay nearby. The lavish seven-story hotel had cutting-edge amenities like elevators and a stunning 139 bathrooms. It marked an encroachment on "the privacy and exclusiveness of Fifth Avenue," the Times said in 1873, catering instead to a transient public. Eventually hotels occupied the land that had been Mitchell's and the Fifth Avenue Pond's, too, their spirit echoing only in the fur hats and exclusive air.

But the new Fifth Avenue hasn't entirely neglected its winter legacy. Rockefeller Center's rink is just a few blocks away from the old McMillan's Pond. The newer one could be described as the older one was, as a place where "the passers-by on three different sides can stand and look down upon the moving human figures." Gawking and exhibitionism remain central to the sport's urban allure. Only today, skaters come to upper Fifth Avenue not to escape the city, but to be in the thick of it.

Like this project

Posted Feb 22, 2024

I conducted original research on ice skating in 19th century NYC. I consulted archives, historic images, and contemporary newspapers, and wrote a long story.