Audience and Community: journalists must focus on the latter

Something that my high school journalism teacher always said has stuck with me to this day: journalism is about creating an informed community.

When I first started, that meant informing the students at the school about dances and events, football wins and tennis losses. It didn’t mean much to me because I didn’t put much stock into the idea of “community” at a high school of nearly 3,000 students. I barely knew 50% of my class.

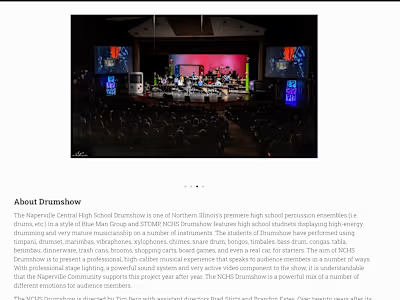

By the time I was a senior in high school, however, the tone of my teacher’s message changed. The Naperville Sun had been bought out by Tribune Publishing in a huge deal that included many suburban newspapers formerly owned by the Sun-Times.

The turnover was rough; people in my town weren’t sure where to get their news anymore. My journalism teacher encouraged us to chase this opportunity and try and fill in the gap. Even without a strong newspaper, the people in Naperville still needed news, and our high school newspaper had the chance to give it to them.

In the end, our small staff of 20 high school students wasn’t able to meet that need, but that experience of striving for more and trying to give our community what they desperately needed always stuck with me. It lingered in the back of my head. It was a regret, something I wished we pulled off.

It wasn’t until later, when I got a chance to talk to Terry Parris, Jr., Engagement Editor at The City, that I realized what we had been doing wrong. We wanted to write for the community, but we never stopped to ask what they wanted to read.

As journalists, we often talk about our audience. Who is our audience? Will they be interested in this story? How can we make them interested in this story? Parris, however, offered a reframe of this idea: the audience will always be there. They are the people who read the paper every day and have the time and privilege to be able to afford that. They aren’t going anywhere.

However, the stories should be about communities. They can be something as small as a 300-word brief on a fallen street sign to long investigations of housing insecurity in a specific neighborhood. These stories are meant to enlighten the community, to help them understand what is going on around them and make informed decisions. To be able to do this, reporters have to actually talk to the community.

The City is helping set the tone for how community engagement, especially in local journalism, will have to function moving forward. Partnering with the Brooklyn Public Library, they have a program called Open Newsroom, where they encourage community members to engage with reporters and let them know what they want to read.

In our own city, City Bureau is striving for the same things through their Public Newsroom events. These events are meant to build trust between the newsroom and the community and help shape the way they report on issues that community members and stakeholders say are important.

Being able to tell the difference between audience and community is important. Focusing too heavily on the audience has ended up privileging those who have the means and access to read the newspaper every day and buy a subscription. These people are often wealthier, white and have the time to spend on reading the paper.

According to a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center, only 64% of adults who consume local news in the Chicago area said that local news was in touch with the community. Only 17% said they had spoken with a local journalist.

This reflects a necessary way for local news to grow in the Chicago area, according to another study by Pew. The issue with the changing media landscape is not video and multimedia, or the transition to digital media. Most Americans are fine with digital media to get their news, and will remain engaged with it. However, what they desire is a strong community connection.

If I could go back to high school and redo that senior year when I was on our managing staff, I would have done things differently. I would have invited the community in and asked them what they wanted to read. I would have created a discursive process that would allow journalists and community stakeholders to discuss what people need to know more about. I would have focused on the stories that would make the greatest impact for the people reading, rather than just the stories I was interested in.

It’s too late now for me to go back to that high school newspaper. All I can do is carry these lessons forward.

Fake news, media bias and out-of-touch reporting; with the increasingly divisive political climate shaking up the way we cover politics, ethical debates about covering elections and political bias are more relevant than ever.

Many hard-nosed political reporters don’t vote; some, like Peter Baker of the New York Times have openly said that they don’t vote, don’t belong to non-journalism organizations, don’t belong to political parties and don’t even voice opinions on political issues in private.

For New York Times reporter Astead Herndon, the debate is much more nuanced than just a blanket ban.

“I don’t think there’s a hard and fast rule for folks,” Herndon said. “I think that you should do the things that you feel comfortable with and not think that things like voting in a political election makes you less biased, more biased, unless it does.”

It’s a matter of introspection. Without the understanding of what makes one biased personally, it is irrelevant to talk about issues of voting or not voting, he noted.

“I think that the question of voting is small potatoes,” Herndon said. “There’s a more important thing which is about maintaining a journalism that is more than just performatively objective, but fair.”

Herndon has spent much of last year covering the presidential election and will continue to do so until the general election this November. Much of his coverage has discussed black voters, and he hopes to give black voters more well-rounded coverage moving forward.

“I try to take it as, ‘if you’re just writing about the group writ large, you’re probably not showing the necessary nuance between them,” Herndon said. “It shouldn’t be a story about black voters by itself, but generational differences or ideological differences between them.”

Political journalism has always been flawed, Herndon says, and all election coverage has good and bad sides. He says that the only way to provide fair coverage is to actually talk to voters.

“I think that all presidential elections involve good and bad journalism,” Herndon said. “I think that one of the things that we’ve tried to make the priority here is to get out on the road and to make sure that we’re not just embedded with the campaigns themselves, but also (in) the kind of communities which decide our elections.”

One major criticism of political journalism is that it focuses too much on the politicians and not enough on the other stakeholders in our political climate. According to Jonathan Stray in a Medium article, many people who grew up with the internet—people who are now considered a part of the group vaguely termed “young voters”—have become disillusioned with the horse-race style of covering politics, and want to see more of the community and society as a whole reflected in political coverage.

Stray brings up the example of the push for gay marriage, which largely took place in the courts between community activists and stakeholders. Political coverage that focuses entirely on politicians would have missed most, if not all, of that story.

Herndon agrees that political coverage, especially in elections, could benefit from more focus on the people who aren’t in the public eye to better understand the political climate as a whole, rather than just the piecemeal understanding that comes from being a part of a campaign.

“[Reporters should] reflect the kind of diversity of the electorate,” Herndon said. “It has been a real priority for not just dealing with the kind of same constituencies that we’re used to, but making sure that the breadth of, in this primary, the Democratic voters that are electing our representatives. That includes black voters, Latino voters, old and young and kind of the nuance between them.”

This point of view reflects the ever-changing political discourse around voting, voter turnout and issues like voter suppression. Without information from the community, it is difficult to say with any certainty what is actually happening at the ground-level. On top of this, readers are no longer getting their information in the same way they did 20 years ago; and those pathways are constantly shifting and merging.

“I think you have to be comfortable with change,” Herndon said. “I think you have to understand the ways in which people get their information has changed. And you have to understand that voters aren’t necessarily coming from things from the same lens in which you are.”

In the end, Herndon’s coverage is about making sure that he is talking to people on the ground, understanding where they’re coming from and where they’re going, fully immersing himself in a community and reflecting how their getting their information and how they’re using it.

“I should know kind of the different media ecosystems in which Democratic voters are [getting information],” Herndon said. “I should know the regional differences between the communities and try to reflect that. That’s just how the job should be done.”

For Herndon, however, this doesn’t mean fundamentally changing our reporting, just the tools journalists use to cover politics.

“I think that the same tenets of the profession hold true,” Herndon said. “It’s just the tools that you’d have to use to be able to execute [good journalism] change.”

-30-

By Bianca Cseke

Sandhya Kambhampati knows a thing or two about data journalism.

As a reporter on the Los Angeles Times’ data desk, she covers everything from elections to demographics and how natural disasters affect tourism in small California towns. When she was with Propublica Illinois, Kambhampati helped with an investigation on the Cook County property tax assessment system, a piece that was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2018.

But even though nearly all of Kambhampati’s work uses data and public records to get vital information to the public, she never forgets about the people who her stories impact.

“People are always at stake,” she said. “You always want to go back to the people whose lives and livelihoods are impacted.”

For example, the property tax assessment story Kambhampati worked on started with a tip Jason Grotto, the other Propublica reporter she worked with on the story, received from a real person — not from digging through sets of data on a fishing expedition. The reporters also told the stories of people impacted by property tax assessments favoring pricier commercial buildings at the expense of the owners of cheaper ones.

That included Brenda and Larry Doyle, a couple who own a daycare in Chicago’s West Auburn Gresham neighborhood. Their business’s property value was assessed higher than what they had actually paid for it and that value never went down, while a nearby larger, more expensive building kept getting lower assessments.

When asked what a journalism student who’s about to graduate should know about data reporting, Kambhampati said what reporters from every area of journalism have given as advice: Understand how to write a story and how to conduct an interview.

While it can be useful — even vital — to know how to clean data so it can be understandable for reporters and the general population, once that part of the job is done, even a data reporter needs to be able to think in terms of old-fashioned, basic reporting.

“The way you interview people, you want to interview your data,” Kambhampati said.

That means that when a reporter looks at a set of data, they should ask “the same fundamental questions,” such as why the data says something, who is responsible for it and who it affects, how it came to be and what it is truly saying in the first place.

And no matter how much a data journalist immerses themselves in numbers, they should still remember to always include the people affected by the story.

“Don’t bog the story down with too many numbers,” Kambhampati said.

Other than that, aspiring data journalists should remember to send out records requests early on in the reporting process rather than waiting until later, she said. You never know when officials will put up a fight in getting a reporter the information they need.

Plus, that data can take a lot of work to clean up.

“That’s the thing about data: It might be clean in the heads of the people who put it together, but it might not be for everyone else,” Kambhampati said.

By never forgetting about why most journalists do the work they do — to help people — Sandhya Kambhampati has managed to produce work that has made a difference beyond just the awards her work has garnered or been a finalist for, like when she was part of a team that investigated the German nursing home system. That investigation brought about discussion across Germany about how its nursing homes should be evaluated. By following some of Kambhampati’s advice and working to produce journalism that makes a difference, journalists can help change lives for the better.

-30-

Like this project

Posted May 19, 2023

Wrote and edited a blog post for DePaul University's Center for Journalism Integrity and Excellence

Likes

0

Views

2