London’s Great Stink

From HeinOnline’s

.

The Great Stink

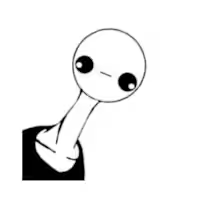

Even though officially John Snow’s conclusion that cholera was caused by drinking fecal-contaminated water had been rejected, cholera remained a public health enemy. London continued to try and rid the city of cholera-causing smells. The “solution” continued to be to empty sewers into the Thames.

Almost since its inception, various proposals had been made to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers and its successor, the Metropolitan Board of Works, to build new sewers and pumping stations. They were all rejected for being too costly.

But four years after the Soho cholera outbreak, London’s sewer struggles were becoming unignorable from an olfactory point of view. The flushable toilet had been invented and subsequently increased the amount of wastewater being emptied directly into the Thames. The city’s sanitation work had transformed the Thames itself into one giant cesspit.

Summer, 1858: Sewage Is in the Air

In the summer of 1858, London sweltered under an oppressive, record-breaking heatwave, which baked the putrid river and intensified its already horrible stench. As summer blazed on, the Thames’ water level dropped, exposing liquid sewage caked into the river’s banks. Rich or poor, noble or common, no one was immune from the great stink.

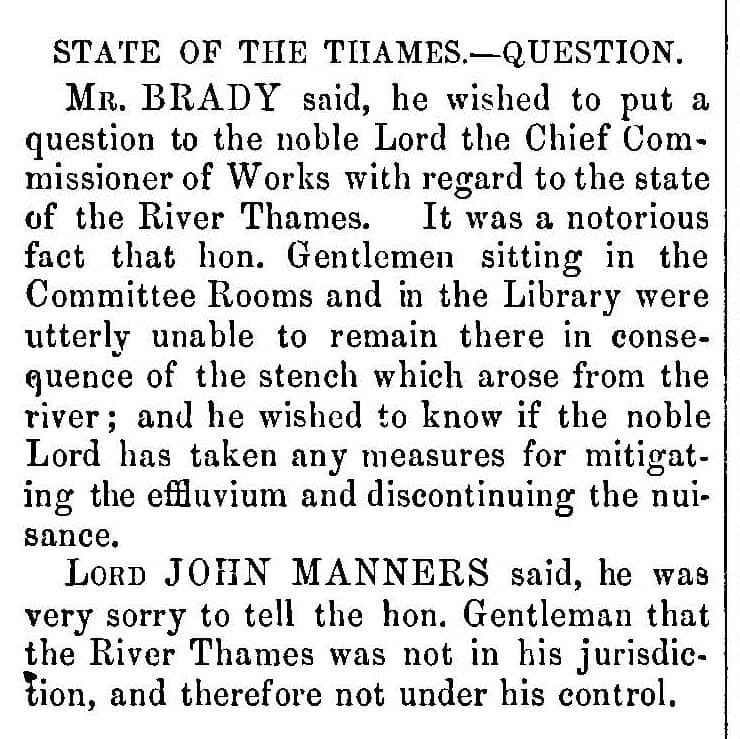

Even Parliament, sitting next to the polluted river, wasn’t shielded from the stinky suffering. The first whiff of how bad the situation had become came on June 4th, when MP Griffith asked Lord John Manners, Chief Commissioner of Works, about “the effect upon the purity of the air which may be produced by the liberation of gases injurious to health from the water.” Nothing was done. On June 11, MP James Brady rose to again question Lord John Manners about the smell, which made sitting in the committee rooms and library impossible, asking if “any measure for mitigating the effluvium and discontinuing the nuisance” had been made. In response, Lord John Manners informed him that the River Thames was not in his jurisdiction.

Found in HeinOnline’s

.

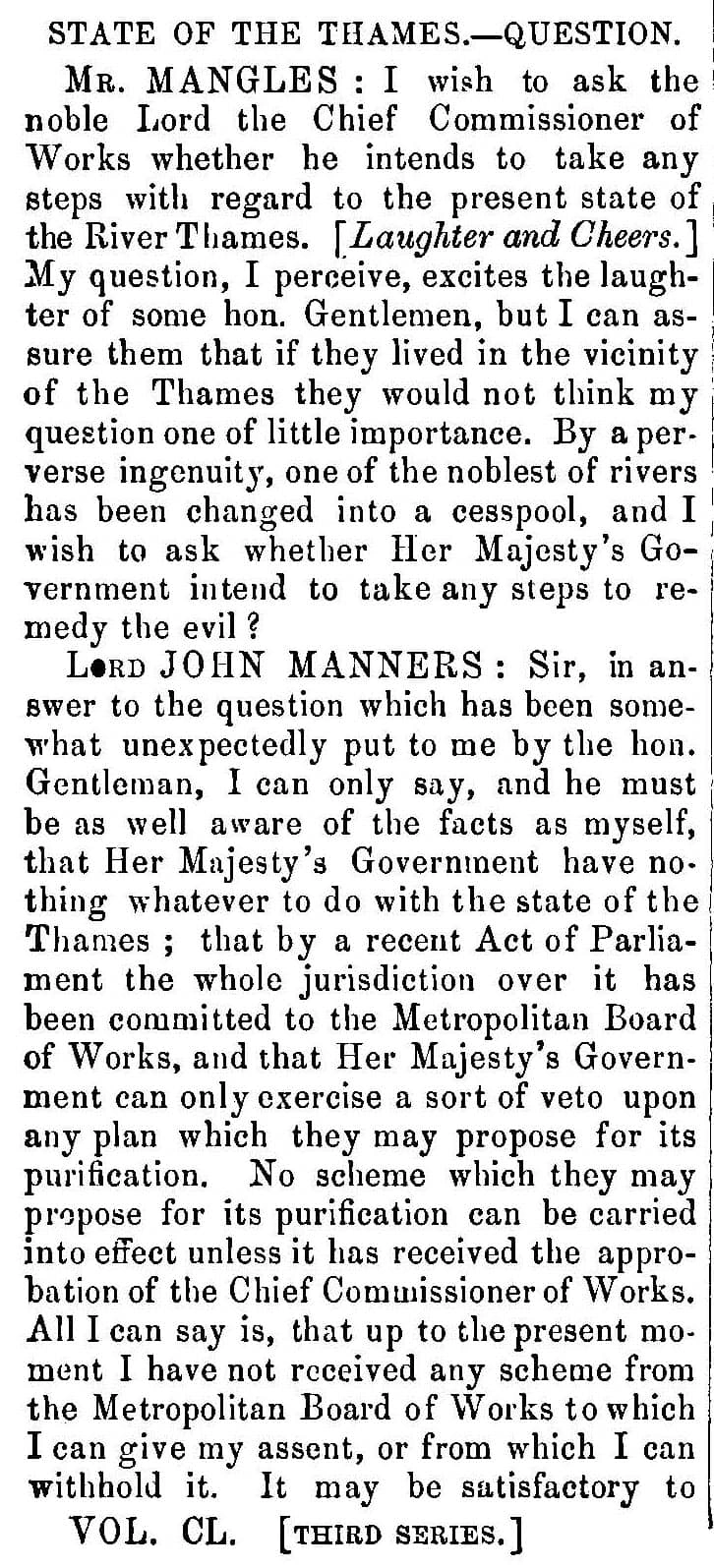

On June 15, Lord John Manners was once again grilled about the river’s state, this time by MP Ross Mangles, eliciting laughter from some of his fellow MPs. “My question, I perceive, excites the laughter of some hon.(orable) Gentlemen,” Mangles said, “but I can assure them that if they lived in the vicinity of the Thames they would not think my question one of little importance.” He went on to describe the situation as one where “by a perverse ingenuity, one of the noblest of rivers has been changed into a cesspool.” Again, Lord Manners replied that “Her Majesty’s Government have nothing whatever to do with the state of Thames” and that the matter fell squarely to the Metropolitan Board of Works.

Found in HeinOnline’s

.

To help mitigate Parliament’s suffering, the building’s windows were covered in curtains soaked in chloride of lime. It didn’t work. On June 25th, the Thames’ stinky state earned protracted debate in the House of Commons, after various attempts to better ventilate the chamber had failed. The Courts of Exchequer and Queen’s Bench had also been infected by the “pestiferous invader” and had been adjourned, unable to work through the great stink.

Bazalgette Freshens up the Great Stink

Working with a speed that was no doubt spurred to ameliorate their own suffering, on July 15th the House of Commons cleared its docket to hear the Metropolis Local Management Amendment Bill, which would write a check to the Metropolitan Board of Works for whatever it would cost to achieve “the purification of the river Thames.” Chancellor of the Exchequer (and future Prime Minister) Benjamin Disraeli prefaced his reading of the bill by commenting:

The bill was passed on August 2nd.

The ultimate solution to the Thames’ woes had been floating around since 1856, when Joseph Bazalgette was elected Engineer to the Metropolitan Board of Works. At the time, Bazalgette proposed installing more than 1,000 miles of new street sewers. It was rejected then for being too costly. Now, repulsed by the smell of inaction, Bazalgette was given the funds to completely rebuild London’s sewers.

Bazalgette’s sewer system has been called “the most perfect, the most comprehensive, and at the same time the most difficult work of its class that has ever been executed.” Ornate and opulent pumping stations moved sewage down the Thames and out to sea. Bazalgette’s sewers took almost 20 years to complete and for his services to the city, Bazalgette was knighted in 1874. Bazalgette’s sewer system still services London today, although, in a callback to history, modern life has strained the system’s capabilities.

Smell History with UK Parliamentary & Government Publications

This exploration of the Great Stink wafted across the internet with generous reliance on one of HeinOnline’s newest products, UK Parliamentary & Government Publications (Public Information Online), a partnership with Dandy Booksellers that brings millions of pages of key UK parliamentary materials into HeinOnline. This resource offers more than just a database; it’s a historical record, a research tool, and a legislative library all in one—and can be used to research just about anything that happened in British history, even great stinky summers. Curious what corners of history you could sniff out with this resource? Click the buttons below for more information.

Like this project

Posted Aug 15, 2024

London, 1858. Citizens suffer through a very disgusting, very smelly summer that, almost 170 years later, is still ominously remembered as the Great Stink.

Likes

0

Views

9