Native Speakerism: Discriminatory Practice or Response to Marke…

native-sp3 (1)

English has become the world’s first truly global language. It is the global lingua franca for business, diplomacy, and tourism; it is the unofficial first language of the Internet; and its use, thanks in great measure to the ELT industry, is growing daily. There was a time when learning English from a so-called NEST (Native English-Speaking Teacher) was the indisputable standard and sitting in a classroom with an NNEST (Non-Native English-Speaking Teacher) in charge was considered less than ideal.

Times have changed and, with them, opinions on what makes a good ESL teacher beyond their status as either NESTs or NNESTs. Since Péter Medgyes first opened the subject up for debate in 1994 in his book, The Non-Native Teacher, a growing number of academics have researched the topic of Native Speakerism in the teaching of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) around the world, and several have concluded that this preference for hiring native English-speaking teachers is at best a discriminatory practice and at worst “neo-racist.” Despite this, it is still common to find ESL job advertisements for teachers requesting applications only from native speakers. This occurs regardless of the fact that, in the European Union, for example, it is illegal to advertise jobs only for native speakers of any specific language under non-discrimination law. Other regions and countries regularly advertise for both native-speaking teachers and non-native teachers but then offer much lower salaries to the non-natives.

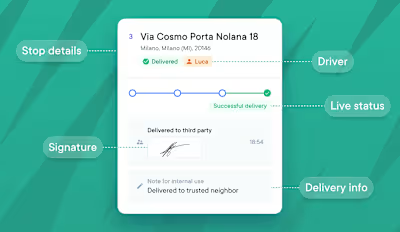

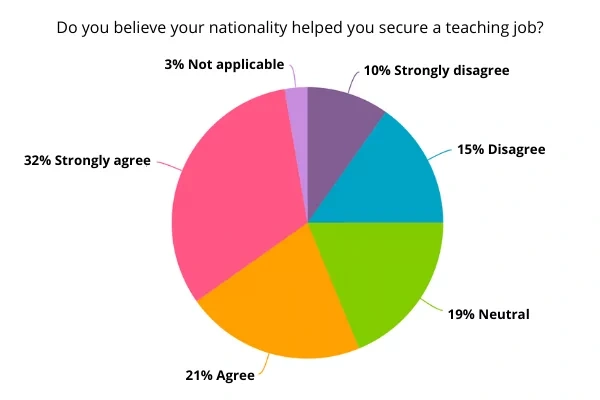

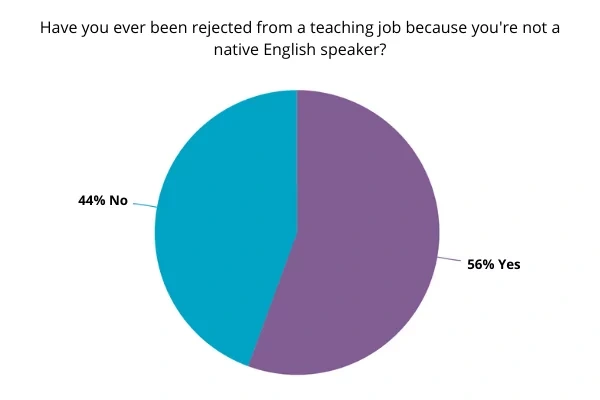

In a recent survey by Bridge Education Group of over 500 teachers that have graduated from a Bridge course or are currently enrolled in one, 53% of teachers who come from native English-speaking countries responded that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their nationality helped them secure an ESL teaching job (figure 1), while 56% of NNESTs reported being actively rejected from a job because they are not native speakers (figure 2), and 35% felt discriminated against for their nationality while teaching (figure 3).

BridgeUniverse spoke to academics, NESTs, NNESTs, and teachers who object to any such classification, as well as anti-Native Speakerism advocates, teachers struggling to be identified as native speakers, and owners of ESL schools and academies across the world in an attempt to get a picture of the current state of the Native Speakerism debate and its reality.

Figure 1: Survey to native English-speaking teachers.

Figure 2: Survey to non-native English-speaking teachers.

Figure 3: Survey to non-native English-speaking teachers.

Potential pros and cons of NESTs and NNESTs

The launch of the debate on Native Speakerism was quickly followed by a host of voices advocating for NNESTs to be hired on the same basis as NESTs and even a focus on the benefits of hiring non-native English-speaking teachers over their NEST counterparts.

The counterargument is that native speakers have an intuitive grasp of the language that a non-native speaker may never be able to achieve. As Douglas, a teacher at a British school in Eastern Europe, puts it, “I’m not sure a non-native could have the same enthusiasm for the language. Nuances [such as] idioms, phrasal verbs and all these things that a native doesn’t even have to think about and the subtle difference between meanings of words […] It’s very important for students of English to spend time with native speakers, to hear the cadence, the correct orders, and the fixed pronunciations of the language.” Douglas acknowledges, however, that “there are many fantastic non-native teachers out there, for sure,” and that the quality of both natives and non-natives also heavily depends on the resources and support provided by the schools themselves.

Marek Kiczkowiak, founder of TEFL Equity Advocates, an organization set up to tackle Native Speakerism and help NNESTs find work, in a recent interview for BridgeUniverse, disagrees with the view that NESTs provide better models for students: “Apart from the bias in recruitment, Native Speakerism leads to many other biases. For instance, there is this idea that ‘native speakers’ are better pronunciation models, which of course influences how we teach English.”

The idea that native speakers can also provide input to students about native cultural contexts is also countered by teacher, educator, and writer Scott Thornbury. “The argument for the teacher as the personification of cultural values no longer applies with English – not just because of its international language status – but because even in English-speaking contexts there is no homogeneous culture, or at least there is no teacher who can claim familiarity with all the different English-speaking cultures that exist.” Thornbury also believes that, “For many learners, English is a global language and not one that is geographically or culturally situated, [and this] has moved the goalposts significantly – even if not all learners (or, indeed, all teachers) have realized it.”

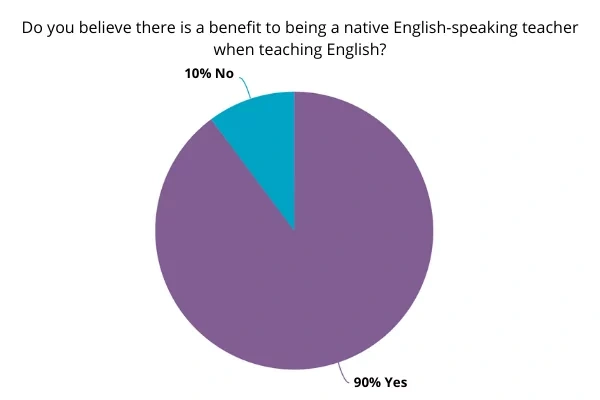

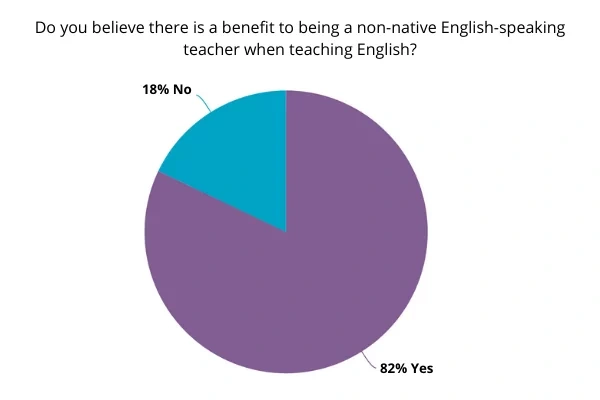

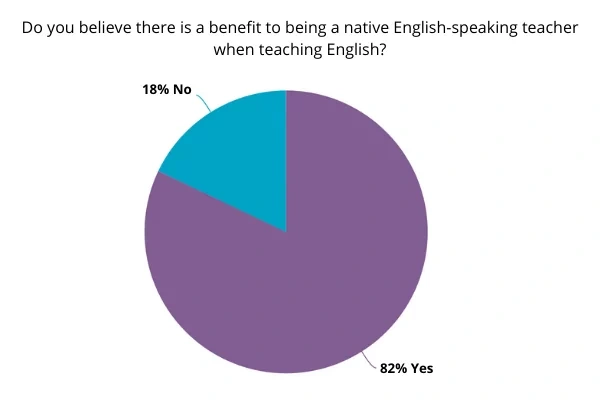

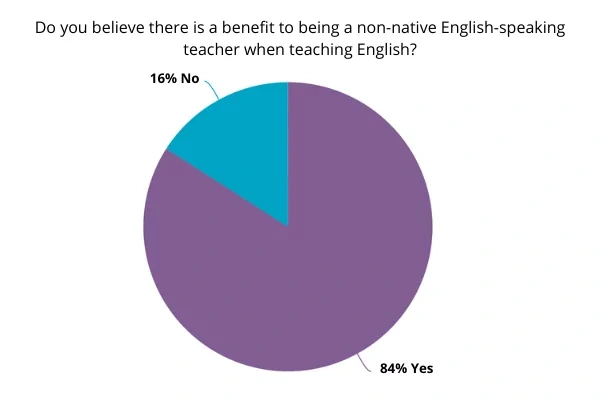

Bridge’s Native Speakerism survey found that 90% of NEST respondents “believe there is a benefit to being a native English-speaking teacher when teaching English” (figure 4), but 82% of those same teachers also believe “there are benefits that come with being a non-native English-speaking teacher” (figure 5). The latter belief is also backed up by their NNEST counterparts, with 82% believing there is a benefit to being a native English-speaking teacher (figure 6) and, at the same time, 84% agreeing that there is also a benefit to being an NNEST (figure 7). These findings clearly suggest that each group has its benefits, but likely in different areas and for different reasons, and that each category has something unique to offer in the ESL classroom.

“Often native speakers have little or no training in the formal aspects of language, while they have spent copious amounts of time on the theory and methodology. They often know how to teach, but not really what to teach.”

Many seasoned NNESTs point out that they can have greater empathy toward their students because they themselves have had to learn English and can recognize the specific difficulties their students can face. This is particularly the case with non-native ESL teachers teaching in their home countries. Stella Tsali, educator and ESL teacher at a private school in Athens, Greece, explains, “I have no doubt in my mind that an NNEST is by far superior to an NEST, the only exception being if the NEST has lived in Greece and immersed themselves in Greek culture […].” Additionally, the status of being a native English speaker is no guarantee of in-depth language knowledge. “Studying English for a teaching career in Greece, and perhaps in other countries, requires a lot of training in the particularities of the language, as well as its theoretical concepts, which pertain to linguistics, pragmatics etc. […] Often native speakers have little or no training in the formal aspects of language, while they have spent copious amounts of time on the theory and methodology. They often know how to teach, but not really what to teach,” Tsali says.

Figure 4: Survey to native English-speaking teachers.

Figure 5: Survey to native English-speaking teachers.

Figure 6: Survey to non-native English-speaking teachers.

Figure 7: Survey to non-native English-speaking teachers.

Does the market really prefer NESTs?

The ESL market was worth $33.5 billion in 2018, and that figure is expected to grow to $54.8 billion by 2025. With a maximum of 400 million native speakers of English around the world and between 1.5 and 2 billion people who speak English as a second or other language, it is a big business, and many schools explain their preference for hiring natives as being driven by market pressures and demands.

“We are a medium-sized language school […] which opened in 2010. There are a lot of language schools in Tarragona, so it is a very competitive market,” Tim Bowring, a language school owner in Tarragona, Spain, told BridgeUniverse. “We aim to offer a high-quality service at a reasonable price. Up until now, we have only employed native speakers because this is what our customers want. Parents always ask where the teacher is from because they want their child to have a native-speaking teacher. This is one of our USPs, as lots of our competitors employ non-native teachers.” A further requirement for Bowring is that teachers can legally work in Spain, which means they must hold a European Union passport. He does highlight, however, that experience and qualifications are the essential factors and that NNESTs have some potential benefits over NESTs. “We advertise for experienced, qualified, and dedicated teachers with native-level English skills. However, one potential benefit of hiring a non-native speaker could be their ability to understand the student’s language-learning journey better.”

“In all the sectors of education I’ve worked across in the Latin American region, we have had a strong preference for native-speakers. The number one reason for this is client preference…”

In Latin America, the preference for native-speaking teachers is also market-driven, as Guy Courchesne, Managing Director of recruitment agency Teachers of Latin America S.C., explains. “In all the sectors of education I’ve worked across in the Latin American region, we have had a strong preference for native-speakers. The number one reason for this is client preference, be they students and parents of students in ESL classes or schools that seek our services as a recruitment agent. In a nutshell, I try to provide what my client wants,” he says.

Despite these clear market preferences, however, anti-Native Speakerism advocates point out that just because the market prefers it does not mean the market should get what it demands. “This could be a precedent to authorize pedagogical practices and promises that do not have any theoretical basis (except the beliefs of the layman), to please clients, or reinforce biases related not only to countries of origin but also age, race, and sexual orientation of teachers because that is what students ‘prefer.’ This would then be the institutionalization of prejudice over effectiveness for the sake of customer satisfaction,” says Vinicius Nobre, teacher and managing partner at educational consulting company Troika, in São Paulo, Brazil. Put even more directly by Dr. Adrian Holliday, Professor of Applied Linguistics & Intercultural Education at Canterbury Christchurch University, when responding to questions from BridgeUniverse, “racism, or selling racist products, cannot be justified because ‘the customer wants it.’ The so-called ‘native-speaker’ teacher is, quite simply, a racist product.”

Who is included in the native-speaker definition?

In some countries, including China, there are limits on who can be granted a visa to teach English as a second or other language. The criteria for receiving a visa can include being a native English speaker, and this is usually considered to be proven by nationality.

This brings up the issue of whom we consider to be included in the definition of the native speaker. Do we stick to the Western-centric, and potentially racist, view of including only those from Britain, the US, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa (Kachru’s so-called inner circle of English-speaking countries) or do native speakers also come from Nigeria, India, Singapore, and English-speaking Caribbean nations (Kachru’s so-called outer circle)? As demonstrated by an anecdote provided by one of the US respondents to the Bridge Native Speakerism survey, who is working as a teacher in Chile, race can be another roadblock to being viewed as a native speaker. “When my supervisor met me for the first time, he told me he was surprised I was one of the teachers from the USA because I was not white,” the respondent says.

Caribbean ESL teachers often fall victim to discriminatory hiring practices that view them as “less than native.” Trinidadian prospective ESL teacher Arielle Sarran told BridgeUniverse that she often asks recruiters how their organizations or schools define “native speaker.” “I do this to know if I have a fair chance in the application process or if I would be wasting my time applying through posts that claim they want ‘Native Speakers.’[…] I ask that question with these job postings as I would like to know the category that I would be classed in, being a Trinidadian.”

This issue is further compounded in the industry by the people who are often chosen as experts and ESL gurus, in the opinion of Dr. Renee Figuera, founder of Action TESOL Caribbean, an organization advocating for Caribbean ESL teachers. “Many [TESOL] conferences and professional development circuits/entities have promoted Anglo-centric culture from larger, English-official countries, from the inception. ‘Black Lives Matter’ has raised sensitivities to the need for diversity,” she says, regarding who represents expertise in the industry.

In some regions, discrimination is even more explicit, as Tiffani of Future Recruiting, a company based in the US but which mainly specializes in hiring ESL teachers for Asian markets told BridgeUniverse. “We have been told unqualified [teachers] were Black teachers, South Africans, teachers from Iran, teachers of a certain age, appearance […] primarily teachers of a darker skin tone were mostly discriminated against, and then those who did not speak English as a first language. Also, Asian descendants who were born outside Asia but sought employment [there] were considered locals by schools, even though [they] were born outside Asia. The schools didn’t want to employ them.” Since it opened in 2011, the agency has focused on educating the market to hire the best candidates, regardless of race, nationality, or other discriminatory characteristics. “Our approach is that if we educate parents that talent and skills do not have color or nationality, they’ll be inclined to find the best educator for [their] child. We are not a company that partners with any school that discriminates,” Tiffani said.

Academic perspectives: beyond the NEST v NNEST dichotomy

The aim of learning English perhaps used to be to become as proficient and communicate as much like a native speaker as possible, but as the status of English has grown as an international language, this premise is now being questioned. As Tomasz Paciorkowski, a PhD student at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland told BridgeUniverse, “I would argue that we should choose our teachers based on criteria different than nationality and native language. We should ask ourselves questions like, Why am I learning the language? Do I want to pass any exams? Does the teacher I am considering have appropriate qualifications? Am I learning the language to live in a given English-speaking country or will I mostly communicate with other non-native speakers?”

The reality is that most interactions in English around the globe are now between two or more non-native speakers. Academics like Tomasz Paciorkowski and Dr. Adrian Holliday, who was the first to use the term Native Speakerism, argue that the native speaker ideal, or native speaker fallacy, becomes redundant in the age of international English. Even using the terms NEST and NNEST reinforces the belief that there is a difference and distinction between these supposed categories of teachers.

“I actually want to abolish the native-non-native-speaker distinction because I think that it’s false and racist because it’s based on the idea that so-labeled ‘native speakers’ are culturally superior because they come from the West.”

As Holliday told BridgeUniverse, “I actually want to abolish the native-non-native-speaker distinction because I think that it’s false and racist because it’s based on the idea that so-labeled ‘native speakers’ are culturally superior because they come from the West. I think that using these acronyms strengthens the false notion of native-non-native-speaker difference. […] It certainly doesn’t help at all when researchers try to compare the merits of so-labeled ‘native speakers’ and ‘non-native speakers’ as if they really exist. Any suggestion that people who are labeled one or the other are better or worse at anything is just another form of racism. However, there is justification for people who are labeled ‘non-native speakers’ forming political groups of resistance — fighting discrimination. […] They need to fight to abolish the labeling rather than to prove that so-labeled ‘non-native speakers’ have different attributes to so-labeled ‘native speakers.’”

Moving toward a blended approach

If there are any conclusions to be drawn at all from BridgeUniverse’s investigation into Native Speakerism in the ESL industry, it is that quality, qualifications, and experience should be the criteria for hiring any ESL teacher. While there are still many schools that exclusively hire so-called native speakers and that debate rages on, progress is quietly being made in some corners of the globe toward an approach that blends both NESTs and NNESTs, if we are even permitted to make the distinction.

“We do not hold with any strange ideas that native English speakers are better or that non-native speakers are worse,” Tim Child, Director of Little Britain Language Services language school in Budapest, Hungary, told BridgeUniverse, adding that he hires a mixture of native English speakers and Hungarian speakers. “When we started the company, [we] decided that we should stand for quality and we should only employ teachers with at least a BA, and if they were not native English speakers, they need to have spent a year or more in a native-speaking country. […] We also decided teachers should have a quality teaching qualification. […] This policy stands for quality and perhaps it is our selling point, but more importantly, we have learned that it’s the best way to go. Teaching quality is very important and for us, the right teacher is best.”

Bridge is dedicated to empowering a global community of English teachers. Learn more by visiting us at bridge.edu.

Like this project

Posted Apr 24, 2024

Native speakerism is a controversial issue widely discussed in the ELT industry. However, is it discriminatory practice or a response to market demands? We inv…